Indian Rights Associations

Essay

The Women’s National Indian Association and the Indian Rights Association, both founded in Philadelphia in the late nineteenth century, led the way in setting a national agenda concerning the plight of Native Americans. They continued a local tradition of reform movements promoting rights and freedom.

Founded in 1879, the Women’s National Indian Association organized by Mary Lucinda Bonney and Amelia Stone Quinton of the Home Mission Circle of the First Baptist Church of Philadelphia became nationally prominent. During the association’s first three years, it merged and renamed itself often as it collaborated with other Protestant groups in the Northeast and Midwest who shared its missionary zeal and desire to ensure that Indians had their political rights on reservations protected.

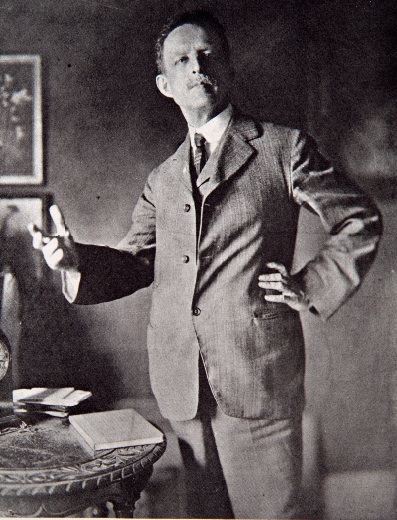

While the women’s group focused primarily on religious matters, on December 15, 1882, thirty or forty wealthy reform-minded gentlemen gathered at the Philadelphia home of the Honorable John Welsh to hear from the judge’s sons, Herbert (1851-1941), and Henry S. Pancoast (1875-1939). They had just returned from a visit to the Dakota Territory as guests of Episcopal missionary Bishop William Hobart Hare (1838-1909). Concerned about the living conditions of the Sioux and U.S. Indian Bureau corruption, the men created the Indian Rights Association (IRA).

Over the next 100 years, the IRA worked “to secure to the Indians of the United States the political and civil rights already guaranteed to them by treaty and statutes of the United States.” Members concentrated on education, enforcement of state and territory law on reservations, and the establishment of a system of individual land ownership on reservations. IRA members believed assimilation and Americanization within a Protestant context were the way for Indians to survive in the fast-growing United States.

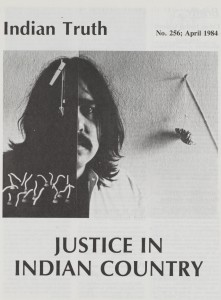

The IRA’s strength and longevity came largely from a strategy focused on popular opinion and federal legislation. Within two years of its founding, the IRA established a second office in Washington, D.C., and within three years had chapters nationally. Use of the press and lobbyists allowed the IRA leadership to affect federal appointments and introduce bills such as the Citizenship Act of 1924, which granted U.S. citizenship to all Indians. The IRA investigated tribal complaints about federal agencies, filed amicus briefs on Indian issues, and supported tribes in property conflicts and tribal recognition. Its Indian Truth, published from 1924 to 1986, promised, in its editor’s words, “a brief comprehensive review of Indian happenings”— from social news to legal proceedings and summaries of educational programs.

Due to this publication and an active speaker circuit, the IRA became one of the primary sources of information and documentation of life on Indian reservations. By the mid-1900s, IRA’s mission changed from educating Indians in the ways of the “white” world to educating mainstream Americans about native cultures. In 1971, the board of directors officially recognized a shift in its mission with new policies.

By the time of its centennial in 1982, the IRA found it necessary to reconsider not only its mission but its purpose for being. Indian-run organizations were performing many of the functions that it had. Unable to develop a unique niche and find funding, the IRA closed its doors in 1994.

Beth A. Twiss Houting is the Senior Director of Programs and Services at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. She holds a B.A. in History from Pennsylvania State University and an M.A. from the University of Delaware in the Winterthur Program in Early American Culture with a Certificate in Museum Studies. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University