Columbia Avenue Riot

By Alex Elkins

Essay

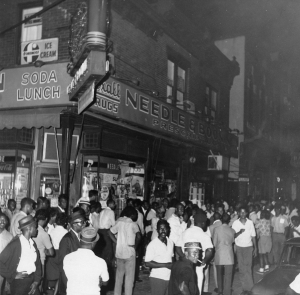

On Friday, August 28, 1964, a scuffle with police at the busy intersection of Twenty-Second Street and Columbia Avenue sparked a three-day riot involving hundreds of North Philadelphians hurling bottles and bricks at police and looting stores. With the Columbia Avenue Riot, Philadelphia joined six other cities, including Jersey City, Paterson, and Elizabeth, New Jersey, that erupted in African American protest during July and August 1964. Similar actions in hundreds of other cities followed by 1968. In Philadelphia, as across the country, urban unrest fractured liberal interracial coalitions and gave rise to law-and-order politics.

At 9:20 on that August night in 1964, two Philadelphia police officers ordered a married couple to move their car from the intersection at Twenty-Second and Columbia Avenue (the street later renamed for civil rights leader Cecil B. Moore). The ensuing scuffle touched off a rumor that the police had beaten and possibly killed a pregnant African American woman. Rioting spread through an area of North Philadelphia that the local press and the police establishment since the mid-1950s had designated “the Jungle” for its entrenched poverty and high crime rates. Like other “ghettos,” the area of Poplar, Lehigh, Tenth, and Thirty-Third Streets also was racially segregated; by 1960, it was 69 percent African American.

The riot reflected longstanding popular anger at the Philadelphia Police Department and growing divisions among African Americans over a recent shift to more confrontational street protests. On the first night, crowds of young men and women ran along Columbia Avenue, smashing the windows and taking the merchandise almost exclusively from white-owned stores. The busy commercial strip in the heart of North Philadelphia was lined with taprooms and small shops, the vast majority owned by Jewish merchants who sold groceries, appliances, and furniture. One group tossed a garbage can through a squad car window. Crowds pulled prisoners out of police wagons. An activist with the National Muslim Improvement Association led chants of “We want freedom, we want justice!” Directing the crowd’s anger at Cecil B. Moore (1915-79) for failing to deliver promised reforms despite militant mass protests, one local resident declared, “We don’t need Cecil Moore. We can take care of ourselves.” Members of the crowd also turned their anger on more moderate civil rights leaders who, like Moore, tried to restore calm.

1,800 Police Converge

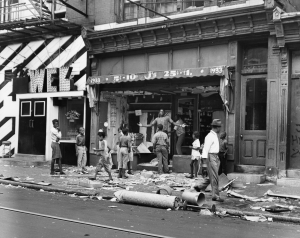

By the second and third nights, police presence swelled to 1,800 officers. Commissioner Howard Leary (1912-94) instructed police to use minimal force. On Saturday, Mayor James H. J. Tate (1910-83) imposed a curfew in the riot area. By Monday morning, the Columbia Avenue Riot was over. Hundreds had been arrested and injured, and two died. Seven hundred twenty-six buildings had been affected. Property damage and police overtime pay totaled $3.2 million.

In the next few years, the civil rights movement embraced racial militancy and distanced itself from former white allies. Protests increasingly confronted a police force, led by then-Deputy Commissioner Frank J. Rizzo (1920-91), which proudly embraced racial partisanship. After the uprising, the Fraternal Order of Police escalated its campaign against the civilian-led Police Advisory Board. The Police Department countered the rise of Black Power with a siege mentality that treated Black protest as a threat to the city. By 1969, the Police Advisory Board was gone. Three years later, Rizzo was mayor.

Many local businesses never recovered from the August 1964 uprising. Although the flight of white residents and industrial jobs played a greater role in long-term neighborhood decline, the Columbia Avenue Riot accelerated these trends and contributed to the sense already possessed by Rizzo and many white Philadelphians that “the Jungle” was a violent place to be contained by force. Still, the unrest generated key momentum for local activists that arguably culminated in the election of the city’s first African American mayor, Wilson Goode (b. 1938), in 1983.

Alex Elkins is a Ph.D. Candidate at Temple University, writing a dissertation on the 1960s riots and “get-tough” policing. His article, “‘At Once Judge, Jury, and Executioner’: Rioting and Policing in Philadelphia, 1838-1964,” appears in the Spring 2014 issue of the Bulletin of the German Historical Institute. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Lesson Plan: Columbia Avenue Riots, 1964 (Temple University)

- Columbia Ave Riots: Lynne Abraham (Philadelphia: The Great Experience)

- Columbia Ave Riot: Sonny Driver (Philadelphia: The Great Experiment)

- Ruminating On Lost Columbia Avenue (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- When Columbia Avenue Erupted (Hidden City Philadelphia)

National History Day Resources

- Night Footage of Columbia Avenue Riots (Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives)

- Columbia Avenue Riots: Correspondence (Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives)

- Report of 1964 September 18, United States Department of Justice (Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries)

- “Case Study of a Riot: The Philadelphia Story,” Institute of Human Relations Press, 1966 (Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries)