Maps and Mapmaking

Essay

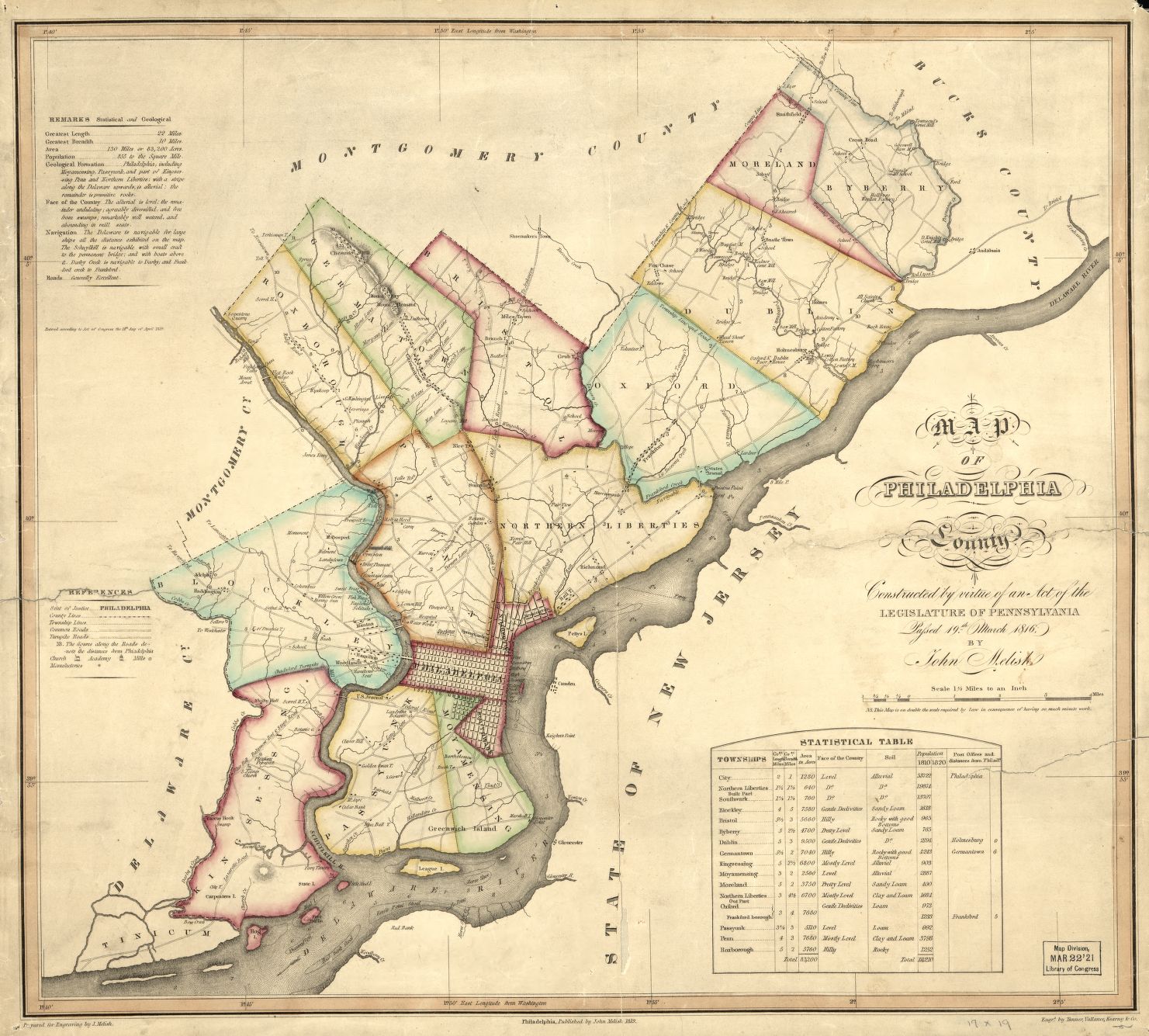

As the country’s largest city, and for a time capital of the new nation, Philadelphia was well situated to chart the young republic’s changing geography. Using its capacity to attract all the manufacturing elements necessary for successful publishing—printers binders, colorists, engravers and others—Philadelphia became the home of the nation’s first full-time geographical publisher and soon became the center of the American map publishing industry.

In the early years, the major market for cartographic products centered on geographies, general atlases, and gazetteers that served the republic’s increasing appetite for maps. Map publishing in Philadelphia began with Mathew Carey (1760-1839), who had already published several periodicals. His initial venture centered on his plans in 1792 for publishing an American edition of Guthrie’s Geography (1786) with maps as illustrations. In 1795, he issued the first edition of Carey’s American Atlas, which contained some of the first depictions of the individual states of the union. Carey was a general publisher; maps were not his primary product. However, he led the way in using the “cottage industry” of individuals and small firms found throughout Philadelphia to provide needed services.

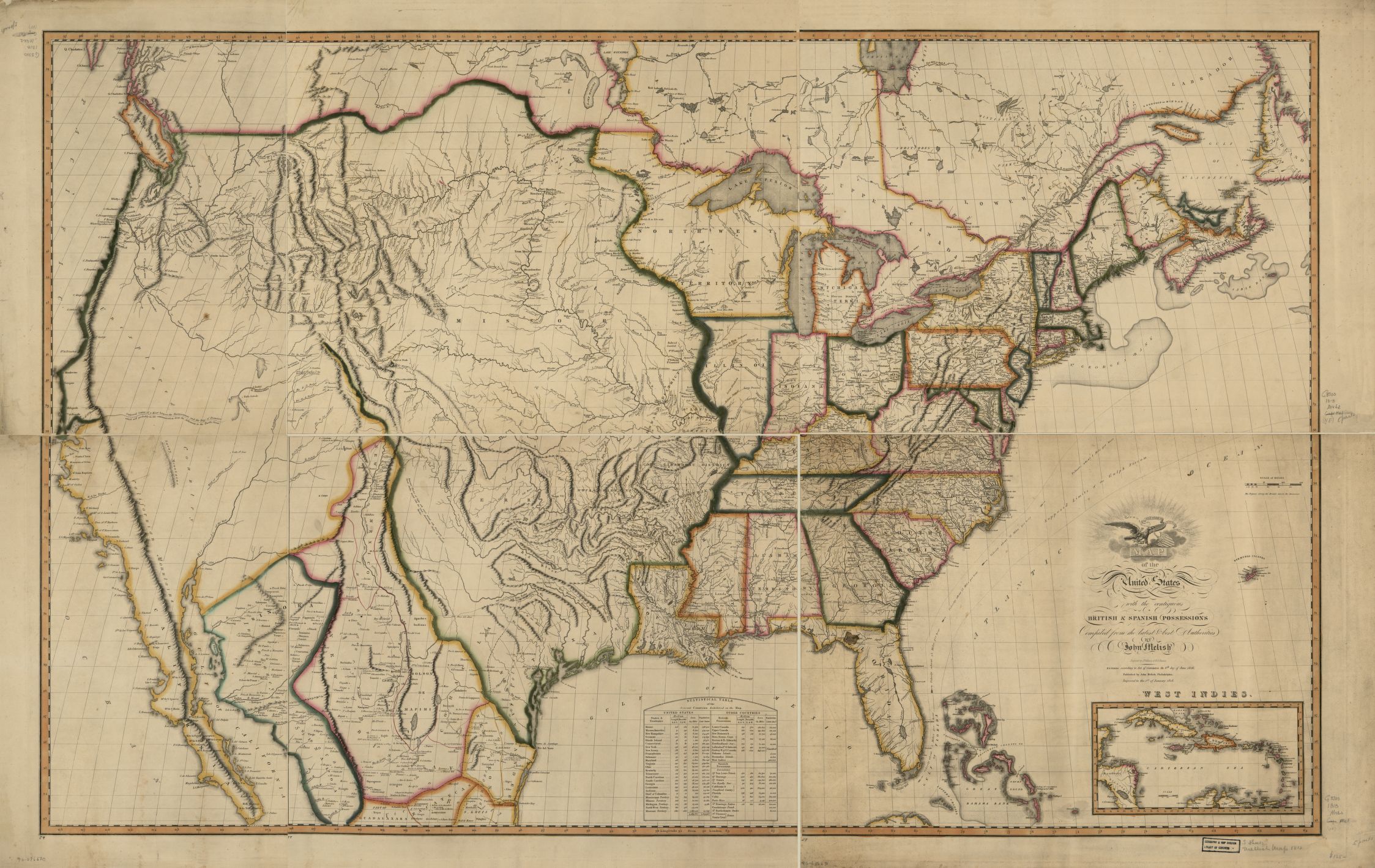

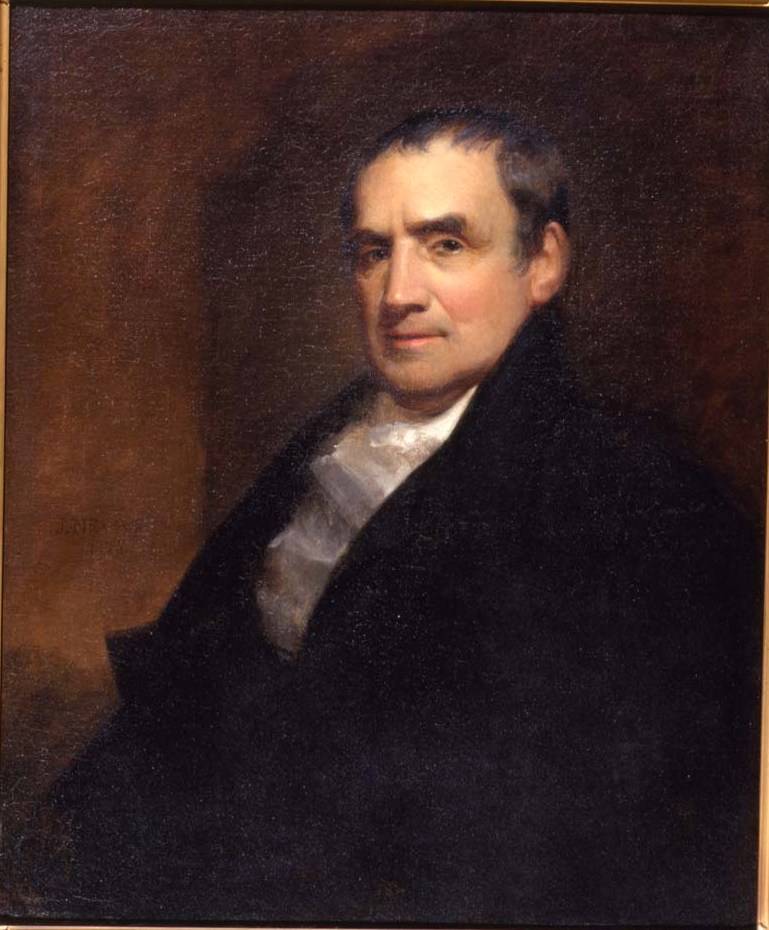

Carey’s domination of Philadelphia publishing during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries did not prevent others from relocating to take advantage of the commercial opportunities found within the city. The nation’s first full-time geographical publisher, John Melish (1771-1822), a native of Scotland, settled in Philadelphia in 1811 after many travels around his new country. Melish has been considered one of the founders of the American commercial map trade.

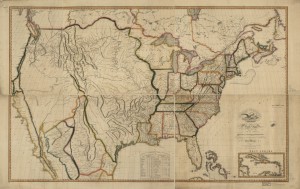

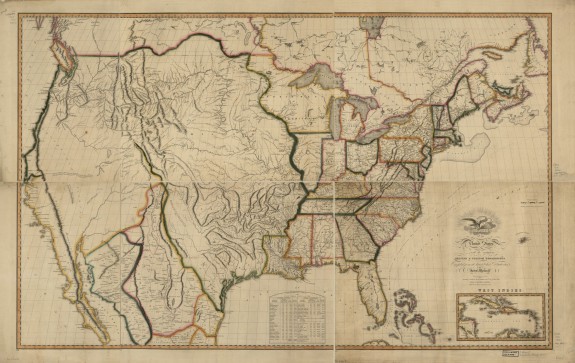

Melish assumed the mantle of America’s premier map publisher and geographer from Carey after the publication of his Map of the United States. This ranked as a significant and influential milestone in American cartography. Recognizing the curiosity of Americans about their own country especially after the War of 1812, he furnished a large-scale map of the entire United States as well as all of the North American British and Spanish possessions that bordered America. This map, which first appeared in 1816, became an invaluable tool in determining boundaries, which were still in flux between the United States and its neighbors, including Florida, Mexico, and Canada. The 1818 edition of the map was used for delineating the boundaries between the United States and Spain and was specifically mentioned in the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819. For the first time, it gave Americans a view of the vastness of a country augmented by the Northwest Ordinance and the Louisiana Purchase.

Magnet for Talent

Carey’s and Melish’s contemporary presence in Philadelphia drew significant talent to the city in the fields of cartographic engraving and printing. Chief among this talent was Benjamin Tanner (1775-1848), who relocated his engraving business from New York to Philadelphia by 1805 and serviced both Carey and Melish. He was joined in Philadelphia by his younger brother, Henry Schenck Tanner (1786-1858), by 1810. The younger Tanner worked principally with Melish. Melish’s death in 1822 cleared the way for Henry S. Tanner to succeed him as the premier American map publisher.

Others soon migrated to the city to compete with Tanner. Samuel Augustus Mitchell (1792-1868) entered the Philadelphia cartographic scene with his 1831 edition of A New American Atlas. Mitchell’s maps and atlases covered the entire spectrum of map publishing: atlases, state maps, guidebooks, and special maps. Mitchell’s maps could be found throughout the country. His greatest contribution to American cartographic knowledge came from the many and various geographies compiled under his auspices.

By the 1830s, schools looked for current and well-illustrated geographies and primers as part of their educational programs. Mitchell recognized the need for these textbooks and in 1839 issued his first school geography and atlas. Reviews throughout the country of his work were favorable, and within a few years a Mitchell’s geography became standard in many classrooms, both secular and religious. Among his most popular titles were Mitchell’s School Geography, Mitchell’s Primary Geography, Mitchell’s Ancient Atlas, and Mitchell’s Ancient Geography. Many of these texts, first appearing between 1839 and 1845, underwent reprintings and revisions into the late nineteenth century. One biographer stated that the Mitchell company enjoyed an annual sale of over 400,000 copies of its works.

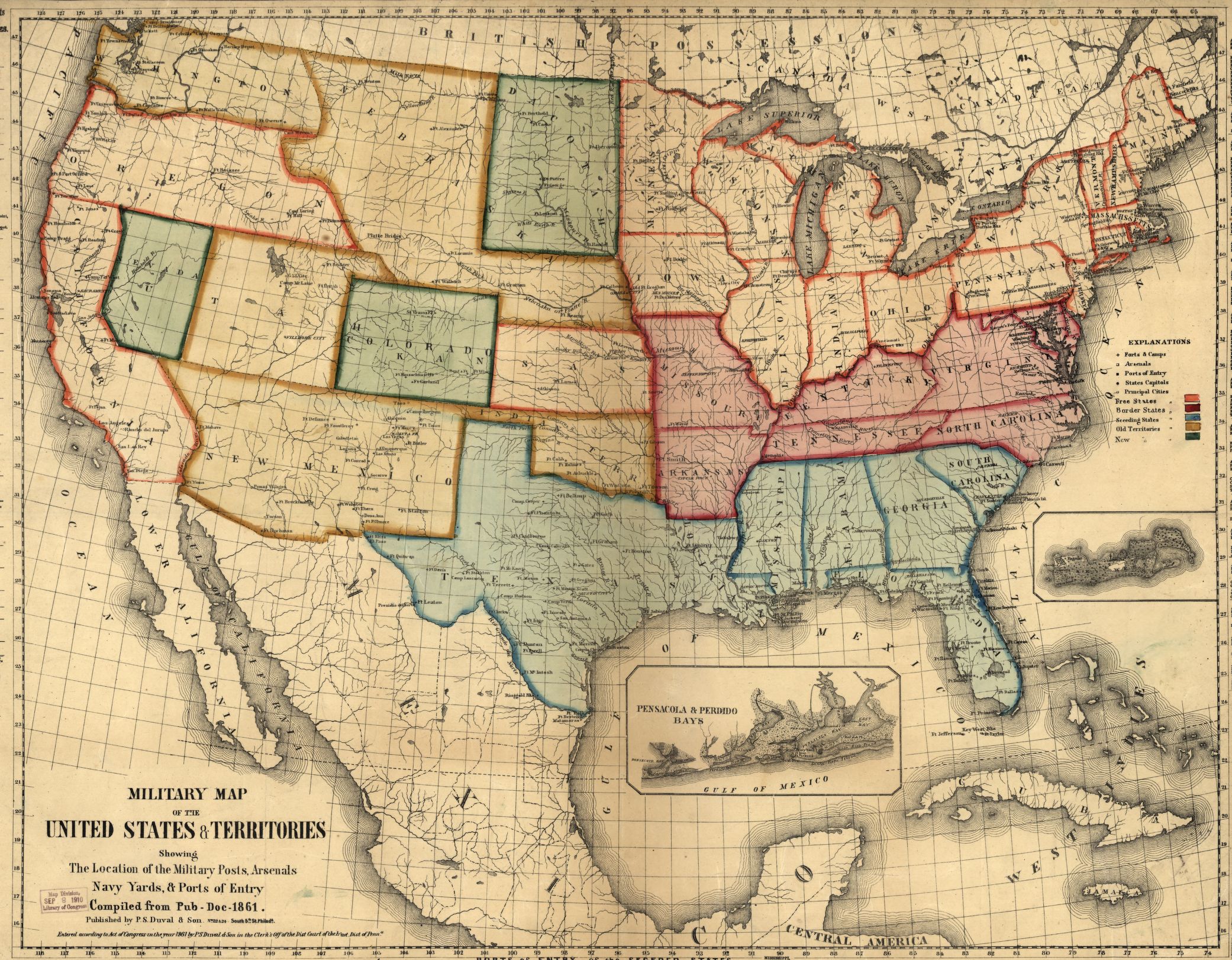

The introduction of the lithographic art into printing provided a cheaper form of reproduction for large as well as limited runs of maps. The first known lithographic map produced in the United States appeared in 1822, but no Philadelphia imprint appeared until 1830 when Cephas Childs (1793-1871) printed Plan of Land situate in Passyunk Township, Philadelphia County, Belonging to the Heirs of Henry Hill Esqr. Deceased. Childs hired Peter S. Duval (ca. 1804-86) in 1831 to run the lithographic shop, and Duval quickly rose to the top of the profession. Duval experimented in color lithography in the early 1840s and mastered the technique by early 1843. This innovation became crucial for the effectiveness of new forms of maps, including the cadastral (or land ownership) county map, the county atlas, and the fire insurance map.

The lithographic revolution spurred the cheap production of limited-run editions of maps. Maps now commonly appeared as appendixes to city directories; published briefs of title; annual reports of railroad, canal, and other transportation companies; auctions of property; and land development surveys. Publishers such as Mitchell still relied heavily upon the old copperplate engraving techniques, but this was cost effective only if there was a large publishing run.

More Than Just Maps

Maps were only a part of the lithographer’s business. Map publishers, however, continued to act as the managers of projects, raising the cash necessary for a successful production, engaging surveyors to conduct the surveys and consult official records, hiring lithographers and printers to engrave and print the product, and delivering the finished map.

Map publishers relied heavily upon subscriptions to finance their projects. A promoter would announce a project and seek subscribers to help underwrite the costs. These promoters or their agents would work with local newspapers to advertise their projects. Most counties had no detailed commercial maps prior to 1850, and local editors strongly urged residents of the area to support the various projects, often relying upon local pride to help the cause. The practice of allowing the speculator to become the “publisher” while requiring the address of the printer on the map might lead one to assume that dozens of publishers worked in Philadelphia. In truth, there were only a few; most of the county maps published in Philadelphia came from the Robert Pearsall Smith Map Manufactory. Between 1846 and 1864, Smith issued over 200 different maps that carried over 70 publishing names. A typical county map project, such as those for Mercer County, New Jersey (1849); Jefferson County, New York (1855); Adams County, Pennsylvania (1858); and Elkhart County, Indiana (1861), might last for over two years between the initial prospectus and surveys to the issuance of the completed map.

The large land ownership wall map reached its zenith in 1860-1861 with the Smith’s publication of Map of the Vicinity of Philadelphia by D. Jackson Lake and Silas Norman Beers. This map covered the region from Wilmington to above Trenton and measured about five- to six-feet- square. At least fifteen editions are known to exist, each with a different variation in the title and the inset plans.

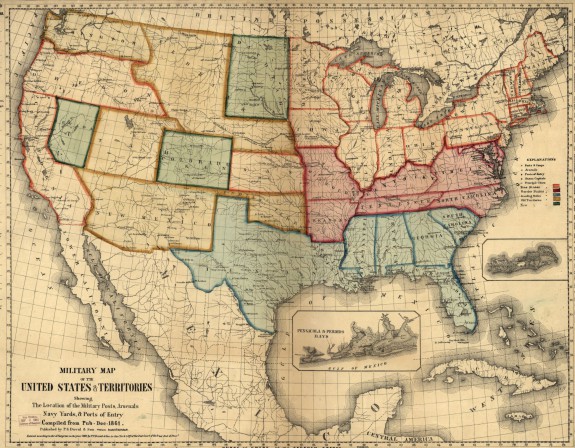

Current events and topical subjects provided much business for mapmakers. Mitchell and others were quick to issue maps of the Mexican-American War, Texas, and the Far West during the 1840s. The Civil War devastated the county map business as publishers changed their focus to meet new demands for mapping the war.

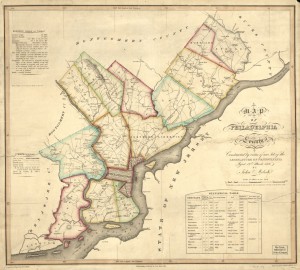

City Consolidation Mapped

Publishers did not ignore the potential of street and road maps of cities, states, and other geographical areas. City maps were often included in the general atlases, although some individual maps of Philadelphia occasionally appeared, both as separate items and as part of other publications, such as city directories. The consolidation of Philadelphia city and county in 1854 spurred the publication of several maps of the newly enlarged city, several of which were issued by Rufus L. Barnes (1794-1868), who had worked in map production since the early 1830s. Barnes also produced several large maps of Pennsylvania in the 1840s and 1850s. John L. Smith (1846-1921) assumed the business upon his retirement. The Barnes-Smith firm operated a retail store unlike many publishers.

Urban areas presented a unique and complex approach to map publishing. Unlike the county maps, in which roads and houses were few and scattered, the density of cities called for new methods of mapping. R.P. Smith created a prospective map of Philadelphia in 1849 that depicted lot lines, addresses, and building outlines but failed to garner the financial support necessary to carry the project any further. At the same time, George T. Hope created the first American fire insurance map (Maps of the City of New York), which appeared between 1852 and 1855. One of the contributors to this map was Ernest Hexamer (1827-1912), who moved to Philadelphia to create the Maps of the City of Philadelphia, which first appeared in 1857. Hexamer continued to supply fire insurance maps to Philadelphia until the firm was merged with the Sanborn Map Company of New York in 1915.

Following the Civil War, publishers seized upon a new format to rekindle the county map business to help satisfy the American need to celebrate its history before and during the Centennial. The Philadelphia map publisher Henry Frederick Bridgens (1825-72) converted his Map of Berks County, Pennsylvania (1860) into an atlas with the same title in 1861, thus giving birth to the county atlas. The growth of the county atlas started slowly owing to the disruptions of the Civil War. By 1866, only six county atlases had been published. With the war over, however, fifty-five additional titles appeared between 1866 and 1870 as the atlas replaced the map as the principal format for dispensing land ownership information in America. All but nine of the sixty-one titles that appeared in this period had New York or Philadelphia imprints.

Philadelphia’s position as the center of American map publishing was increasingly threatened not only by publishers in Boston and New York during the 1850s and 1860s, such as J. H. Colton, Henry F. Walling, and Frederick Beers, but also by new firms in Chicago and other Midwestern cities, including Rand, McNally & Company. Some of the Midwestern companies initially relied upon Philadelphia printers and lithographers for their technical work. Soon they transferred their business to local printers or, in the case of Rand McNally, chose to consolidate all facets of the business under one roof.

New Firms Despite Competition

Despite the increasing competition, the city continued to attract new firms. Starting in 1865, the G.M. Hopkins Company emerged as one of the mainstays in American urban cartography. Louis H. Everts (1836-1924) moved from the Midwest to Philadelphia to produce many county atlases and county histories during the 1870s. Ormando Wyllis Gray (1829-1912) relocated his map publishing operations from Boston in about 1871 and concentrated on more general map publishing.

Hopkins introduced the urban real estate atlas format with the Atlas of (the late borough of) Germantown in 1871. The urban atlas publishers included pertinent information important to real estate brokers, insurance companies, and railroads. As the form matured, the atlas type became standardized in that each street, property and building was carefully plotted with boundaries noted. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a number of Philadelphia map publishing firms concentrated on publishing real estate atlases.

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries marked a decline in Philadelphia’s influence on the American map publishing industry. William M. Bradley & Brother continued publishing many Mitchell imprints into the 1890s, but this series faded and with it went Philadelphia’s share of the general map and atlas business as Rand, McNally & Company of Chicago assumed the role of leader in this field. Much of the success of Rand McNally lay in new production methods revolving around wax engraving not embraced by the Philadelphia publishers and engravers. A survey of those map and chart publishers in Philadelphia listed in the 1906 city directory shows that most of them focused upon county and urban atlases and street maps.

Philadelphia map publishers continued their dominance over the American urban atlas throughout the first half of the twentieth century. They produced many atlases of American cities. These publishers often opened offices in other cities to coordinate their mapping activities there. The Depression had an adverse effect on urban atlas publishing similar to that of the Civil War on the county wall map. The deaths of the founders of the significant firms brought second-generation ownership without the marketing skills to maintain significant operations in a changing market. The 1930s and 1940s saw a consolidation of some map publishers and the removal from Philadelphia of others. Lewis L. Amsterdam (1899-1991) founded Franklin Survey Company in 1928 after spending time as a map salesman for other companies. During the twentieth century, the Franklin Survey Company, later renamed Franklin Maps, absorbed both the Hopkins and J.L. Smith companies. Located in King of Prussia since 1986, it continued the tradition of map publishing started by Mathew Carey in 1793.

Jefferson M. Moak is a professional archivist, historian, and genealogist. He has worked at the Map Collection of the Free Library of Philadelphia, the Philadelphia Historical Commission, the Philadelphia City Archives, and most recently as senior archivist at the National Archives at Philadelphia. He has undertaken extensive research into the architectural, cartographic, and neighborhood histories of Philadelphia, publishing several guides to Philadelphia research, including Atlases of Pennsylvania (1974), Philadelphia Mapmakers (1976), Philadelphia Street Name Changes (1995, 2000), and Architectural Research in Philadelphia (2001-2002). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Greater Philadelphia GeoHistory Network

- Philadelphia on Stone (Library Company of Philadelphia)

- Printmaking Processes: Lithography (YouTube)

- American Memory Map Collections (Library of Congress)

- David Rumsey Historical Map Collection

- Mapping the Sesquicentennial (PhillyHistory.org)

- Of Philadelphia Maps and Mapmakers (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- From Colonialism to Tourism: Maps in American Culture (Exhibit, Digital Public Library of America)