Schuylkill Navigation Company

Essay

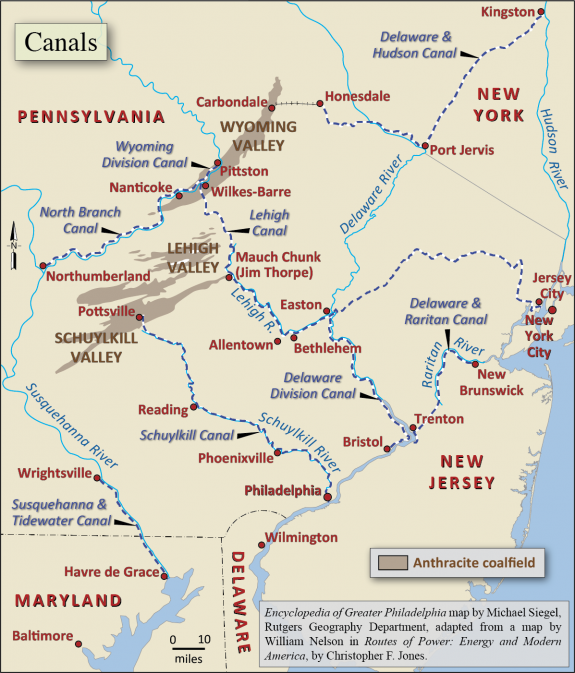

While eighteenth-century Philadelphians looked almost exclusively to the east and the Delaware River to connect them to the wider world, by the turn of the nineteenth century they looked increasingly to the Schuylkill River and the west. After several failed attempts to fund improvements that would make the rapid-filled Schuylkill River navigable in the 1780s and 1790s, in 1815 the Pennsylvania Legislature approved a charter for the Schuylkill Navigation Company to build a navigation system of canals, dams, and slackwater pools from Mill Creek, just north of Pottsville, along the river to Philadelphia. After an extension in 1828 to Port Carbon, Pennsylvania, the system’s reach to the anthracite coal region helped to accelerate Philadelphia’s industrial growth.

Enthusiasm ran high for the project from the start, but its managers faced a daunting task. Unlike the Erie Canal being built at the same time in New York, the Schuylkill system was not funded by the state; it was a private corporation. Moreover, though the navigation along the Schuylkill would be less than one-third the length of the Erie Canal (108.23 miles vs. 363 miles), the Schuylkill Navigation Company built 120 locks (as compared to 83 on the Erie Canal) and the first ever canal tunnel. Therefore, the success of the Schuylkill project depended on both technological and fiscal innovations.

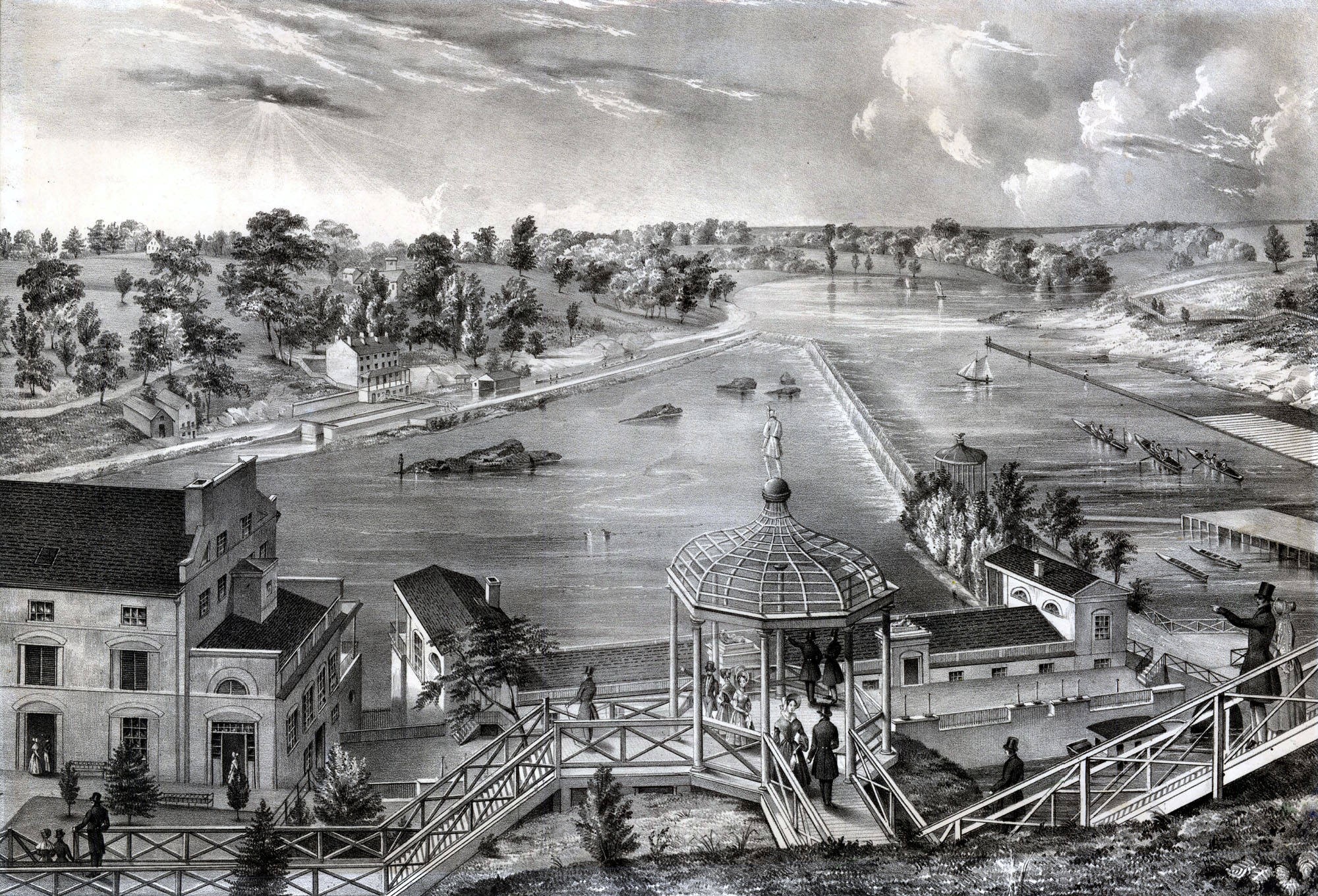

In order to begin work, the Schuylkill Navigation Company needed to find subscribers to purchase 10,000 shares to fund the improvement. Subscriptions were small investments, usually paid in three installments of less than ten dollars each. The company began work in 1816 but frequently ran out of money, forcing it to advertise for new subscriptions and plead to the state legislature. In 1823, the company took a mortgage loan from Philadelphia merchant-banker Stephen Girard (1750-1831) for $230,850, meaning that a default by the company would have given Girard ownership of the Schuylkill River. Technologically, the project also experienced difficulty finding reliable engineers, which forced repeated rebuilding of dams and locks. And legally, the Schuylkill Navigation Company faced opposition in 1819 from the City of Philadelphia’s Watering Committee, then planning the new Fairmount Water Works to improve water supply to the city. After a series of negotiations, the company and the Watering Committee agreed that the city would build and maintain the dam and lock system. The city also could use the water as long as the river was not drained below the top of the dam, which would prevent navigation.

Despite these frequent setbacks, including the death of principal engineer Thomas Oakes (1777-1823) in 1823, the stretch between Philadelphia’s Fairmount Water Works and Reading became navigable in 1824. The company celebrated with a ceremonial trip down the navigation on three inaugural barges, the Thomas Oakes, Stephen Girard, and DeWitt Clinton. An extension of the canal to Port Carbon, at the mouth of Mill Creek in Schuylkill County, completed in 1828, made the Schuylkill River Pennsylvania’s most efficient mode of transportation for anthracite coal for the following decade and a half. Despite its hefty cost of more than $2.3 million, the project became profitable from revenue gained primarily from tolls but also from rents on water power. In 1829, the Schuylkill Navigation Company began to pay dividends to its shareholders.

The Schuylkill Navigation Company’s monopoly on transportation to the rich coal lands in the region ended in 1842 with the opening of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad. Unlike canals, railroads did not freeze in the winter. Although they faced regular maintenance costs, railroads did not have to battle the same environmental challenges, like floods that often filled the canals with silt from the coalfields.

Faced with competition from the railroad, the Schuylkill Navigation Company enlarged the canal in 1846 to accommodate larger boats. Tonnage transported along the navigation increased continually until 1859, when it reached its maximum of 1,699,101 tons, of which 1,379,109 tons were anthracite coal. However, after repeated floods and droughts, the financial challenges that accompanied the Civil War, and a coal miners strike, in 1870 the company decided to lease the entire navigation to its competitor, the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad.

Some navigation continued along the canals of the Schuylkill into the first decades of the twentieth century, with the final commercial cargo transported in 1931. At the end of the twentieth- and into the twenty-first century, sections of the canal, like the one in Manayunk, underwent restoration to promote recreation and commemorate the past. The canal era of the mid-nineteenth century in Pennsylvania usually has been overshadowed by the success of New York’s Erie Canal and the railroad, but the Schuylkill Navigation Company was important for its precedents in transportation innovation and the tremendous amount of fuel, both coal and waterpower from the canals, carried to Philadelphia’s rapidly industrializing economy.

Brenna O’Rourke Holland is Visiting Assistant Professor of History at the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia. She earned her Ph.D. in history at Temple University. Her dissertation, “Free Market Family: Gender, Capitalism, and the Life of Stephen Girard,” is a cultural biography of Philadelphia merchant-turned-banker Stephen Girard that interrogates the relationship between family and capitalism in the early American republic. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- History of the Schuykill Navigation Company (Reading Community College)

- History of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park)

- The Canal Era (USHistory.org)

- Manayunk Canal Restoration Begins (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Origins of the City Branch? Canal, Natural & Man-Made (Hidden City Philadelphia)