City of Medicine

Essay

In 1843, a student at the “med school of the University of Pennsylvania,” as he called it in a letter to a friend in Boston, declared Philadelphia “decidedly the city of the Union for doctors, the facilities for study making it a perfect little Paris.” The comparison reflected the renown of the French capital at that time for bedside teaching and anatomical dissection. By that point in the mid-nineteenth century, Philadelphia had become the country’s pre-eminent medical city, known particularly for its wealth of opportunity for medical education. Although the city lost its edge in the early 1900s, it recovered later in the century to become a growing center of health care, research, and education. Medical care and education remained integral factors in the social and economic fabric of the city.

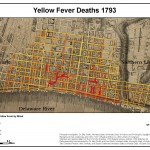

Philadelphia gained its early reputation as a city of medicine through the development of hospitals and medical schools. The founding of Pennsylvania Hospital in 1751 (America’s first general hospital) was an indication that by the mid-eighteenth century, Philadelphia had grown into a substantial urban complex with needs for services beyond what family and church could provide. Founded by physician Thomas Bond (1712-84) and Benjamin Franklin (1706-90), the nation’s first hospital joined a movement—rooted in Enlightenment thought, then underway in Britain—to create “voluntary hospitals” to care for “strangers” and the “worthy poor,” funded and conducted by private philanthropy. From the outset, the hospital contributed to the city’s allure in medical education. Its Wednesday and Saturday morning demonstration “clinics” drew crowds of nineteenth-century medical students.

Numerous hospitals subsequently arose within neighborhoods and nearby townships, supported by religious denominations or particular segments of the citizenry, such as African Americans or women. The city opened Blockley Almshouse in 1732, which later became Philadelphia General Hospital; and the origins of the Municipal Hospital for Contagious and Infectious Diseases can be traced to before 1818. Specialty hospitals arose for care of the eyes, children, and maternity work. Reflecting the Quakers’ concern for those “deprived of reason,” Pennsylvania Hospital spawned a progressive Hospital for the Insane (1841) on then-rural grounds west of the city; a Friends Asylum (1817) was founded in the Frankford countryside. With other Quaker women, in 1862 pioneer woman doctor Ann Preston (1813-72) founded Woman’s Hospital of Philadelphia to provide clinical training for women medical students and nurses. Temporary hospitals, some immense, were thrown up throughout the city to care for soldiers during the Civil War, the Satterlee in West Philadelphia being the best known. Eventually the city’s medical schools established their own hospitals.

The numerous hospitals served as objects of neighborhood pride and philanthropy, particularly service by women. In addition, their accident wards supported the city’s vast industrial growth in the nineteenth century.

Philadelphia’s place as a center of medical education can be traced to 1762 when William Shippen Jr. (1736-1808), son of a physician and educated in England and Edinburgh, initiated some lectures on anatomy and midwifery on Walnut Street near Third. Also a product of Edinburgh and European experience, the energetic John Morgan (1735-89) in 1765 proposed an enlightened plan for medical education, and with Shippen, inaugurated lectures at the College of Philadelphia intended as part of a course of study leading to a degree in medicine. From 1789 through 1791, both the revived College of Philadelphia and the newly chartered “University of the State of Pennsylvania” offered medical lectures, by feuding faculties (Philadelphia’s early teaching physicians were a notably feisty bunch). The factions united as the forerunner of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, America’s first. It won standing during the nineteenth century as one of the strongest in the nation, though strong in a stolid sort of way.

Perceiving room for another medical school in Philadelphia, if not an actual need, surgeon George McClellan (1796-1847) and some collaborators opened Jefferson Medical College in 1824. Both Penn and Jefferson welcomed huge classes, and so produced a high proportion of early American doctors. Jefferson’s faculty came to rival Penn’s in national reputation.

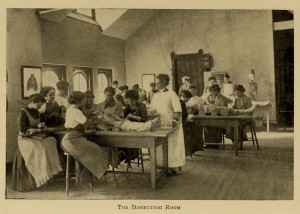

Beginning in the 1840s and 1850s, in Philadelphia (and elsewhere in the United States), the making of new medical colleges swelled into a kind of mania. Those after Penn and Jefferson that endured into the twentieth century included Hahnemann Medical College (1848); the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (1850; the first of its kind in the world); the Medico-Chirurgical College (1881); the Philadelphia Polyclinic and College for Graduates in Medicine (1883); and the Philadelphia College and Infirmary of Osteopathy (1899). Other schools, ranging from fully creditable to entirely fraudulent, came and went. Extinct schools included (among many) the co-educational Penn Medical University (1853), which had nothing to do with William Penn and was surely not a university. Lastly, the Medical Department of Temple College, later Temple University School of Medicine, opened in 1901. The availability of strong medical education for women, and the presence of several women’s hospitals, fostered growth of a sizeable community of women physicians and surgeons who practiced and taught here. Hahnemann Medical College taught the therapeutic system of German physician Samuel Hahnemann (1745-1843) called homeopathy, which flourished in Philadelphia.

By 1890, about 2,000 names appeared in the city’s medical directories, for a population of approximately one million. Most were doctors in the neighborhoods—serviceable, often hard-working. They saw patients in their homes and during office hours, and some attended at a hospital. They looked after illnesses severe and trivial, delivered babies, vaccinated, repaired fractures and lacerations, gave advice; and, more or less successfully, made a living.

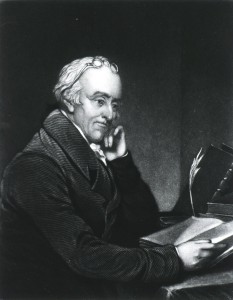

But it was the downtown physicians and surgeons, most with senior faculty positions at Penn or Jefferson, who built Philadelphia’s reputation as the nation’s medical capital. Among the early figures were Benjamin Rush (1749-1813), a reformer interested in everything, concerned with better care of the insane, and signer of the Declaration, recalled (unfortunately) for his ferocious use of mercury and bleeding for yellow fever; Philip Syng Physick (1768-1837), “father of American surgery”; and editor and ophthalmologist Isaac Hays (1796-1879). Later in the nineteenth century came anatomist and brilliant polymath Joseph Leidy (1823-91); master teacher of internal medicine Jacob Mendez Da Costa (1833-1900); physiologist, neurologist, psychiatrist, and popular novelist S. (Silas) Weir Mitchell (1829-1914); internationally known surgeons Samuel D. Gross (1805-84), and W.W. (William Williams) Keen (1837-32), the latter very much a progressive mind and a teacher at Woman’s Medical, Jefferson, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (anatomy). Gynecologists included Washington L. Atlee (1808-78), among the first to remove uterine fibroids, and Emeline Horton Cleveland (1829-78), one of the earliest women to perform abdominal surgery. Others gained repute through specialty practice centered on disorders of the eye, ear and throat, skin, nervous system, and mind. Active as well were oddballs and dissidents–followers of arcane sectarian systems, or the radical Quakers from Bucks, Montgomery, and Chester Counties who upheld the right of women to study medicine.

![Progressive surgeon W[illiam] W[illiams] Keen (1837-1932), a graduate of Central High School, taught at the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania and later at his medical alma mater, Jefferson Medical College. He advocated laboratory research and accepted the germ theory. Keen also counts as a pioneer in neurological surgery and collaborated with S. Weir Mitchell (1829-1914) in studies of nerve injury acquired during the Civil War. He also taught anatomy at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. (National Library of Medicine)](https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/WW-Keen-224x300.jpg)

It was not, of course, novels or Arctic ice that established the stature of Philadelphia doctors in the nineteenth century. What then? One can extrapolate from what the distinguished anatomist and historian George W. Corner (1889-1981) wrote about the senior faculty at Penn: “The University’s medical teachers had always been superb clinicians—masters of diagnosis and treatment and polished expositors.” That is, they brought comprehensive knowledge and experience to their practices and teaching (and many were broadly erudite beyond their professional expertise).

For most of the nineteenth century, medical practice drew upon the foundational sciences of anatomy and morbid anatomy (pathology, the study of structural change in organs caused by disease). Philadelphia’s skilled anatomists dissected, taught, and wrote books that added to the city’s reputation as a city of medicine. Several brought back the ideas and methods they had studied in Paris. The reputations of Philadelphia’s doctors spread through their participation in national organizations, consulting or teaching visits out of town, and the praise of their students. They benefited from Philadelphia’s centrality in medical publishing: its enormous production of medical books in the nineteenth century far exceeded that of New York or Boston. Philadelphia physicians readily fed the publishers’ demands for new textbooks and manuals (including homeopathic). For more than 100 years, the American Journal of the Medical Sciences, edited and published in Philadelphia, prevailed as the country’s leading such periodical.

In the early twentieth century, however, Philadelphia lost its edge. Significantly, the influence of Philadelphia’s American Journal of the Medial Sciences declined, while the New England Journal of Medicine, published in Boston, gained scriptural standing. Not only Boston but also New York and Baltimore challenged Philadelphia for medical leadership of the United States, and in some ways won. The destabilizing factor was experimental laboratory research—or, unhappily for the Quaker City, the paucity of it in the city’s medical colleges. The decisive factor was philanthropy—or the paucity of it for Philadelphia’s medical colleges.

By the 1880s and 1890s the center of advance in medical science had shifted from the hospital wards and autopsy rooms of Paris to the universities and laboratories of Germany. Beginning in the 1860s and 1870s, the acceptance of microbes as the cause of many diseases leant enormous luster to the laboratory and its workers. Physiology, the study of function, seemed a promising field. A handful of young American medical graduates worked under German scientists in the 1880s and 1890s, then returned home to seek a place to do original laboratory research. The only likely locus in Philadelphia in this period was Penn, but it was not to be. One of these German-trained men, Simon Flexner (1863-1946), came to the university in 1899 but left in 1903, disappointed by the lack of interest and resources for investigation. He went to New York to head the new Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research. In a history of Penn’s medical school, George W. Corner wrote that in this period its leaders failed to recognize that “for a generation and more to come, the advance of medicine was going to depend on discoveries in biology and biochemistry that would rapidly alter the physician’s whole outlook.” Corner might have added physiology and bacteriology. It was indicative of local inertia that neither Jefferson nor Penn required course work in bacteriology until ten years after Robert Koch (1843-1910) in Germany announced the discovery of the microbe causing tuberculosis.

Aware of the need to move forward, progressive leaders at the Penn medical school in 1910 effected a reform program (really a coup), which promoted David Edsall (1869-1945), an alumnus and faculty member with sound credentials in both laboratory and clinical work. The insurrection displaced several senior professors and brought in promising researchers from outside the city. Regrettably, the “old guard” among faculty managed a counter-revolution: Edsall left Penn and soon guided the rise of Harvard University Medical School to pre-eminence.

Perhaps these events reflected the larger intellectual outlook of Philadelphia in the nineteenth century. Never as overtly concerned with pure knowledge as Bostonians, Philadelphians excelled in the realm of the useful and tangible: mechanical innovation and making things well, illustration and lithography, architecture and building, and the practice of medicine and surgery. Unlike at Harvard and Yale, at Penn the science, engineering, and medical schools occupied most of the space. Of course erudition and scholarship could be easily found in the city, but for the most part, the practical prevailed. The leading nineteenth-century physicians and surgeons of Philadelphia did publish a great deal that was new—careful anatomical and pathological observations, discerning descriptions of diseases, novel procedures and remedies. But animal experimentation in the laboratory seemed foreign.

As medical science advanced in Boston under Edsall, several accidents of philanthropy favored the ascent of Baltimore and New York City as national centers of medical education and research. In the nineteenth century, Americans saw medicine as practical work and a source of livelihood and thus not as an object of charitable support. Neither government nor individuals subsidized medical research. Few Philadelphians made donations to the city’s medical schools. (A modest exception was the Woman’s Medical College, embraced by its Quaker friends.) Nor did this usually occur elsewhere. But in Baltimore, Quaker businessman Johns Hopkins unexpectedly bequeathed his immense fortune to the founding of a hospital and a university. The early trustees chose to build the university on the German research model, including a medical school linked to the hospital. The Johns Hopkins Medical School opened in 1893—with former Philadelphian William Osler (1849-1919) as one of its prized founding faculty.

In 1910 the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, founded in 1905, in conjunction with the Council on Medical Education of the American Medical Association, engaged educator Abraham Flexner (1866-1959), Simon’s brother, to carry out an inspection of North American medical schools. Flexner’s famous report of 1910, Medical Education in the United States and Canada, furthered a process already underway to raise standards and close marginal, or worse, schools. Subsequently, Flexner directed the distribution of grants from the Rockefeller General Education Board to the stronger schools. Dogmatic and sometimes arrogant, Flexner insisted on the “full-time plan” (essentially, that medical school teachers be on salary, not mainly in private practice); nurturing of research; and assured access to hospital teaching beds. His vision also demanded a continued reduction in the number of medical schools in the United States, with no more than one school, fully part of a university, in each metropolis.

Neither “full-time” for clinical faculty nor the giving up of schools much appealed to medical Philadelphia, where at each older institution a distinct personality and heritage had evolved, upheld by alumni, faculty, and even students. For a time, however, Penn and Jefferson diligently worked towards a merger, or at least an awkward sort of coupling that would perhaps look like a merger to Flexner, but still preserve individual identities. The press touted the plan: “Philadelphia is now in a fair way to become a contender for the title of the medical center of America” said the Philadelphia Press on June 3, 1916—tacitly admitting that the city already had lost such status (other newspapers agreed). The unlikely merger plan dissolved in 1917, and with it, the expectations for major foundation funding. By 1920, the Carnegie and Rockefeller philanthropies had contributed approximately $80 million for the development and endowment of American medical schools. None of this money came to Philadelphia.

Although some meaningful local gifts aided the city’s medical schools in this period and Philadelphia surely had wealth, no one in the city matched John D. Rockefeller. The largest single act of philanthropy aimed at education was by banker Anthony J. Drexel (1826-93), whose admirable creation of the Drexel Institute for Art, Science and Industry (now Drexel University) in 1893 centered for the most part on providing affordable practical education matched to the industrial needs of the city and the age. An assessment of Philadelphia philanthropy from 1893 praised Drexel, while declaring that the city’s millionaires tended to send their dollars far away–to “famine stricken Russians,” the “red man on the frontier,” and, generally, to “the dark and hidden places of the earth.”

A sampling of the leading journals of experimental work in medicine in the mid-1920s reveals that although Philadelphia sent forth a few papers, Boston, Baltimore, and New York generated substantially more. The earliest American medical scientists to win Nobel prizes in physiology or medicine included researchers at the Rockefeller Institute in New York and Harvard Medical School in Boston, but none from Philadelphia. Of course, the city’s medical fabric was not entirely dormant. Sound scientific work developed in microbiology and in some of the stronger “basic science” departments of the medical schools. In the early 1920s, A. Newton Richards (1876-1976) at Penn, who as a young imported pharmacologist-physiologist managed to survive the counter-revolution of 1910, carried out with colleagues brilliant studies of the function of the kidney. In doing so, he attracted some of the city’s earliest research support from a foundation, the Commonwealth Fund.

Philadelphia’s opportunity for a medical revival came in the 1950s. A flood of research support which appeared from the National Institutes of Health (and other governmental funding) led to, if not a leveling, at least considerable opportunity for all of Philadelphia’s medical schools, and some hospitals, to expand their clinical services and increase research productivity. Soon the schools swelled into “academic medical centers,” keenly competing with each other while looking more and more like each other. Woman’s Medical admitted men, and Hahnemann ejected Samuel Hahnemann’s homeopathy, as it made an astonishing transformation from minute doses (a tenet of this practice) to a skyscraper stacked high with intensive care units. In the absence rational planning based on needs of the citizens, many of the old neighborhood hospitals became poor and closed, while a corridor of high-tech clinical centers—Pennsylvania Hospital, Jefferson, Hahnemann/Drexel, Penn, Presbyterian—formed an imposing east-west alignment downtown. Temple to the north struggled valiantly with the burdens of caring for the sick and shot-up poor, as did the surviving hospitals in deteriorating districts. Beyond the city’s borders, some of the larger community hospitals, such as Lankenau and Abington in the suburbs and Cooper in Camden, expanded their educational functions and established successful research programs. All of this growth created jobs for nurses, physicians, scientists, technicians, billers and coders, and more, and required the ceaseless construction of buildings and additions. The United States Bureau of Labor Statistics documented “education and health services” (combined in its statistics) as the region’s largest employment supersector.

Even in the period of decline in the early decades of the twentieth century, Philadelphia’s medical institutions never lost their reputation for the highest quality training of medical students, residents, nurses, and pharmacists; in fact, the attraction grew as the major centers expanded. By the later decades of the twentieth century, “health care” and health-care education became the region’s dominant industry. White coats, short and long, continued as an enduring visible attribute of the city and region.

Steven J. Peitzman is Professor of Medicine at Drexel University College of Medicine. His historical work includes the book A New and Untried Course: Woman’s Medical College and Medical College of Pennsylvania, 1850 – 1998 (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2000), and articles about medicine and medical education in Philadelphia and Germantown. (Author information current at time of publication.)