Cartoons and Cartoonists

Essay

American cartooning began in Philadelphia. Benjamin Franklin (1706–90), who introduced cartoons to North America, used images to galvanize viewers to action on the issues of their day. As the political, economic, and cultural capital of the early United States, Philadelphia became a center for producing political cartoons and humorous caricatures. Although New York eventually supplanted Philadelphia as the nation’s primary publishing center, Philadelphia cartoonists and their work continued to thrive and influence the art of cartooning, politics, and popular culture of readers throughout the nation.

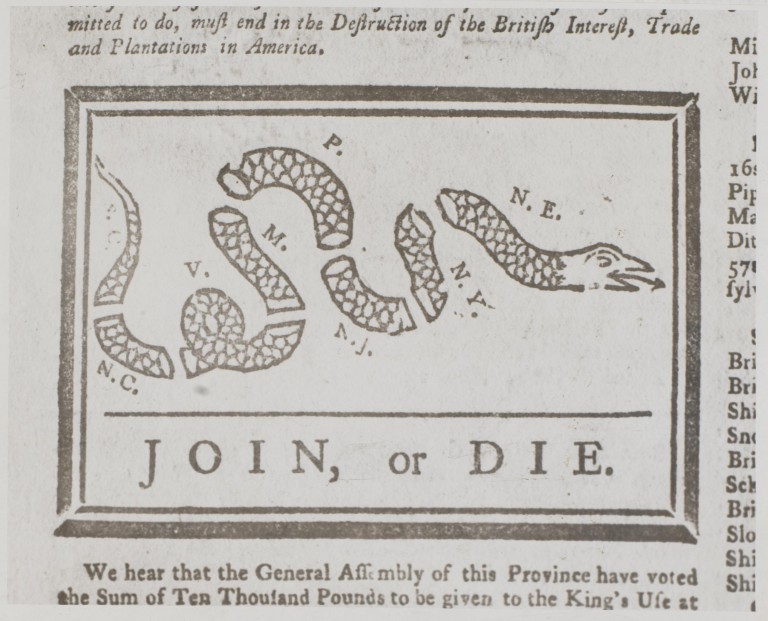

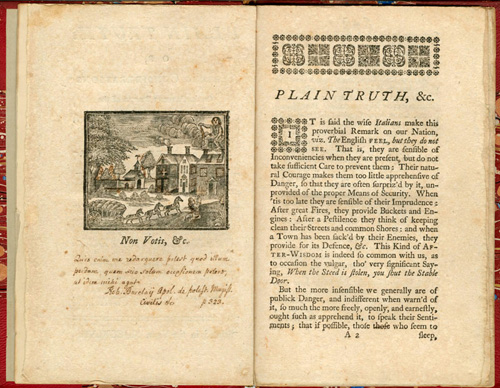

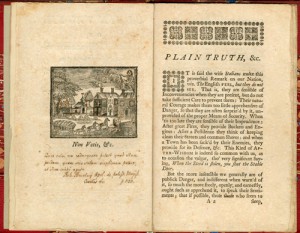

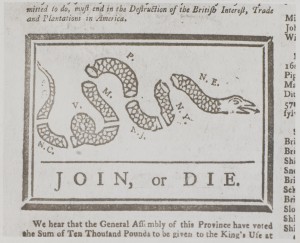

Many historians consider “Join, or Die,” the iconic image of the segmented snake representing the American colonies, published in the Pennsylvania Gazette in May 1754, to be the first political cartoon published in America; it was certainly the first cartoon published in an American newspaper. Some consider “Non Votis,” a lesser-known illustration of a hapless wagoner appealing in vain to Hercules, from the political pamphlet Plain Truth (1747), to be the first American political cartoon. Whichever image deserves the honor, Franklin was responsible. Both affected the political climate of their day. Plain Truth and its imagery helped mobilize militia volunteers against the French. “Join, or Die,” quickly appeared in almost every newspaper in America as a rallying cry for colonial unity during the French and Indian War. It later became a popular pro-colonist image during the American Revolution.

Ironically, Franklin was also the first American public figure widely lampooned by cartoonists. Approximately half of the cartoons known to have been published in the 1760s (most produced in Philadelphia) criticized Franklin. In 1764, in the wake of Pontiac’s War and the Paxton Riot, illustrated pamphlets and broadsides flew back and forth—some going as far as to depict Franklin as a devil. These negative caricatures contributed to Franklin’s defeat in the Pennsylvania Assembly election of 1764.

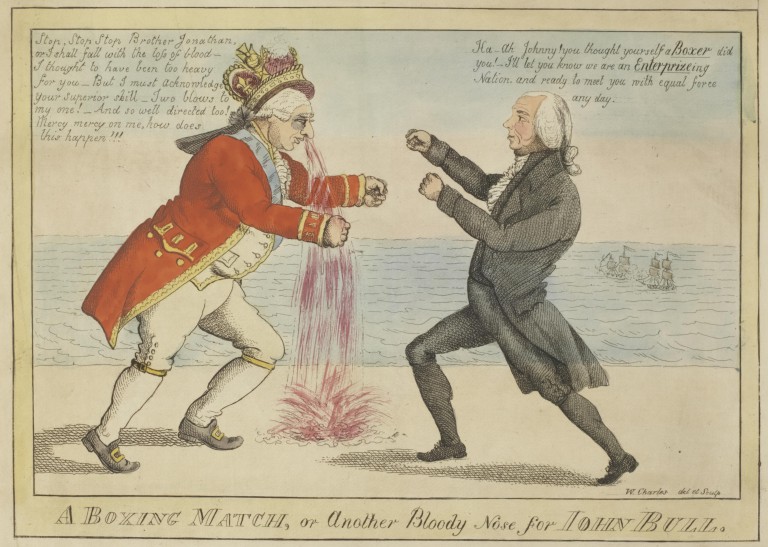

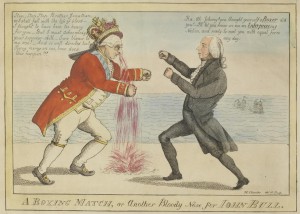

During the War of 1812, Philadelphia’s cartoonists celebrated U.S. victories against the British and introduced cartoon characters that came to symbolize the United States and its people. Scottish-born etcher and children’s-book illustrator William Charles (1776–1820) churned out dozens of political etchings commenting on the war. During the War of 1812, “Brother Jonathan,” a country bumpkin character widely considered a precursor to Uncle Sam, came to personify the United States. Philadelphia cartoonists such as James Akin (1773–1846) popularized Brother Jonathan and other symbolic characters such as Columbia (female personification of America and freedom) and Major Jack Downing (another American everyman character and Uncle Sam precursor).

The Boost of Lithography

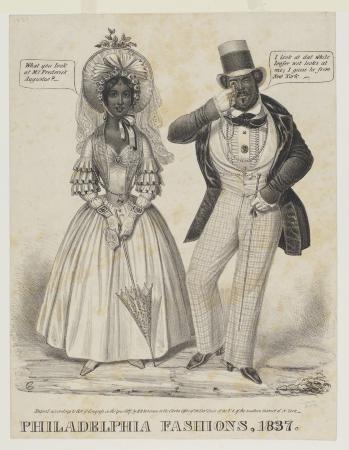

Prior to the 1830s, cartoons, engraved in copper or carved into wood, were expensive and time-consuming to produce. The introduction of lithography allowed images to be cheaply and easily reproduced, and cartoons proliferated. Beginning in 1828 and 1829, commercial lithographic firms established in Philadelphia, a major hub of this activity, published prints of all varieties, including cartoons and caricatures. Politics during the Jacksonian era provided plenty of fodder, and Philadelphia firms published widely circulated, biting artistic commentaries by artists such as David Claypoole Johnston (1799–1865) and Edward Williams (E. W.) Clay (1799–1857). Between 1828 and 1830, the Philadelphia-born Clay produced his most famous series of prints, Life in Philadelphia, in which he parodied middle-class African Americans for their perceived social and political aspirations. Clay’s racist caricatures were hugely popular and were reproduced and imitated by cartoonists in New York, London, and other cities.

Philadelphia-area lithographers still did brisk business and boasted influential cartoonists in the 1850s, though New York printers now dominated the American lithographic printing industry. John L. Magee (b. 1820?), for instance, produced numerous cartoons throughout the 1850s and 1860s that commented ironically on trends and events in Philadelphia and its environs, deplored the spread of slavery, championed the Union cause, and criticized the Reconstruction policies of President Andrew Johnson (1808–75).

In the 1850s and 1860s, while New York–based magazines such as Harper’s Weekly, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Magazine, and Vanity Fair launched the careers of several cartoonists, Philadelphia continued to play a role. The accomplished illustrator Felix O. C. Darley (1822–88) of Philadelphia and Delaware contributed fanciful cover illustrations for humor magazines such as the John-Donkey and the Lantern. Henry Louis Stephens (1824–82) of Philadelphia and Bayonne, New Jersey, drew caricatures for Leslie’s and Harper’s as well as illustrating and co-editing Vanity Fair.

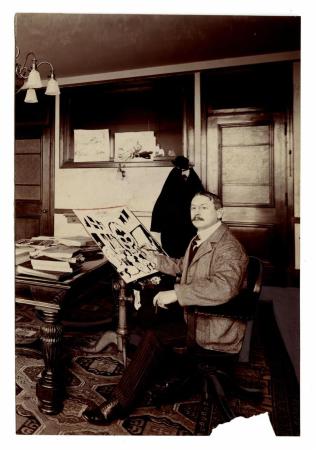

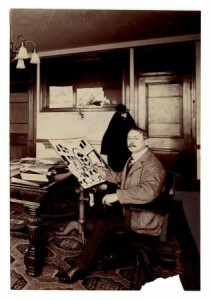

With the rise of the daily newspaper cartoon from the late 1880s into the 1910s, Philadelphia cartoonists gained a new opportunity to shine. Philadelphia newspapers cultivated hosts of freelance and staff cartoonists. Some papers even printed their work in color. Cartoons and simple line drawings, easily produced with high-speed presses, now capable of printing in color, grabbed readers’ attentions. Philadelphia daily newspapers such as the North American, Inquirer, Public Ledger, and Record often published cartoons on their front pages. Several syndicated their content. Editors typically gave cartoonists free rein, and many produced political cartoons commenting on national and local people and events, sometimes as part of ongoing series. Walt McDougall (1858–1938), a staff cartoonist at the North American, claims credit for coining the term “graft”—then a carnival term for chicanery—as a non-libelous synonym for political corruption in a series that introduced a dinosaur-like “graft monster” to newspaper readers. McDougall was also co-producer of the first color comic strip in America, The Unfortunate Fate of a Well-Intended Dog (1894).

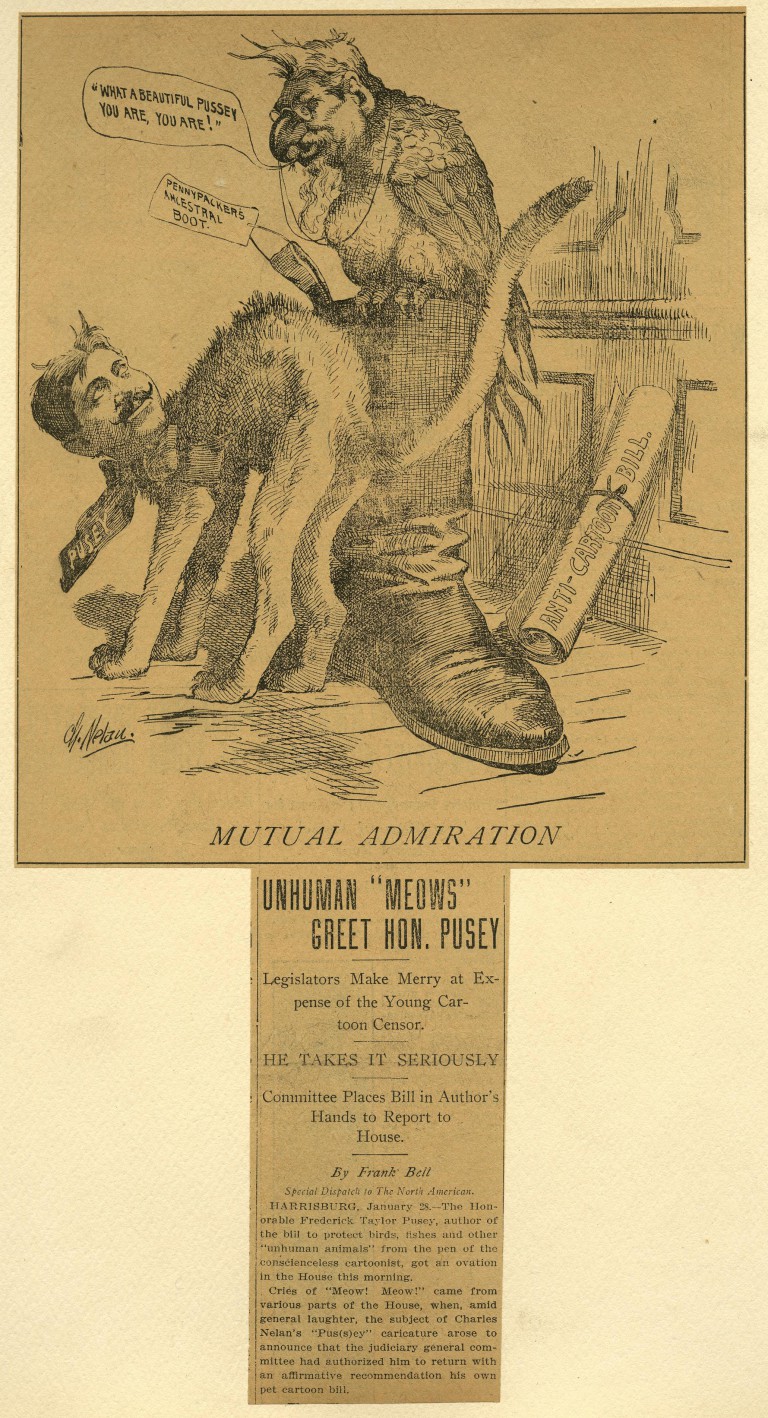

The Anti-Cartooning Law, 1903

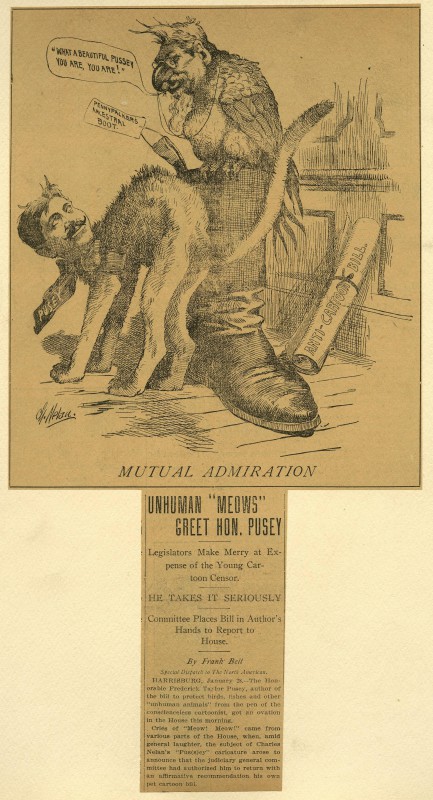

Philadelphia newspaper cartoonists made national headlines around the turn of the century when cartoonists at the North American inspired the Pennsylvania state legislature to pass the Salus-Grady libel law (also known as the Anti-Cartooning Law) in 1903. Provoked by a series of cartoons by Charles Nelan (1858–1904) during the gubernatorial election of 1902 that depicted Governor Samuel Pennypacker (1843–1916) as a parrot, mindlessly squawking the words of his party boss (and relative) Matthew Quay (1833–1904), it banned cartoons or caricatures that depicted people as nonhuman animals. Nelan also mocked Pennsylvania state representative Frederick Taylor Pusey (1872–1936), who introduced the bill to the legislature, by depicting him as a “Pus(s)ey cat.” McDougall reacted to the bill’s passage by immediately publishing caricatures of Pennypacker and other Pennsylvania politicians as non-animal objects, such as oak trees, beets, chestnut burrs, beer steins, and turnips. Newspaper cartoonists in Philadelphia and elsewhere published caricatures of public officials as a virtual menagerie of different animals. The Salus-Grady law was never enforced and was rescinded shortly after Pennypacker’s term as governor ended.

Many newspaper cartoonists also created nonpolitical drawings for sports and children’s pages and experimented with early versions of the comic strip. Philadelphia cartoonists created a number of strips of varying popularity and longevity. Some, including The Little Quakers (H. E. Godwin [n.d.], Inquirer, 1903–04), Little Billy Penn and His Doggy Schuylkill (Hy Gage [1878–1971], Record, 1906), It’s Philadelphia (Robert Vance [n.d.], Bulletin, 1947–54), and Silly Philly (Bil Keane [1922–2011], Bulletin, 1947–61), were of primarily local interest. Philadelphia cartoonists also created widely syndicated strips, such as Adventures of Willie Green (1906–20s), by Harris Brown (1884–1962), and Little Lulu (1935), by Marge (Marjorie Henderson Buell [1904–93]). Evening Ledger cartoonist and Temple University professor John J. Liney (1912–82) became the primary artist of the nationally syndicated Henry comic strip from 1945 to 1979. From at least the 1920s, when it ran the comic strip I Am Proud That I Am a Negro by “Jay Bee” Davidson, the Philadelphia Tribune incubated the talents of African American cartoonists, including the National Newspaper Publishers Association award–winning Samuel Joyner (b. 1924).

In the mid-twentieth century, Philadelphia-based editorial cartoonists such as Charles Henry (“Bill”) Sykes (1882–1942) in the 1910s–40s and Herbert Johnson (1878–1947) and Jerry Doyle (1898–1986) in the 1930s–40s drew influential cartoons that commented on World Wars I and II, the Depression and New Deal, workers’ rights, socialism, fascism, and American politics. Many comic historians credit Doyle with inventing “John Q. Public” as a symbol of the everyday American.

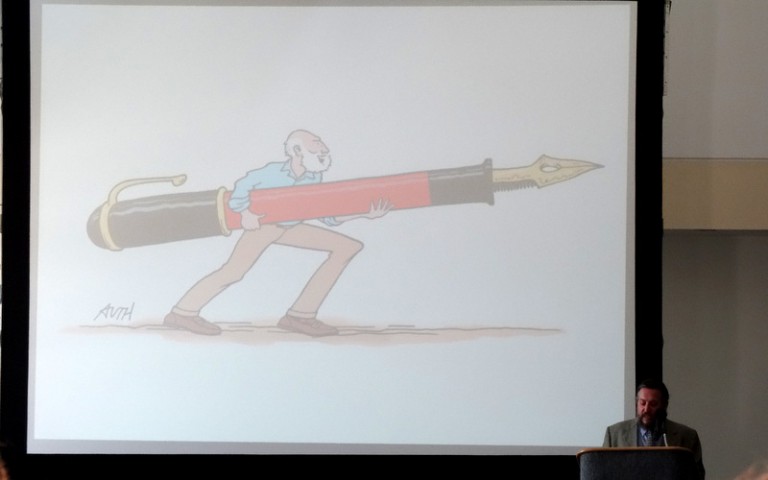

Two Pulitzer Winners

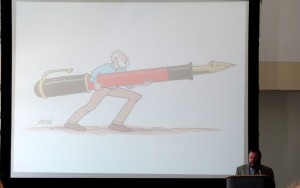

In 1976, Tony Auth (1942–2014) of the Inquirer became the first Philadelphian to win the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning. In 1992, Signe Wilkinson (b. 1959), cartoonist for the Inquirer and the Daily News, became the first female cartoonist to win this honor. Both artists’ careers were affected by the technological changes—notably, the rise of the internet and of digital media—and the decline of the newspaper industry in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Auth, who enjoyed a long and illustrious career at the Inquirer for forty-one years, made a major transition when, in 2012, he began cartooning in a new medium, becoming the first “digital artist in residence” at NewsWorks.org, a web-based news portal of Philadelphia’s WHYY radio. Transitioning from the traditional drawing board to an app on his iPad, Auth continued to produce award-winning syndicated cartoons for NewsWorks until his death in 2014. With Auth’s death, Wilkinson, who has drawn cartoons for the Daily News since 1985, became the only remaining political cartoonist for a major Philadelphia newspaper, although readers became increasingly likelier to encounter her cartoons online at Philly.com than on the printed pages of the Inquirer or the Daily News.

By the turn of the twenty-first century, as newspapers ran fewer and fewer comic strips—many cutting their comics sections entirely—so too did the number of Philadelphia-based comic strip artists decline. In the early twenty-first century, however, the Philadelphia area boasted at least two nationally syndicated comic strip artists: Robb Armstrong’s Jump Start (1989–), centered on an African American family in Philadelphia, and Terry and Patty Laban’s Edge City (2000–16), which explored the lives of a suburban Jewish family. Members of the Philadelphia Cartoonist Society, founded in 1997, kept the art of cartooning alive in the metropolitan area as they continued to push the boundaries of cartooning in its various forms—including comic strips, editorial cartoons, underground/alternative art, and web comics. Throughout the late twentieth century and continuing into the twenty-first, Philadelphia cartoonists, although smaller in number, continued the proud tradition of political commentary begun in the colonial era by Benjamin Franklin.

Rachel Moloshok is managing editor of publications and associate manager of scholarly programs at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, where she has helped to plan and execute several digital history exhibits, including Politics in Graphic Detail: Exploring History through Political Cartoons (2015). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- America on Stone: 19th Century American Lithographs (National Museum of History, Smithsonian)

- Drawn Into Politics (Free Library of Philadelphia)

- E. W. Clay’s Life in Philadelphia Series (University of Virginia)

- HarpWeek

- Politics in Graphic Detail: Exploring History Through Political Cartoons (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Historic Images, New Technologies (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- It’s No Laughing Matter (Library of Congress)

- Philadelphia on Stone (Library Company of Philadelphia)

- Political Cartoons and Public Debates (Library of Congress)

- Signe Wilkinson’s website

- Stripper’s Guide

- Tony Auth’s website

- Philadelphia Cartoonist Society

- Little Lulu Comes to Harvard (Harvard Gazette, November 2, 2006)