Free Society of Traders

Essay

The Free Society of Traders, a joint-stock company founded by a small group of English Quakers in 1681, was organized with the intention of directing and dominating the economic life of colonial Pennsylvania. But, from the beginning, controversy about the Society’s existence revealed fundamental political divisions within William Penn’s “Holy Experiment,” and opposition led to the Society’s early demise.

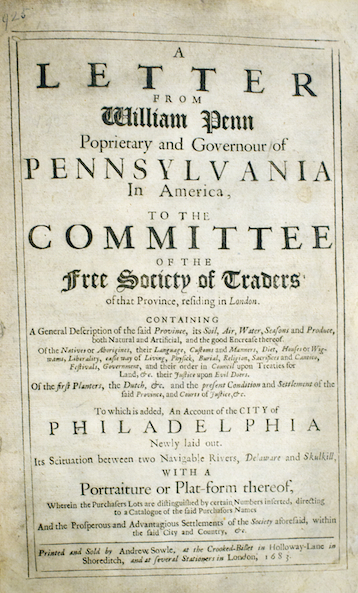

An experienced colonial promoter, William Penn (1644-1718) recognized that the success of his colony rested not only on a healthy supply of emigrants but also on a steady infusion of financial capital. Penn convinced many successful merchants and wealthy gentry that Pennsylvania was a place of both religious freedom and limitless economic opportunities. Connecting with the urban centers of English Quakerism–Dublin, Cork, Bristol, and London–Penn drew in many of these men to become the “First Purchasers” of land in the fledgling colony and to provide financial backing. In order to ensure their continued support and much-needed capital, Penn encouraged the creation of what became the Free Society of Traders, a company of elite merchants, landowners, and personal associates who were granted special concessions in order to direct the economy of the young colony.

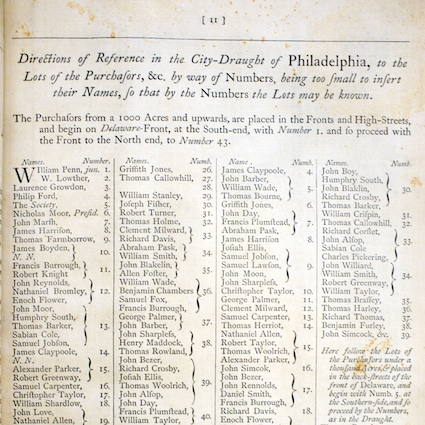

This privileged position was evident in Penn’s March 1682 charter for the Free Society, which granted the company and its members 20,000 acres of land and the promise of three seats on the Provincial Council in Philadelphia. Led by Dr. Nicholas More (?-1689) and James Claypoole (1634-87), the Society laid out an ambitious plan that would take advantage of resources such as agricultural fields, mining operations, fisheries, a fur trade with regional Indian tribes, and manufactories in Philadelphia, on the Delaware River, or on the Chesapeake Bay.

The Society failed to realize its founders’ ambitions, however. Crippled by disinterested officers and outmaneuvered by independent merchants, it suffered credit and money woes within a year of its founding. Even with its financial status in turmoil, a larger problem arose over the political concessions that Penn granted the company as Swedish, Dutch, and English settlers already residing in the colony and newly arrived entrepreneurs objected to the Society’s privileged status. As general dissatisfaction with Penn’s proprietary politics grew, the Society faced even more opposition, including the Pennsylvania Assembly’s refusal to confirm the company’s charter in December 1682. Further financial crises and a spate of lawsuits reduced the Society to little more than a land company. By 1686, it was forced to sell its extensive property to pay off debts. Still, the members of the Society remained prominent people in early Philadelphia, frequently occupying positions of executive and judicial importance even after the company was dissolved in 1723. Ultimately, the Society’s demise was symptomatic of the political scene in early Pennsylvania, as newer colonists sought to move the region away from control by Penn and his closest allies to a society directed and governed by the people themselves.

The legacy of the Free Society of Traders and its members is preserved by the neighborhood where its trading house and much of its property once stood, Society Hill. Extending roughly from Walnut to Lombard Street and from Front to Fifth Street and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971, Society Hill preserves much of the architectural heritage of colonial Philadelphia.

Lance R. Eisenhower is a Lecturer of History at Montgomery County Community College. He holds an M.A. in history from Villanova University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University.