Peale’s Philadelphia Museum

Essay

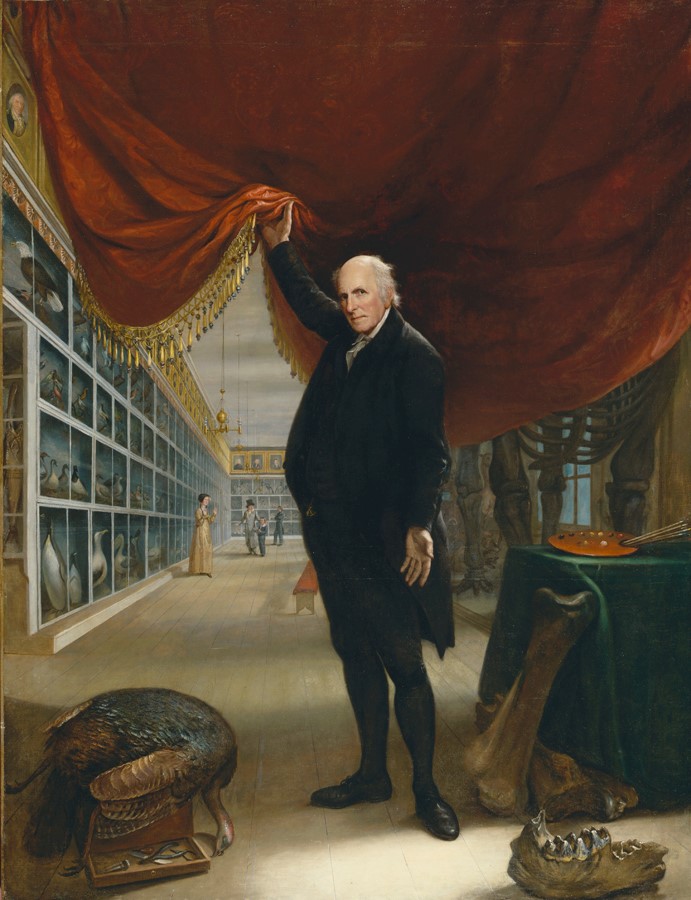

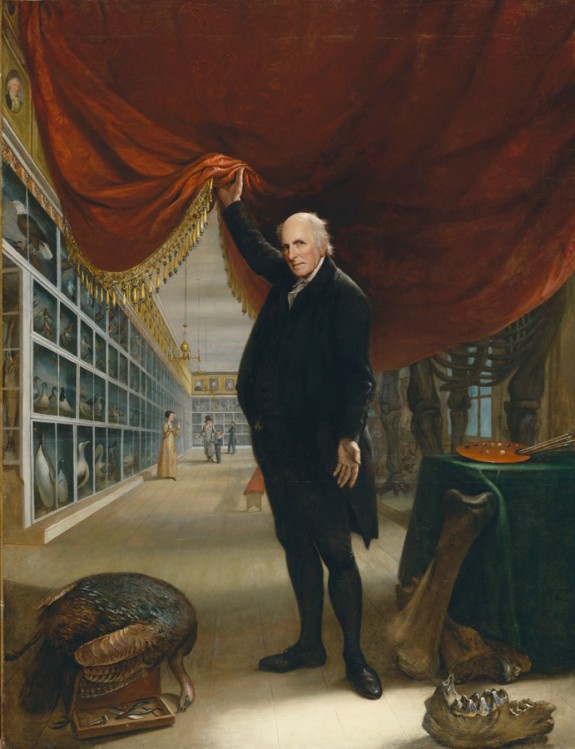

Inspired by eighteenth-century Enlightenment ideals celebrating humankind’s capacity to learn and use new information, the artist Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) conceived his Philadelphia Museum. In it, Peale intended the works of man and nature to coexist for the edification of all. The Philadelphia Museum, Peale said, served “to instruct the mind and sow the seeds of Virtue” in the new, American republic. For nearly fifty years, Peale and his family filled the museum with hundreds of painted portraits, thousands of natural history specimens, minerals, models, Asian and American Indian artifacts, archaeological objects, life-size wax figures, fossils, and curiosities—all exhibited to an international public.

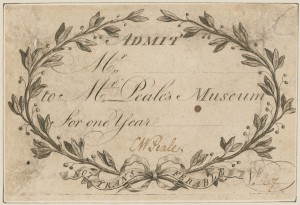

Peale developed his museum as an offshoot of his portrait-painting business. Drawn to Philadelphia by the large city’s client potential, Peale arrived in 1775 and quickly secured private portrait commissions. Seeking to market his painterly skill, Peale displayed the portraits of Revolutionary War officers in his home at Third and Lombard Streets. The display’s popularity suggested a business opportunity in the form of a pay-for-admission exhibit. Encouraged by family and friends, Peale formally announced the opening of the Philadelphia Museum in 1784 with a display of forty-four portraits that depicted “worthy personages” of America’s Revolutionary era.

Peale’s Philadelphia Museum grew quickly. To accommodate the Museum’s expansion, Peale moved it and his family in 1794 to the American Philosophical Society (America’s first scientific society) at Fifth and Chestnut Streets. There, Peale served as librarian while he increased his own museum collection of natural history specimens and paintings. The museum also had a large, live menagerie that included among its inhabitants two grizzly bears, a monkey, and an American bald eagle. Peale spent much of the 1790s studying, preparing, and installing natural history specimens in new exhibits.

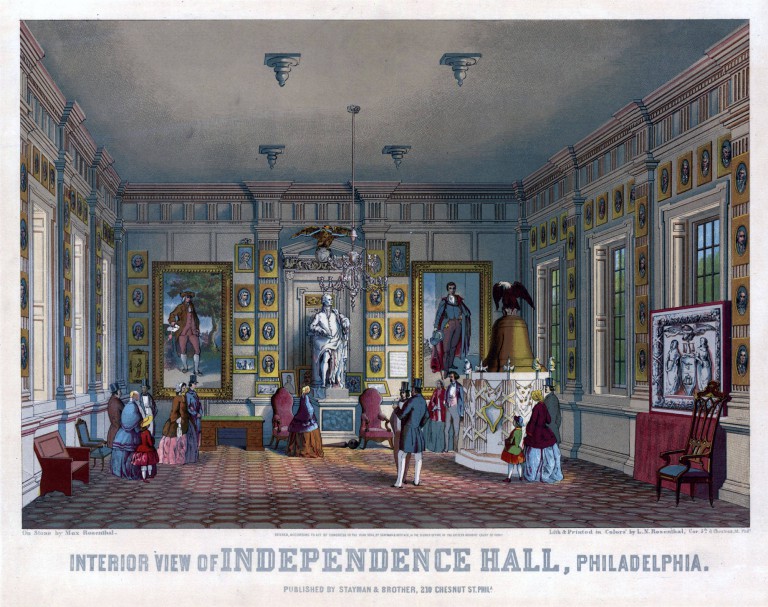

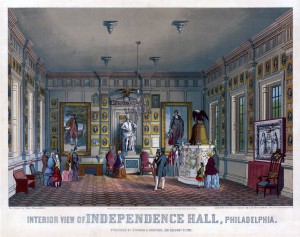

Always looking to strengthen the museum’s financial footing, Peale regularly petitioned both state and federal governments for endorsements. Not even fellow naturalist President Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) escaped Peale’s museum marketing. Although Peale never received a monetary subsidy, he secured a high public profile for the museum when the state of Pennsylvania loaned its former State House, now called Independence Hall, to him in 1802. Pennsylvania’s State House, where the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution were created, provided the Philadelphia Museum with an illustrious historic setting that added weight to Peale’s didactic mission.

On the second floor of the Pennsylvania State House, the Philadelphia Museum reached its zenith. Museum visitors received a printed catalog with which to organize their study of the exhibits. Peale and his sons arranged the collections according to the classification system developed by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707-78). Each exhibit included a painted backdrop that simulated the habitat of the specimen(s) displayed therein—a novel technique at the time. By 1811, the museum featured a Quadruped Room, a Marine Room, and a Mammoth Room that displayed the reassembled, nearly complete skeleton of a mastodon excavated by Peale in New York state. The painted portraits of famous Americans and Europeans hung in the museum’s Long Room above glass cases holding birds, reptiles, insects, minerals, and fossils.

Supplied with specimens by government-sponsored scientific expeditions like those of Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809) and William Clark (1770-1838) and Stephen H. Long (1784-1864)—from which Peale’s son, Titian (1799-1885), returned with a vast butterfly collection—the Philadelphia Museum also included American Indian clothing, weapons, and household objects. Charles Willson Peale’s son, Franklin (1795-1870), would later bring to the Museum objects from voyages to Hawaii, the Fiji Islands, and South America. Throughout the museum’s existence, citizens donated historical relics, like the thimble of Martha Washington (1731-1802), for inclusion in its displays.

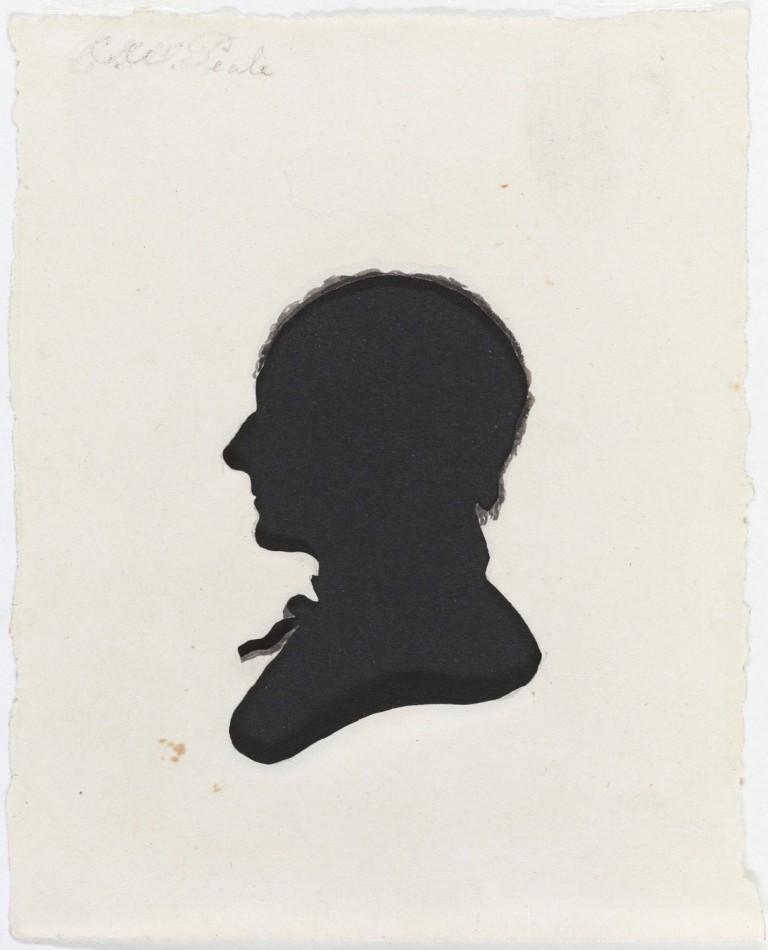

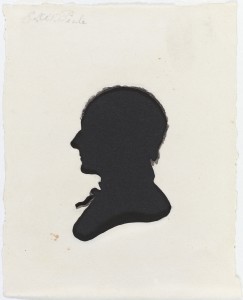

Mindful that exhibits were not enough to insure repeat museum visitation, Peale also provided “rational amusements” to his patrons. Scientific lectures, technical demonstrations (including a static electric machine), and musical entertainment took place in the museum’s lecture hall. The Philadelphia Museum often hosted public firsts including the Columbianum in 1795 (America’s first art society exhibit), the physiognotrace in 1802 (an instrument newly brought from England with which an operator traced a person’s profile and used it to cut paper silhouette portraits), and gas lighting in 1816 (the first in a Philadelphia public building).

Despite the Philadelphia Museum’s innovations, Peale’s sons advised their father that the museum faced stiff competition from other places of amusement that had appeared in many American cities. Bound by the museum’s purpose to inform and educate, Peale vowed never to stoop to a level of low public entertainment. However, he had added both natural curiosities (like a five-legged calf) and sensational objects (like the trigger finger of a convicted murderer) to the museum’s exhibits. And, the Philadelphia Museum expanded to include branches in Baltimore (1814) and New York City (1825). Managed by Peale’s eldest sons, Rubens (1784-1865) and Rembrandt (1778-1860), respectively, these branch museums included the same kinds of exhibits although smaller in number.

Always subject to financial crises and changing public tastes, the Philadelphia Museum struggled to maintain its prominence as the nineteenth century unfolded. Just after Peale’s death in 1827, the museum moved from the Pennsylvania State House one block west to the new and larger Chestnut Street Arcade. After two subsequent museum relocations, burdened by rising maintenance costs unmet by admission revenues, the Peale family sold the museum collection (except for the portraits) in 1849.

The Philadelphia Museum collection’s buyers, Phineas T. Barnum (1810-91) and Moses Kimball (1809-95), had their own museums in Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. Within a short time, all of them experienced a series of fires and financial hardships that destroyed or dispersed their holdings. By the early twentieth century the former Philadelphia Museum’s vast natural history and ethnographic collection was known only by four bird specimens at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology and possibly (records are unclear) some American Indian and Oceanic artifacts at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

Happily, the Philadelphia Museum’s portrait collection survives in large part. Sold at auction in 1854, the museum portraits went to a wide range of public and private owners. The largest single buyer was the City of Philadelphia, which purchased a group of Philadelphia Museum portraits for display in Independence Hall. That group of museum paintings subsequently became part of the collection of Independence National Historical Park. The paintings continued to hang together, as in Peale’s time, embodying the Philadelphia Museum’s mission “to please and entertain the Public.”

Karie Diethorn is the Chief Curator of Independence National Historical Park–the home of Independence Hall, the Liberty Bell, and nearly one hundred portraits from Peale’s Philadelphia Museum.

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Peale Museum Interactive (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Museum Collections, Independence National Historical Park

- Charles Willson Peale (Collections Online, Philadelphia Museum of Art)

- The Long Room, Interior of Front Room of Peale's Museum (Detroit Institute of Arts)

- An American Behemoth: Peale's Mastodon (American Philosophical Society)

- Peale's Mastodon (Common-Place)

- Titian Peale Butterfly and Moth Collection (Academy of Natural Sciences)

- Philadelphia Museum Shaped Early American Culture (NPR)