Art of Dox Thrash

Essay

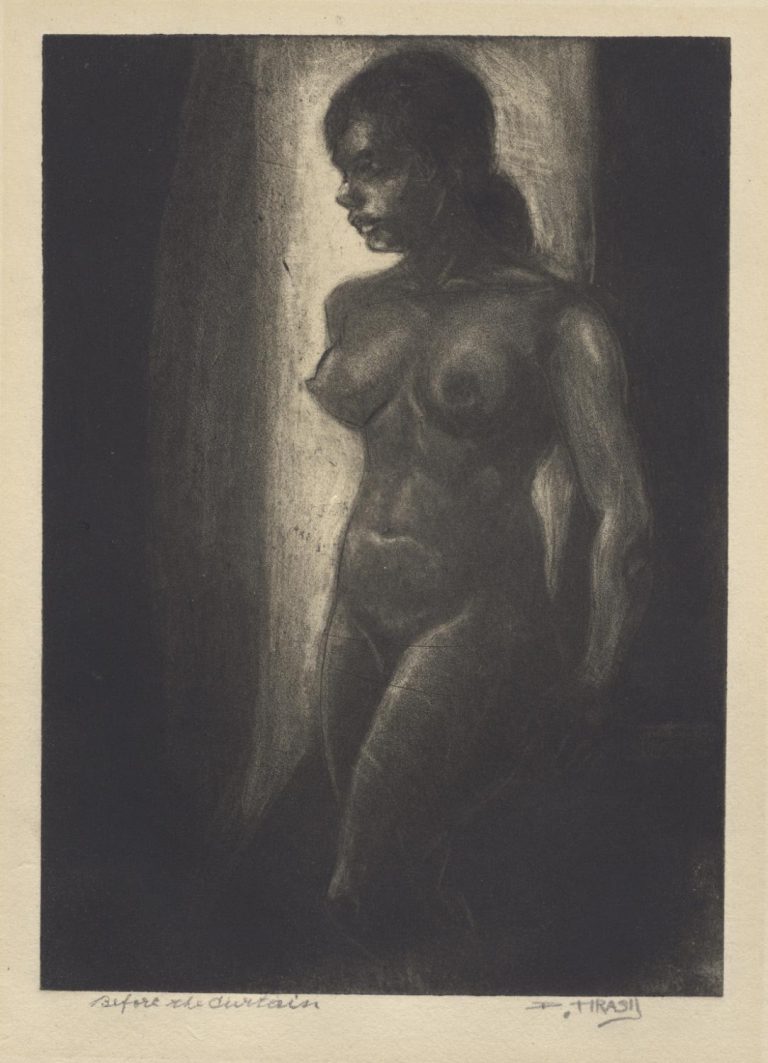

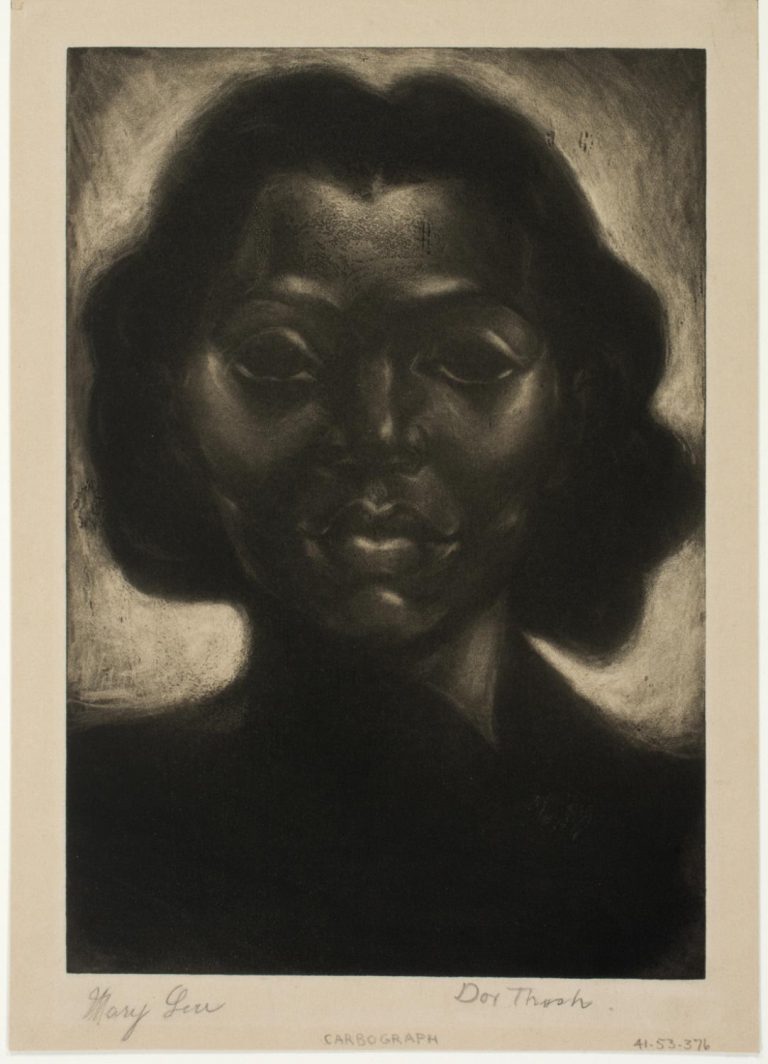

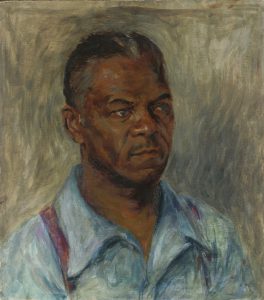

Dox Thrash (1893-1965) was an accomplished draftsman, printmaker, watercolorist, and painter, whose art reflected his experiences as an African American in Philadelphia. He became well known in the 1940s after developing the Carborundum printmaking technique at the Philadelphia Fine Print Workshop (311 Broad Street) of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project. By rubbing coarse Carborundum crystals onto a metal plate with a heavy flatiron, he created prints with dense blacks, smooth, sculptural forms, and velvety textures. His dignified representations of African Americans in his portraits, genre scenes, nude studies, and landscapes deeply resonated with the Black community in Philadelphia and earned him national acclaim.

Born in Griffin, Georgia, Thrash settled in Philadelphia in 1925 to pursue his lifelong ambition to become an artist. He had first studied art by taking correspondence courses as a teenager. In 1914, he enrolled in evening classes at the Art Institute of Chicago. His studies were interrupted in 1917 by the U.S. entry into World War I. After serving in the army for fourteen months in an all-Black unit known as the Buffalo Soldiers, Thrash resumed his art education in Chicago. Eligible for government funding because of his war service, he registered as a full-time student for the first time in 1920. Over the next three years, he studied painting, drawing, mural design, commercial art posters, lettering, and decorative composition. He also received private tutoring from William Edouard Scott (1884-1964), a distinguished African American painter and muralist. Thrash then worked part-time jobs and drew portraits in Boston, Connecticut, and New York before finding work as a commercial artist in Philadelphia. He designed posters for the American Interracial Peace Committee, which held an annual Negro Music Festival, and the Tra Club, a cultural center founded by African American artists.

Accomplishments in Printmaking

Thrash developed his skills as a printmaker under the guidance Earl Horter (1880-1940) at the Graphic Sketch Club (which in 1944 became the Samuel S. Fleischer Art Memorial, located at 719 Catharine Street). There, he mastered a variety of techniques, including etching, aquatint, drypoint, mezzotint, lithography, and linoleum cut. He enjoyed experimenting, often combining several processes in one print and reworking his plates to create unique impressions.

In 1937, Thrash joined the Philadelphia Fine Print Workshop. His investigations of materials and techniques led him to invent the Carborundum printmaking process. With the help of colleagues Hugh Mesibov (b. 1916) and Michael Gallagher (1898-1965), he discovered that roughening the surface of a copper plate with Carborundum, a gritty industrial substance normally used to prepare lithographic stones, produced a wide range of rich tones and smoothly modeled forms. Thrash coined the prints he created “Opheliagraphs” in honor of his mother.

Thrash’s innovations in printmaking brought him widespread acclaim. Over the next two decades, he became a prominent artist in the Philadelphia region, exhibiting his work at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Print Club of Philadelphia (the Print Center, 1614 Latimer Street), and Philadelphia Art Alliance (251 S. Eighteenth Street). His strongest support came from the Pyramid Club (1517 W. Girard Avenue), a Black cultural society that included his work in its annual exhibitions and introduced him to an influential network of artists, curators, critics, and dealers.

African American Community

Thrash’s reputation quickly grew outside of the Philadelphia region. Beginning in the late 1930s, he participated in landmark exhibitions of African American art across the country. The philosopher, writer, educator, and leader of the Harlem Renaissance Alain Locke (1885-1954) selected his prints for the exhibitions Contemporary Negro Art at the Baltimore Museum of Art in 1939, Art of the American Negro (1851-1940) at the Chicago Coliseum in 1940, and American Negro Art, 19th and 20th Centuries at the Downtown Gallery in New York in 1941. His work was also displayed in Chicago in the 1941 inaugural exhibition at the South Side Community Art Center, a racially diverse workshop run by the Federal Art Project. The following year, he had a solo exhibition of his graphic art at the historically Black college Howard University in Washington, D.C.

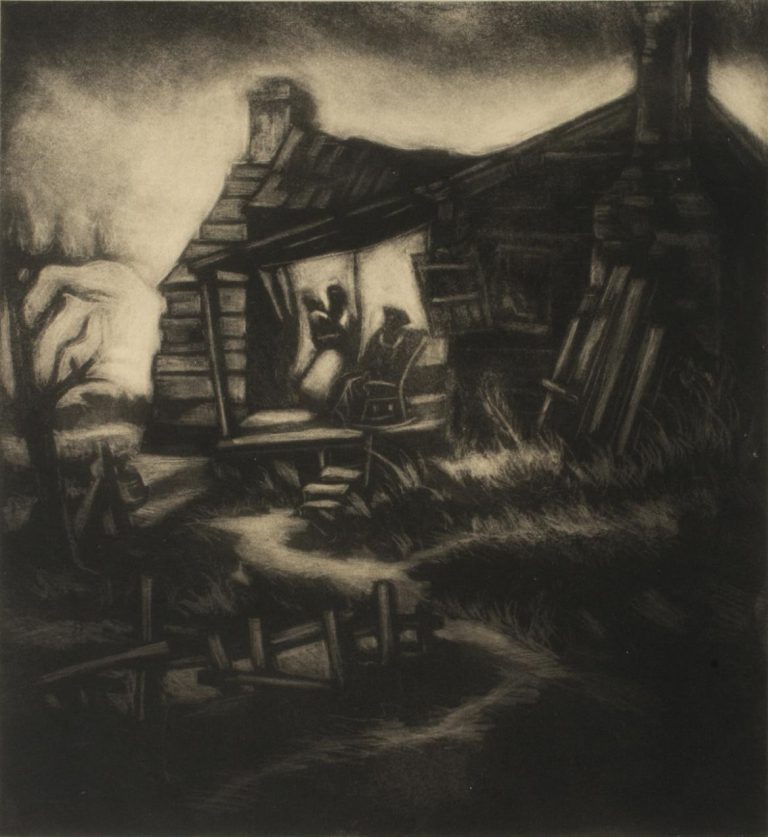

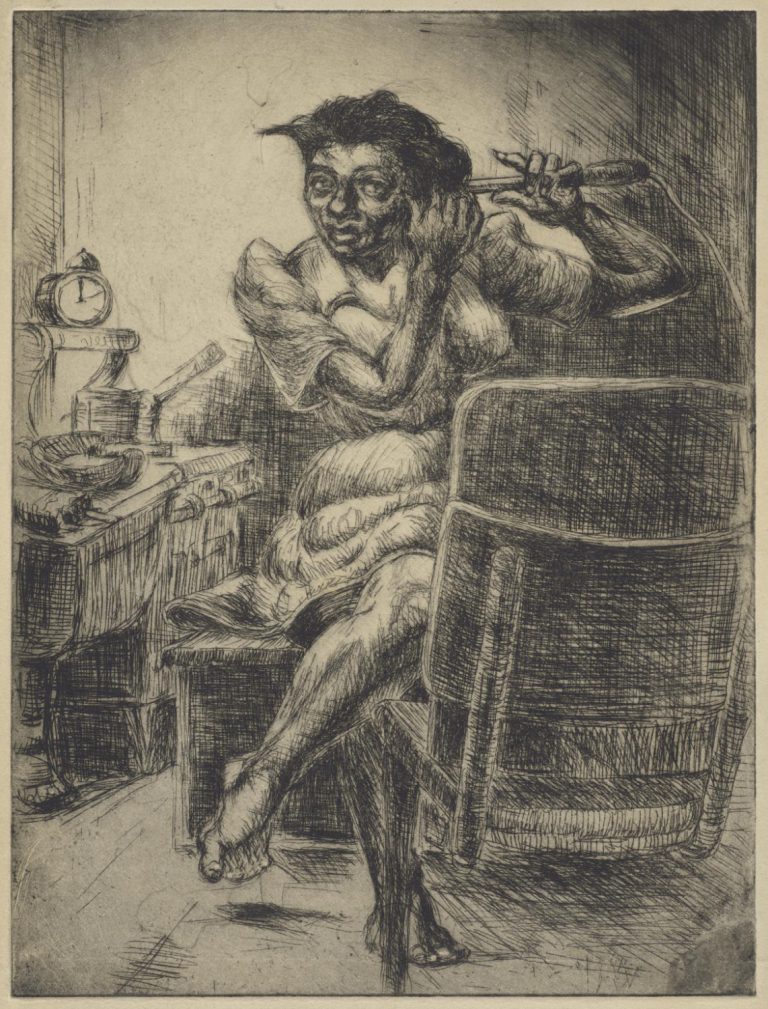

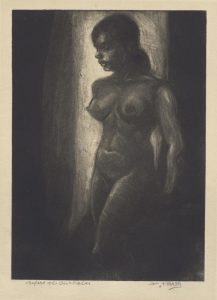

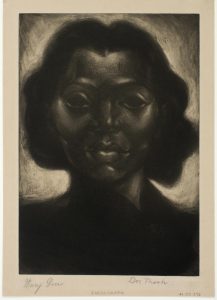

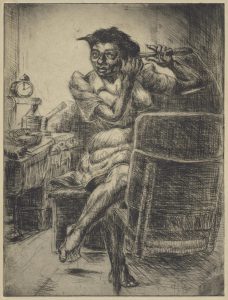

Thrash earned praise not only for his technical innovations but also his sympathetic representations of African Americans. As art historian Kymberly N. Pinder has noted, his art participated in the shaping of a positive Black identity, as put forth by Locke and sociologist, writer, and educator W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963). Challenging negative representations of African Americans as grinning buffoons that had circulated in mass visual culture since the nineteenth century, Thrash created sensitive, compelling portrayals of Black individuals in a variety of media. His portraits, character studies, and genre scenes, such as Mary Lou (c. 1939-40), Second Thought (1939), and Saturday Night (c. 1942-45), depict Black subjects with a sense of dignity and strength. Thrash also produced rural and urban landscapes that featured Black actors. Prints such as Cabin Days (c. 1938-39) allude to his southern upbringing. Others, such as Freight Yard (before 1943), focus on Philadelphia industries, in dialogue with the art of the Social Realists of the 1930s and 1940s.

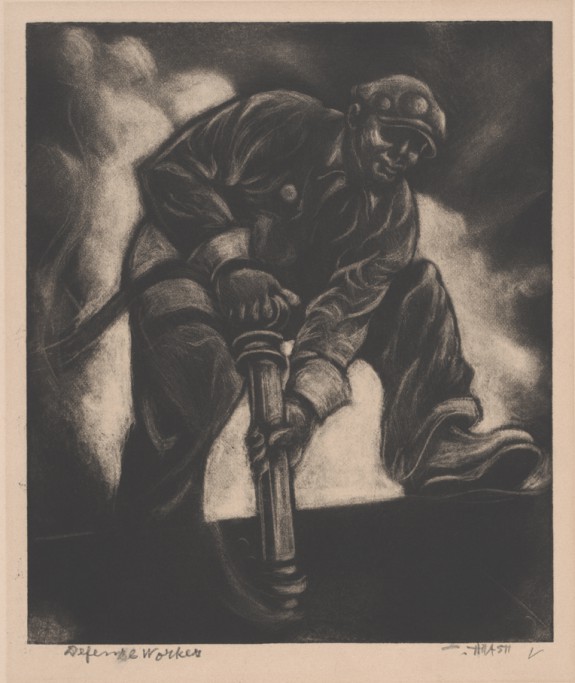

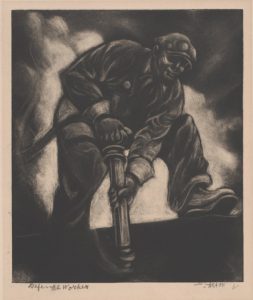

Thrash began to focus more strongly on Black laborers during World War II when African Americans faced widespread discrimination in the rearmament program. Although he was a proud veteran, he was denied employment at the Philadelphia Navy Yard in 1942 because of his race. Prints such as Defense Worker (c. 1941) feature self-motivated Black men productively contributing to the war effort. From his portraits to his genre scenes to his cityscapes, Thrash’s wide-ranging subject matter addressed pertinent issues faced by African Americans.

Thrash remained active in the Philadelphia art scene until his death in 1965. Despite the national attention the Carborundum technique achieved during his lifetime, it failed to be embraced by artists outside the Philadelphia Fine Print Workshop. The seminal 2002 exhibition Dox Thrash: An African American Master Printmaker Rediscovered organized by the Philadelphia Museum of Art brought renewed attention to Thrash’s inventive approaches to printmaking and the salience of his subject matter to the Black community of his era.

Michelle Donnelly is a Curatorial Fellow at the Whitney Museum of American Art. She earned her M.A. in Art History from the University of Pennsylvania in 2014 and worked as a Curatorial Assistant at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts from 2013 to 2014. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University