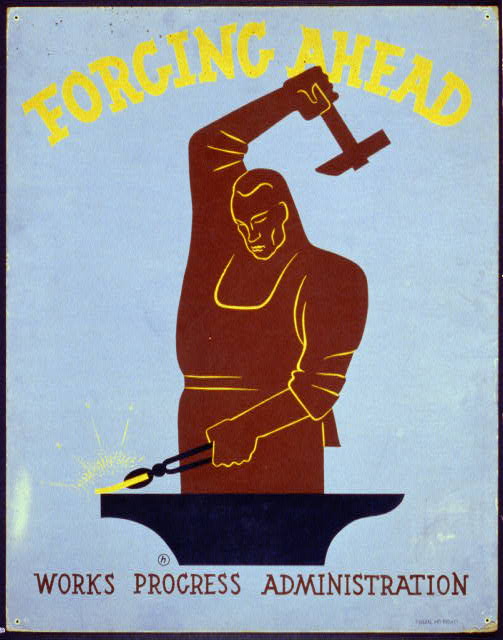

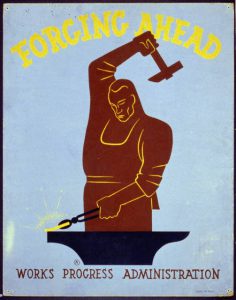

Works Progress Administration (WPA)

Essay

In response to the rising tide of unemployment nationally, and after the short-lived Civil Works Administration (CWA) failed to stem that tide, Congress in May 1935 created the Works Progress Administration (WPA), one of the “alphabet soup” of economic recovery programs enacted as part of the New Deal of President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945). Later called the Works Projects Administration, the job-creation program aimed to employ 3.5 million men and women throughout the nation, especially those living in Depression-wracked urban areas such as Greater Philadelphia. Inevitably, in Philadelphia as elsewhere, critics charged that the program was steeped in politics.

With a congressional appropriation of $4.8 billion dollars, the WPA sought to find useful jobs for the able-bodied unemployed as an alternative to the demeaning, psychologically and physically debilitating “dole” (public welfare). Moreover, WPA monies were to go into workers’ paychecks, not to be spent on materials, which would be covered by states or municipalities.

On the eve of the WPA’s creation more than ninety-three thousand needy families, many of them jobless, relied on the Philadelphia County Relief Board (CRB) for relief. Nearby industrialized cities such as Camden, New Jersey; Chester, Pennsylvania; and Wilmington, Delaware, also suffered. In Camden, per-capita annual income fell from $839 to $433 between 1929 and 1933, and the New Jersey Emergency Relief Administration shut down in 1936 for want of funds. Philadelphia’s suburban counties such as Montgomery and Bucks in Pennsylvania, being much less industrialized, endured only half the joblessness of the City of Brotherly Love.

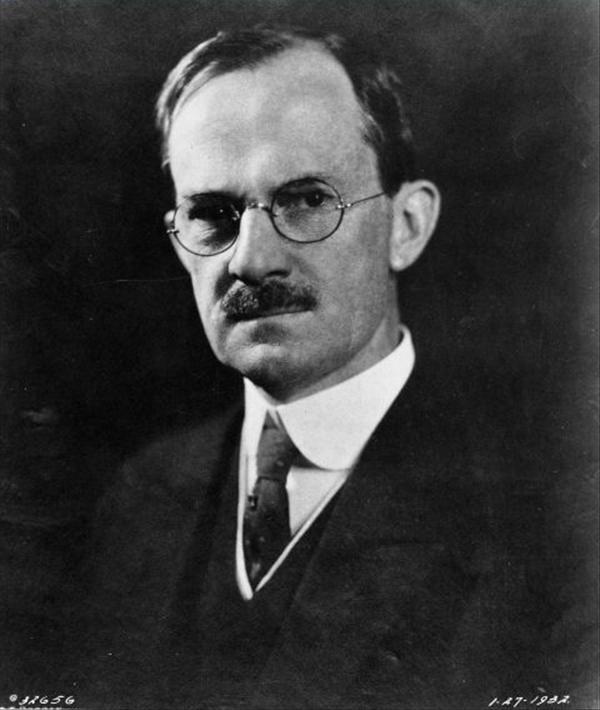

With harsh weather predicted for the winter of 1934-35, the New Deal launched the Civil Works Administration (CWA), which put jobless relief clients to work on a host of street, road, and park projects and on white-collar work especially in town and city halls. A CWA and WPA mattress project employed many women sewing and stuffing mattresses for transient camps and for poor families with incomes under $2,000 a year. But while labor leaders in Philadelphia cheered the CWA, the city’s Republican mayor in 1934, J. Hampton Moore (1864-1950), a devout fiscal conservative and apostle of retrenchment, refused any federal assistance monies in Philadelphia.

Resisting WPA

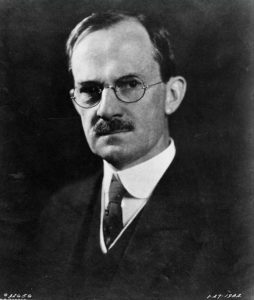

Moore just as adamantly barred cooperation with the WPA, which in June 1935 allocated $60 million to Philadelphia to employ seventy thousand jobless. By August fewer than thirty-five thousand Philadelphians had been enlisted through the program to build city schools and work at the Philadelphia Navy Yard and in jobs outside the city in Montgomery, Chester, and Bucks Counties. It was not until December 1935 that Moore atypically approved two large WPA projects, one to pave city streets and the other to vastly improve the city’s airport at Hog Island. Founded in 1927 as the Philadelphia Municipal Airport, the facility became the S.D. Wilson Airport after the WPA modernized it by adding a terminal, and later became the Philadelphia International Airport.

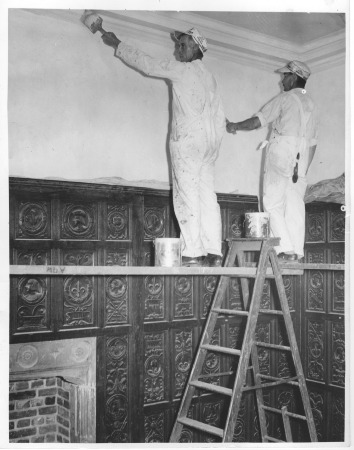

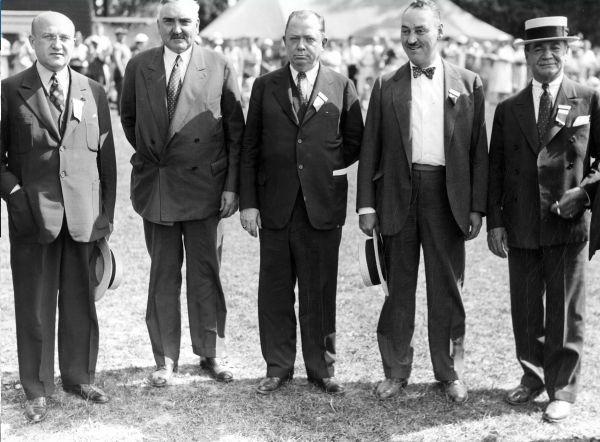

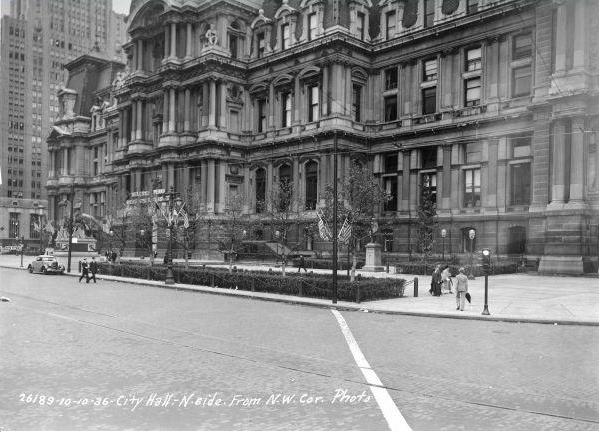

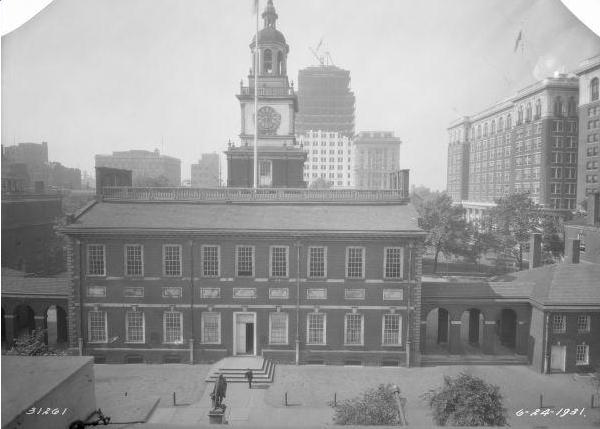

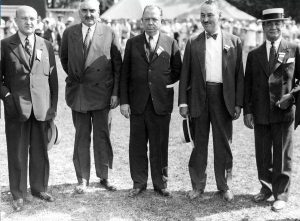

In contrast to Moore, S. Davis Wilson (1881-1939), a former Republican elected city controller in 1933 and mayor in November 1935 as candidate of the Fusion Party, made cooperation with the WPA his first priority. Wilson determined to use the WPA to employ eighty-five thousand jobless city residents. Indeed, as his first act as mayor Wilson rushed to Washington, D.C., to secure for Philadelphia the 1936 Democratic Convention and WPA projects to clean both City Hall and Independence Hall. In August he returned to Washington to wheedle $100 million from WPA Administrator Henry L. Hopkins (1890-1946) for street paving, waterworks, sewers, schools, parks, and a range of white-collar jobs such as compiling records of all delinquent water rents in the city for the previous fifty years.

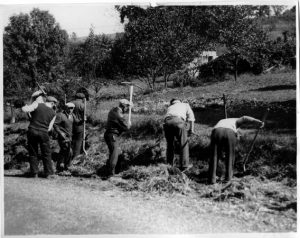

In terms of miles of paved streets, numbers of new schools, post offices, parks, and playgrounds, the WPA together with the Public Works Administration (PWA) and Civil Works Administration (CWA) transformed urban America. Still, in places like Philadelphia, Camden, Chester, and Wilmington, the WPA failed to fill its quota of jobs. Wilson had promised the city jobless eighty-five thousand WPA jobs, but by 1938 it employed scarcely forty-nine thousand. The problem? In Philadelphia, as elsewhere in a region suffering from lower property values and eviscerated tax revenues, municipalities proved unable or unwilling to allocate monies for materials. They were more likely to approve projects such as one for destroying poison ivy in Philadelphia parks that required no allocation. Philadelphia benefitted from thirty-seven sanitation projects between 1935 and 1938, most costing less than $50,000 in materials. Among fifty-five park projects of the same period that did require some allocation from either the state or an agency such as the Fairmount Park Commission, the WPA built thirteen stone and log trail shelters and comfort stations in Fairmount Park. In Pastorius Park it built an attractive rustic stone restroom. At the Philadelphia National Cemetery, WPA workers erected a rostrum in the form of a Tuscan-order Temple.

The WPA created work not only for jobless factory workers but also for the nation’s unemployed writers, musicians, and artists. Low-cost WPA white-collar projects employed relatively few people, but were numerous and popular. WPA art projects included a mural celebrating Philadelphia industrialism placed in the auditorium of Olney’s Finletter Elementary School. The youthful WPA artist Jackson Pollock (1912-56) created his “Male and Female,” later added to the collections of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Ahron Ben Shmuel (1903-84) created a WPA sculpture placed at the reptile house at the Philadelphia Zoo. As part of the American Guide Series the WPA Federal Writers Project employed jobless city white collar workers to create a series of guidebooks for states and cities, including Philadelphia: A Guide to the Nation’s Birthplace (1937).

Maintaining Streets

Large-scale, more costly projects proceeded with the sponsorship of the state or federal government. During the Great Depression Pennsylvania took over 145 miles of Philadelphia streets and maintained them with WPA assistance. In 1937 the WPA spent over $2 million on Philadelphia street projects. Another large-scale project added a rail line (later the PATCO high-speed line) across the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. One of Philadelphia’s largest projects employed women sewing garments and other goods to be distributed to the needy. Pennsylvania sponsored ten sewing room projects in Philadelphia between 1935 and 1938, the first costing $300,000, the second and largest costing $1.3 million. After 1937, as the threat of war loomed in Europe, projects to renovate and enlarge military installations topped the WPA’s list. Washington spent $500,000 to renovate Philadelphia’s Frankford Arsenal, $375,000 for the Navy Yard, and $109,000 to fireproof the magazine and improve roads at Fort Mifflin.

Nevertheless, the WPA failed to provide work sufficient to employ the mass of Philadelphia’s seventy thousand jobless families. A similar story prevailed in bankrupt Camden. Still, the region garnered a significant legacy of projects that helped Philadelphia, Camden, Chester, Wilmington and other urban places weather trying times. In Camden, for example, the WPA paved the city’s major Broadway thoroughfare, a project that provided the jobless 242 hours of labor and consumed four thousand tons of gravel and asphalt. The WPA also paved the city’s Federal Street and Haddon Avenue. In 1936 alone the WPA constructed Elijah Perry Park (replete with a swimming and wading pool), built Farnham Park, enlarged and improved Pyne Point Park, and constructed Roosevelt Plaza Park. Moreover, by uprooting rails from Camden streets and asphalting the resulting cavity, the WPA helped prepare the city and other urban areas for the end of trolley transportation and the coming age of urban bus transit. Likewise in Wilmington, the WPA undertook multiple waterworks projects, as well as major road projects, a number of which had begun with CWA. Among other Wilmington projects, the WPA improved the sewage system at all-Black Delaware State College, expanded the Rock Manor Golf Course, and with PWA and WPA replaced the city’s smaller Du Pont High School with a handsome neocolonial seventy-nine-room edifice.

Despite the effort to cast the WPA as “real” as opposed to “made” work, the WPA never escaped the stigma of “leaf-raking.” Nor did it escape the charge of being “political.” Until FDR’s reelection in 1936, when forty-two of the city’s fifty wards voted for the president, the Republican machine ruled Philadelphia. The election crushed the machine that had been led by William S. Vare (1867-1934). Seeking a scapegoat, Republicans found the WPA. Democrats never denied that politics infused the WPA. Hopkins conceded that it was impossible to expunge politics at the local level. Lorena Hickok (1893-1968), a journalist employed by Hopkins to report on economic circumstances around the country, exclaimed about the WPA in Philadelphia, “Oh, it’s plenty political alright; but the Republicans would do the same thing if they had the WPA.” Indeed, she reported, many Democratic committeemen in Philadelphia held WPA jobs and on election day “worked like hell at the polls.” Still, the legacy of the WPA’s beautiful parks, paved streets, modernized systems, and inspiring murals not only helped maintain and upgrade a languishing urban infrastructure but also kept thousands of families in Greater Philadelphia with modest but essential livelihoods.

John F. Bauman is Professor Emeritus of California University of Pennsylvania and Visiting Research Professor at the University of Southern Maine. He has written numerous books and journal articles on a broad range of modern urban policy issues. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright Rutgers University, 2017

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- A Better Pennsylvania, Produced by Pathe' for the WPA, 1937 (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Records of the Work Projects Administration (National Archives)

- Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration WPA (Art Story Foundation)

- America's Great Depression and Roosevelt's New Deal (Digital Public Library of America)

- New Deal Art During the Great Depression