Art of Thomas Eakins

Essay

The art of Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) is more deeply entwined with the city of Philadelphia than that of any other artist of the nineteenth century. Born in North Philadelphia in 1844, Eakins spent nearly his entire life in the city. He consistently took local residents as his subjects, portraying friends, family, and individuals he admired engaged in professional activities and leisure pursuits. His oil paintings, watercolors, sculptures, and photographs vividly reflected late-nineteenth-century life in Philadelphia and had a lasting impact upon generations of American artists.

Eakins received his first art lessons from his father, Benjamin Eakins (1818–99). A writing master and teacher, Benjamin imparted to his son the precision of fine penmanship and calligraphy. Eakins employed his deft control of the pen in his drawing classes at Central High School, where he learned to create meticulous mechanical and perspective drawings. His growing interest in art led him to enroll at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA, then located on Chestnut Street between Tenth and Eleventh Streets) in 1862. He initially took antique-cast drawing classes—the main course of study for students—before he registered for life classes in the spring of 1863. Seeking greater insight into the structure of the human form, he supplemented his art courses with anatomy lectures and dissections at Jefferson Medical College (later Thomas Jefferson University).

After four years of instruction at PAFA, Eakins pursued further artistic training abroad. From 1866 to 1869, he attended the École des Beaux Arts in Paris. Under the guidance of the leading academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), he gained a strong command of drawing the nude figure. He also learned to sculpt from Augustin-Alexandre Dumont (1801-84), creating small maquettes as aids to painting—a practice he continued throughout his career. Eakins then spent the winter of 1869-70 in Spain, where he became enraptured with the dark colors and bold, gestural brushstrokes of the seventeenth-century paintings of Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) and José de Ribera (1591-1652). Stimulated by his artistic discoveries and emboldened by his academic training, Eakins created his first large-scale oil painting, A Street Scene in Seville (1870).

Early Athletic Scenes

Eakins returned to Philadelphia in July 1870. He set up his studio at his childhood home at 1729 Mount Vernon Street, where he lived for the rest of his life. He painted relatives and friends, predominantly women, engaged in everyday activities in domestic interiors. He was also inspired by the outdoor sports he had enjoyed since youth: rowing, fishing, hunting, and sailing. Eakins embarked upon a series of oil paintings and watercolors of male athletes at identifiable locations in the Philadelphia region. As such scholars as Elizabeth Johns and Martin A. Berger have argued, Eakins’s sporting pictures reflected his community’s growing interest in modern leisure and its changing constructions of masculinity. After the Civil War, a rise in economic prosperity and an increasing preoccupation with physical health led Americans to pursue recreational activities outdoors. Although both sexes participated in athletics, physical fitness became associated with manhood; a strong body demonstrated a strong mind. Sculling was a particularly popular sport among middle-class men in Philadelphia, one that required rigorous discipline.

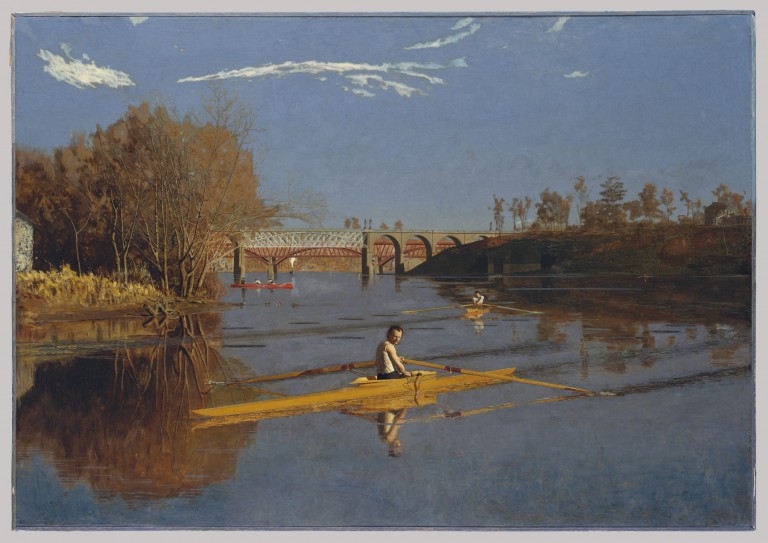

An avid rower since the 1860s, Eakins created approximately fourteen sculling works. The first and best known of these is Max Schmitt in a Single Scull (The Champion Single Sculls) of 1871. Eakins portrayed his longtime friend Max Schmitt (1843-1900) in a boat on the Schuylkill River, which was located near the artist’s home. As with all of his major works of art, Eakins created the painting through a laborious artistic process, which, as scholar Michael Leja has argued, involved the combination and reconciliation of multiple systems of knowledge: linear perspective, anatomical research, and mathematical calculation. Eakins’s methodically crafted composition celebrated a popular Philadelphia activity and paid tribute to the mental and physical dexterities of his friend, a champion oarsman.

Science and Anatomy

In April 1875, Eakins created what would become known as his masterpiece, The Gross Clinic. The monumental painting features Dr. Samuel D. Gross, a pioneering Philadelphia surgeon with whom Eakins had become acquainted at Jefferson Medical College. Gross is shown performing a bone operation with the help of five doctors in Jefferson Medical College’s surgical amphitheater. Through his dignified efforts to the save the limb of an ailing patient, Gross appears as both a healer and a teacher—the hero of a modern history painting. Eakins specifically created The Gross Clinic for the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. The art committee rejected the painting, however, offended by its bloody subject matter. Eakins displayed it in the exhibition’s medical section, where it drew attention to Philadelphia’s long history as an advanced medical center.

Eakins began working at PAFA the same year as the Centennial Exhibition. Informing his teaching with his interest in science and anatomy, he shifted PAFA’s emphasis from the study of plaster casts to the study of the nude. He insisted on the use of live models (both human and animal) in drawing and painting classes and added dissection courses to the curriculum. He also gave lectures on anatomy and invited surgeons to speak. Eakins felt that only by gaining a thorough understanding of skeletal and muscular structure could students adequately represent the human form. He exerted such a strong impact upon the institution that within only six years, he was appointed director.

Eakins’s teaching practices were deeply controversial, however. His insistence on the study of the nude in mixed-sex classes and his frequent use of pupils as models led to repeated conflicts with faculty, students, parents, and PAFA’s board. Objection to his teaching methods escalated after an incident in January 1886 in which, during an anatomy lecture on the pelvis, Eakins infamously removed the loincloth from a male model in front of female students. Exasperated by what was perceived to be consistently inappropriate and insubordinate behavior, the board forced Eakins to resign.

Despite his tarnished reputation, Eakins continued teaching after he left PAFA. He ran classes at the short-lived Art Students’ League of Philadelphia (1429 Market Street), an artists’ cooperative formed by loyal male students who seceded from PAFA after his resignation. He also lectured occasionally at the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia, the National Academy of Design in New York, and Cooper Union in New York, always insisting upon the importance of the study of the nude.

Photography

In addition to oil painting, watercolor, and sculpture, Eakins experimented with photography in the 1880s and 1890s. Using a wooden view camera and glass plate negatives, he produced platinum prints of great tonal richness. The majority of his photographs are figure studies and portraits of students, family, and friends; most were created as independent works of art. In the few instances in which Eakins utilized his pictures as preparatory aids to painting, he rarely copied them directly. More typically, he took elements from a variety of photographs and transformed them in the final work.

In the 1880s, Eakins produced a series of photographs that engaged with an Arcadian theme. He took pictures of PAFA students posing in classical drapery and in the nude, and he made several excursions with his pupils to photograph them in idyllic outdoor settings. The photographs taken on a trip to Dove Lake near Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, led to Eakins’s painting The Swimming Hole (1885). Relying upon his photographs as general references, he depicted a scene of nude young men on a rocky outcrop. Scholars such as Berger, Lloyd Goodrich, and William Innes Homer have described the painting and its related images as homosocial, or explorations of male companionship. Others, such as Whitney Davis, Jennifer Doyle, and Michael Fried, have argued that the works are homoerotic because of their emphasis on the male physique. Regardless of their reading, Swimming Hole and its related photographs reflect Eakins’s enduring interest in the human body.

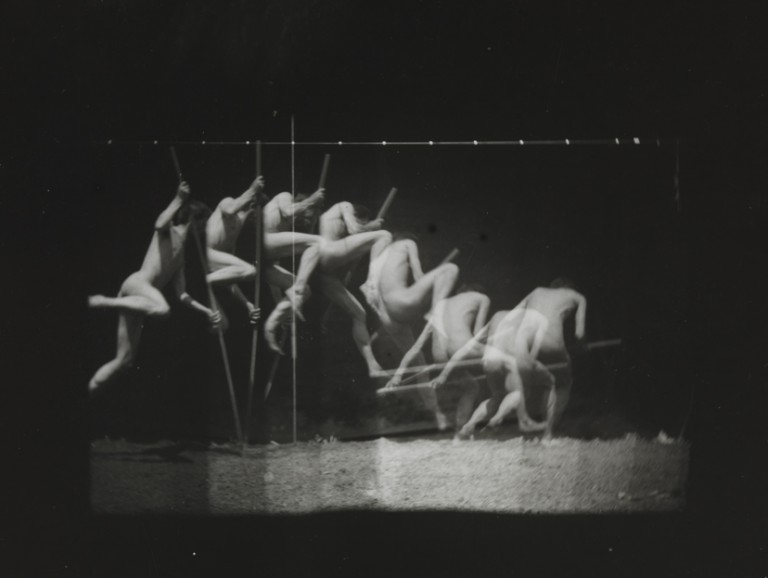

Eakins also used photography to study human and animal locomotion. In 1884, he was part of a committee at the University of Pennsylvania that oversaw the work of Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904), who had gained international renown in the 1870s for his equine photographs. Seeking to discover whether horses lifted all four hooves off the ground when galloping, Muybridge set up a series of cameras alongside a track and took sequential shots of the animals’ movements. Eakins relied upon Muybridge’s pioneering photographs in his representation of horses pulling a coach in The Fairman Rogers Four-in-Hand (A May Morning in the Park) (1879-80). Eakins also carried out his own photographic studies of motion as part of his ongoing quest to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the human body. He photographed men walking, running, jumping, and pole-vaulting in the nude.

Late Paintings

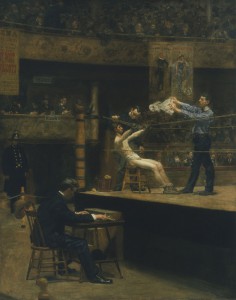

Eakins briefly returned to athletic subjects in 1898 and 1899, producing a small number of boxing and wrestling paintings. As with his earlier rowing, hunting, and sailing scenes, the inspiration for these works arose from his enthusiasm for the sports. He attended matches at the Philadelphia Arena (then at Broad Street and Cherry Street, diagonally across from PAFA) and used professional fighters as his models.

Except for these few sporting pictures, Eakins devoted the remainder of his career to portraiture. Since he rarely received commissions, most of his sitters were family, friends, and professionals he admired. He portrayed creative and intellectual individuals, such as musicians, scientists, doctors, teachers, poets, and artists. Rather than idealizing his sitters’ appearances, he painstakingly represented their facial features, aging skin, and bone structures. Depicted in isolated settings with closed mouths, searching eyes, and tilted heads, his subjects appear as though they are in deep introspection. The most well known of these psychologically penetrating portraits is The Thinker (1900), which features Eakins’s brother-in-law, Louis N. Kenton.

Legacy

Although Eakins sold fewer than thirty paintings and only had one solo exhibition in his lifetime, having lost prestige when he left PAFA, he exerted an incredible influence upon his students, many of whom became renowned artists. Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937) gained an international reputation for his religious paintings. His studio assistant and close friend Samuel Murray (1869-1941) developed a thriving career as a figurative sculptor. Eakins also taught the realist painter Thomas Anshutz (1851-1912), who became the head instructor at PAFA in 1909. Dedicated to the study of anatomy and perspective, Anshutz passed down Eakins’s techniques and devotion to the human figure to those who became the leaders of the next generation. He most notably taught the forerunners of the Ashcan School: Robert Henri (1865-1929), John Sloan (1871-1951), George Luks (1867-1933), Everett Shinn (1876-1953), and William Glackens (1870-1938). Eakins’s teaching methods and subject matter served as a model for students in the Philadelphia region long after he left PAFA.

It was not until after Eakins’s death that scholars and critics began to recognize his role in the history of American art. Goodrich’s 1933 biographical study was instrumental in drawing attention to Eakins’s unwavering, almost scientific devotion to the representation of the human body. By mid-century, Eakins had not only become a source of pride for Philadelphia but also a celebrated figure in the canon of American art history, widely praised for his meticulous working methods, portrayal of everyday life, and influential, though controversial, teaching strategies. Considered one of the greatest American artists, he is represented in the collections of major museums across the country.

Michelle Donnelly is a Curatorial Fellow at the Whitney Museum of American Art. She earned her M.A. in Art History from the University of Pennsylvania in 2014 and worked as a Curatorial Assistant at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts from 2013 to 2014. (Author information current at time of publication)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University