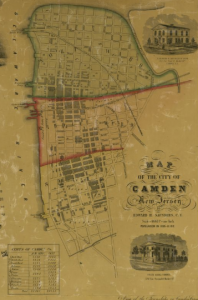

Camden, New Jersey

By Howard Gillette Jr. | County Seat

Essay

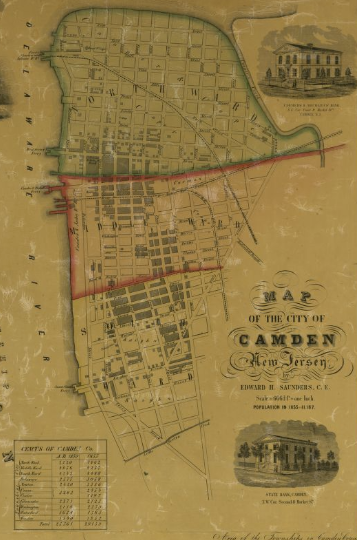

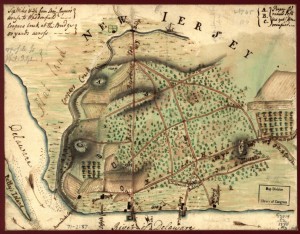

Incorporated in 1828 and named county seat of the newly formed Camden County when it separated from Gloucester County in 1844, Camden City long served as the heart of the South Jersey region directly across the Delaware River from Philadelphia. Besieged in the second half of the twentieth century by losses of population and economic instability as industry declined, Camden lost its once premier standing as it struggled with high levels of poverty, crime, and environmental degradation. Despite multiple initiatives intended to revive its fortunes and the resilience of its residents and anchor institutions, the city remained a drag on regional prosperity into the early years of the twenty-first century.

Initially boosted by ferries connecting settlement in West Jersey to Philadelphia across the Delaware River, the area that became Camden capitalized on its strategic location for shipping. Its position further improved with the arrival of the Camden and Amboy Railroad in 1834, a primary link between Philadelphia and New York City. Although the town remained in Philadelphia’s shadow through the Civil War, with peace it attracted both the immigrant workforce and the capital needed to establish its own industrial base. In addition to a host of small firms, Camden became home to major manufacturing companies at the turn of the new century: most prominently Campbell Soup, New York Ship, and RCA Victor. The concentration of opportunity drew migrants from the United States and abroad. From a population of only 14,358 in 1860, the city reached nearly 76,000 by 1900.

Among those drawn to the city in the aftermath of the Civil War was Walt Whitman (1819-92). Following the traumatic experience of comforting Union troops during the war while based in the nation’s capital, Whitman sought relief for his poor health by moving into his brother George’s home in Camden in 1873. Subsequently moving into a snug home—the only one he ever owned—a few blocks away on Mickle Street (subsequently MLK Boulevard) near the waterfront, Whitman relished the remaining years of his life in the city. A frequent visitor by ferry to Philadelphia, he claimed that such trips reminded him of the experiences in his youth that informed his poem “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” At the time of Whitman’s death, an extended procession, headed by Whitman’s close friend the Philadelphia artist Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), made its way to burial at Harleigh Cemetery at the city’s edge, where the tomb of the poet’s own design continued to attract admirers into the twenty-first century.

The prosperous 1920s appeared to signal unlimited possibilities for Camden. Linked in 1926 to Philadelphia by the largest single span suspension bridge in the world at the time, Camden touted its connection across the Delaware River as the boost it needed to become a “second Brooklyn.” Boosters envisioned the formation of a “Greater Camden” encompassing the city’s surrounding towns and dominating South Jersey.

Growth Until 1950s

Camden never extended its boundaries, but the city continued to grow in population and influence into the early 1950s, as long its big three businesses thrived. Built upon a tightly knit neighborhood structure, often centered on Catholic parishes with distinct ethnic identities, Camden survived the ill effects of the Great Depression and once again rose to prominence with the boost World War II gave to its industries. The combination of corporate restructuring and demographic change altered the city’s trajectory after the war, however. Both RCA and Campbell’s Soup decentralized their primary production operations, in part to avoid rising labor costs as previously unorganized workers unionized. Losing its favored position to newer facilities in other parts of the country, New York Ship’s employment dropped precipitously from a height of 47,000 workers during the war and shut down entirely in 1967. From a height of nearly 125,000 people in 1950, the city’s population declined to just over 100,000 in 1970.

For most of its history, Camden dominated the surrounding area, offering the broadest range of employment, shopping, and entertainment options to area residents. As residents left the city for the surrounding suburbs, however, Camden ceased to be the primary destination it had been for generations. Decentralization of commerce as well as population took a major turn when the Cherry Hill Mall, the first enclosed shopping center on the East Coast, opened in Delaware Township (soon thereafter renamed Cherry Hill itself) in 1961. Within a few years, the property valuation of Cherry Hill surpassed that of Camden, a gap that only widened over time despite the suburb’s smaller number of residents. Other professional services, notably law, also decentralized, though hospital services largely remained in the city, despite some interest at both Cooper and Lady of Lourdes in relocating to the suburbs.

As a relatively small minority before World War II, Camden’s African American population concentrated in parts of South and East Camden, occupying the few homes that they were not barred from and facing strict segregation in a host of public facilities. As their numbers grew during and after the war, they pressed for civil rights, especially more housing options in both publicly and privately constructed facilities. A robust urban renewal program launched in the early 1960s made the housing crisis worse, however, by demolishing many older homes occupied by Black residents. Protests followed, culminating in 1971 when news that a city policeman had shot a Puerto Rican motorist set off more than three days of civil disturbances. Already pulled to the suburbs by the promise of new housing at affordable rates, Camden’s white ethnic residents accelerated their departure from the city. In the decade after the riots, the white population fell from 61,303 to 26,003. In the same period, the percentage of the population that was Black climbed from 39 to 53 percent. In 2010 the city’s population, which had fallen below 80,000, was 44 percent African American and 47 percent Hispanic.

Waterfront as Tourist Destination

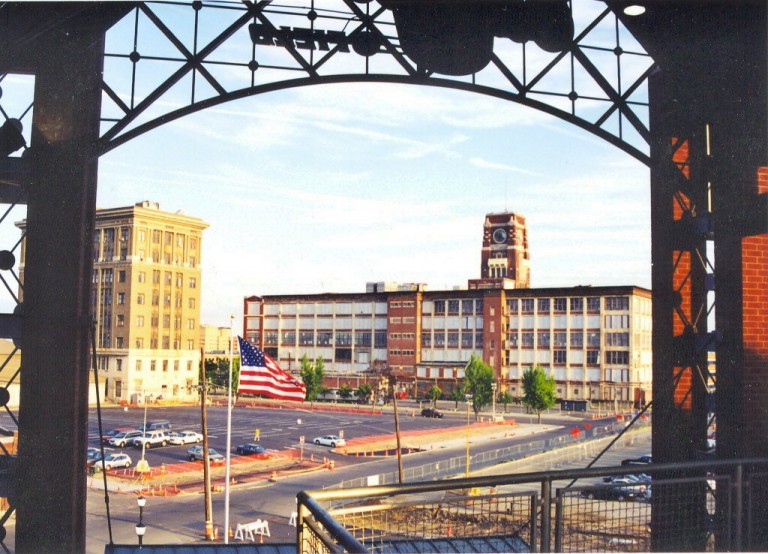

When national funding for redevelopment dried up in the mid-1970s, Camden officials sought other options for revitalization. Following the example of urban shopping centers pioneered by Baltimore’s James Rouse, city officials worked to convert the largely abandoned industrial sites on its waterfront to a tourist destination. A state aquarium served as the centerpiece of that early effort in the 1980s. Plans called for accompanying business development, notably the relocation of Campbell Soup’s headquarters from a campus largely set apart from the city on Admiral Wilson Boulevard. A change of leadership led to a reversal of Campbell’s decision, however, and for years the semi-public agency established to develop the waterfront, Cooper Ferry Development Corporation, struggled to complete its ambitious vision

Other initiatives targeted Camden’s high-poverty neighborhoods, including some of the most effective community development corporations in the region. Often affiliated with a parish, these organizations secured funding for housing rehabilitation and undertook a number of associated community-driven programs. Such efforts helped stabilize parts of the city, without, however, eliminating the associated costs of highly concentrated poverty: crime, poor health, and school dropouts.

Depressed property values and continued loss of business kept Camden city for years from raising sufficient revenues to meet its obligations, forcing the state to provide the funds constitutionally required to balance the city’s budget annually. Seeking to contain those expenses, the state first established an oversight board to monitor the city’s expenses. Subsequently, in 2002, it took control of the entire city by putting its own chief operating officer in charge of day-to-day city business. Accompanied by $175 million in funding set aside as leverage to attract new business to the city, the state undertook a comprehensive planning process aimed at attracting sufficient reinvestment to replenish the city’s revenues. The state takeover lasted seven years, without substantially reducing the city’s structural deficit. Democrats in the state legislature terminated the program before Republican governor-elect Chris Christie (b.1962) could take charge.

Such machinations proved unnecessary. Seeing a way of getting enough votes from the Democratic legislature to advance his programs, Governor Christie showered Democratic power brokers based in South Jersey with favors for Camden, including more than $1 billion in tax incentives to lure new businesses to the city. Hardly a boost to Camden residents themselves, who were ill prepared by education and training to fill these largely white collar positions, Christie’s approach at least offered the prospect of recentering Camden in South Jersey. Together with a handful of outstanding educational and medical institutions committed to building their presence in Camden, these new investments helped boost Camden as a destination. Whether such investments would bring with them further means for preparing Camden residents for the opportunities they represented remained to be seen. In the meantime, political opposition to opening up suburbs to greater numbers of affordable housing units meant that as much as Camden’s business fortunes might rise in subsequent years, new companies were likely to encounter a sea of poverty around them.

Howard Gillette Jr. is Professor Emeritus of History at Rutgers-Camden and author of Camden After The Fall: Decline and Renewal in a Post-industrial City. He is co-editor of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Campbell's Soup takes on hunger and obesity in Camden (WHYY, February 11, 2016)

- Camden trades 'goods for guns' (WHYY, December 28, 2011)

- Camden City police department to be dismantled (WHYY, August 11, 2012)

- County police going door to door in Camden (WHYY, May 1, 2013)

- Camden County police see evidence of improvement (WHYY, August 15, 2013)

- No, we're not Camden -- but what is Philadelphia's problem? (WHYY, March 27, 2014)

- Was building Camden's baseball stadium a mistake? (WHYY, April 1, 2014)

- In representing Camden crime, let's set the picture straight (WHYY, February 25, 2014)

- Christie heads to Camden to promote business (WHYY, July 14, 2014)

- Water company could bring 600 jobs to Camden with incentives (WHYY, June 9, 2015)

- New art and wine festival coming to the Camden Waterfront Saturday (WHYY, July 28, 2015)

- Camden minor league team says it's folding after 15 seasons (WHYY, October 21, 2015)

- Subaru breaks ground on new Camden headquarters (WHYY, December 9, 2015)

- Before Constitution Center honors, civil rights icon visits Camden and memories of MLK (WHYY, September 20, 2016)

- The billion dollar giveaway in Camden (WHYY, November 15, 2016)

- Adopting new approach helps Camden job-training organization better serve youth (WHYY, March 1, 2017)

- Camden metro area sees highest year-over-year job growth nationwide (WHYY, April 25, 2017)

- Camden council leader wins mayoral race (Associated Press via WHYY, June 6, 2017)

- Subaru opens its doors in Camden, thanks to generous N.J. tax break (WHYY, April 27, 2018)

- Camden breaks ground for first new hoel in 50 years (WHYY, May 21, 2019)

Links

- City of Camden

- City of Camden Interactive History Mural

- Camden County Historical Society

- The Walt Whitman Archive

- Walt Whitman Papers Online (Library of Congress)

- The Changing Landscape of Camden, New Jersey (Rutgers University)

- Coopers Ferry Partnership

- Heart of Camden

- Rutgers University-Camden

- Cooper University Health Care

- What's Changing in Camden? (CivicStory via YouTube)