Pontiac’s War and the Paxton Boys

Essay

Pontiac’s War (1763-66), a conflict between Native Americans and the British Empire, began in the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley regions but had important ramifications for Philadelphians as panic in the Pennsylvania backcountry sent refugees to the city. The arrival of the “Paxton Boys,” who were determined to seek revenge against Indians, sparked a political crisis with lasting consequences.

The immediate catalyst for the war was the French surrender of its North American territories at the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763, which left Native peoples bereft of an important ally with which to check British imperial claims on their lands. Historians in the past referred to the war as an “uprising,” but the term is misleading. An uprising implies rebellion against an established authority; most Indians involved in the conflict were far beyond British imperial control. Pontiac (c. 1720-69), the Ottawa warrior whom the war is named after, was only one among many Indian leaders coordinating attacks on British forts and settlers. Pontiac’s treaty with the British at Fort Ontario in 1766 ended his part in the war, but Indians east of the Mississippi continued to fight British, then American expansionism in the decades that followed.

Initially, the war appeared to be far removed from eastern Pennsylvania. The conflict began in the spring of 1763 when Pontiac assaulted Fort Detroit with Ottawa, Huron, Pottawatomi, and Ojibwa warriors. Pontiac failed to take the fort, but his siege cut Detroit off from vital British supply and communication lines. Within a few months, Native groups succeeded in overtaking at least eight other British outposts in the Great Lakes and Ohio Country regions. Fort Pitt remained in British hands, but Lenape (Delaware), Shawnees, and Mingos successfully besieged it for months and harassed its supply lines.

Pontiac’s “Savage Genius”

The nineteenth-century historian Francis Parkman (1823-93) believed Pontiac was the mastermind behind the war who united disparate Indian groups, but in reality his influence was limited. Native groups coordinated their attacks, but each Indian community fought to preserve its own autonomy. Besides a common enemy, Indian combatants were also linked together by a network of Native religious revivalism that rejected dependence on European trade goods–alcohol was particularly singled out–as a way to keep Indian and white colonists separate. For Indian participants, Pontiac’s War had religious as well as political dimensions.

Indian raids threw backcountry Pennsylvania settlers into sheer panic. Lenape and Shawnee warriors in small raiding parties of a dozen or more attacked frontier farms and settlements as far east as the Susquehanna River Valley. There are no firm casualty figures, but in addition to the perhaps hundreds of colonists killed or captured, thousands of frontier settlers fled to Philadelphia and to more secure towns and fortifications in the Delaware Valley. Hastily organized militia companies were ineffective at preventing the raids, and Lt. Governor James Hamilton’s (c. 1710-83) £25-per-head scalp bounty accomplished nothing except to encourage armed colonists to bully or kill a few neighboring Indians who had nothing to do with the conflict.

In November 1763, the threat of settler violence motivated hundreds of Moravian Indian converts from Bethlehem to relocate to Philadelphia seeking the provincial government’s protection. They were soon joined by other Indians from Wyalusing, a mixed-Native settlement in the upper Susquehanna. The government housed the Indians in a city-owned infirmary on Province Island (in the Delaware River south of Philadelphia).

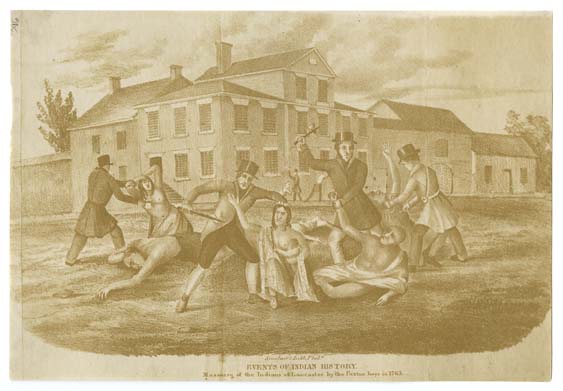

Conestoga Indians Slain

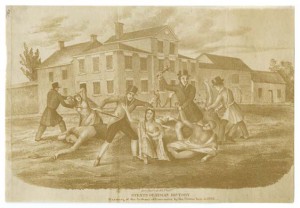

While on Province Island, the refugees suffered from disease and neglect, but a far worse fate awaited the small community at Conestoga, an Indian reserve near Lancaster that was supposed to be under the protection of the Penn family. In December, approximately fifty Scots-Irish Presbyterian settlers from Paxton Township rode into Conestoga and massacred six inhabitants, mutilating and scalping their bodies. The “Paxton Boys,” as the vigilantes came to be known, claimed the unarmed Conestogas were harboring enemy spies and providing material support to the Indian war effort. The charge was a fabrication that masqueraded as a justification for the killings. In reality, the Paxton Boys’ were eager to rid the Susquehanna Valley of all Indians, friendly or combatant. The remaining members of Conestoga sought protection inside a Lancaster workhouse, but the Paxton vigilantes arrived a week later and forced their way in, massacring another fourteen. A company of Royal Highlanders stationed nearby did nothing to prevent the atrocity, and the attackers were never brought to justice.

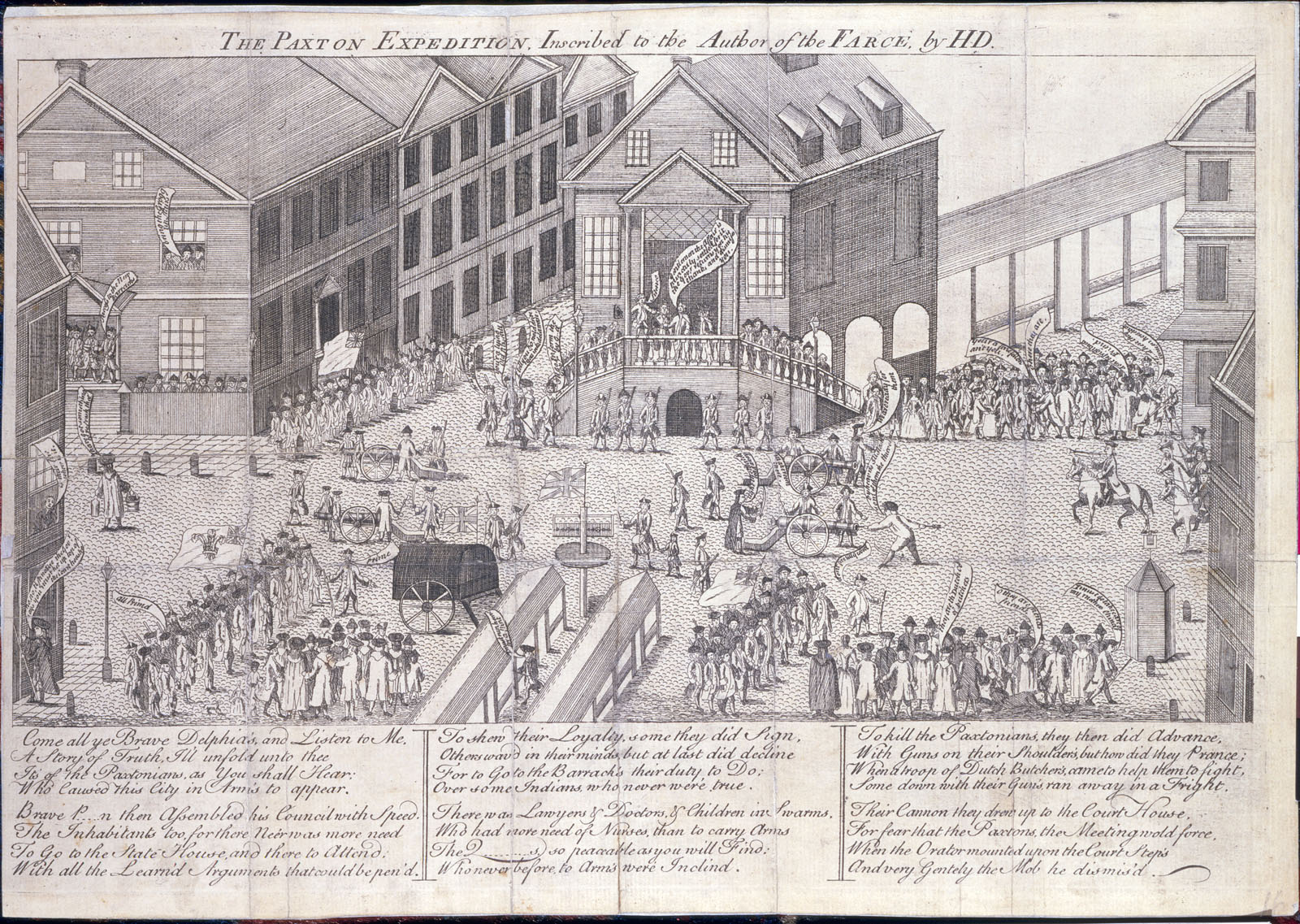

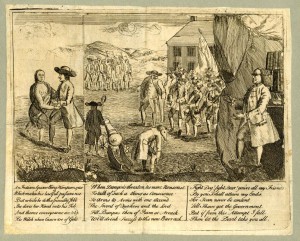

In January 1764, as many as two hundred settlers from Paxton marched to Philadelphia, making it as far as Germantown, where they decided to halt after hearing that the city’s militia had mobilized. The marchers claimed they were merely protesting the government’s failure to protect them. It is doubtful whether anyone believed their second stated intention to “conduct” the Indian refugees at Province Island out of the colony without harming them. Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) negotiated a compromise: The marchers agreed to disperse, and one of the leaders, Matthew Smith (1734-94), was allowed into the city to publish their grievances.

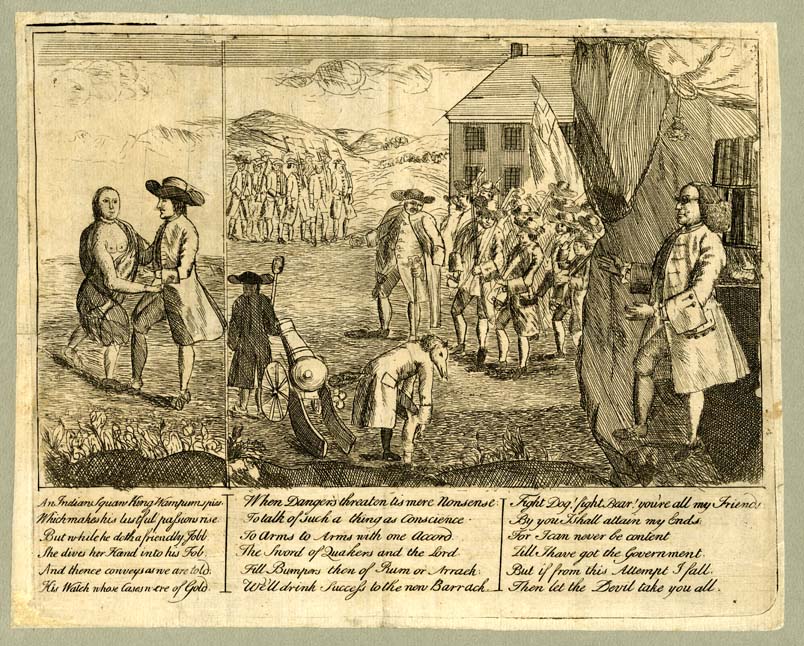

The crisis marked a major turning point in Philadelphia’s history. It ignited a tract war that pitted Benjamin Franklin and the “Quaker party” in the Assembly against backcountry settlers and their supporters in Philadelphia. The latter group depicted the city’s Quaker elite as hypocrites who cared more for the welfare of Indians than for frontier settlers. One political cartoon depicted Quakers and Indians riding on the backs of Irish and German colonists; another showed the prominent Quaker leader Israel Pemberton (1715-79) dancing with a topless female “squaw.” Franklin tried to reframe the debate by blaming the colony’s problems on the newly-arrived proprietor John Penn, but he badly miscalculated by advocating that Pennsylvania be turned into a royal colony–a proposition that, not surprisingly, went nowhere on the eve of the Stamp Act crisis. The elections held later that year, which saw the highest voter turnout up to that time in Pennsylvania’s history, swept Franklin and members of the pro-Quaker party out of the Assembly and inaugurated a new era of popular politics. The anti-Indian racism epitomized by the Paxton Boys also endured well beyond the American Revolution.

Michael Goode is an Assistant Professor of Early American History at Utah Valley University.

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University.