Community Development

Essay

During the community development movement, which arose in the 1960s in large part in response to years of disruption spurred by government-imposed urban renewal, Philadelphia became an important center of activism and institutions devoted to locally-based improvement programs. Community development programs sought to provide greater control over the future of neighborhoods at a time when declining populations and tax bases were weakening municipal government’s capacity to deliver services and attract capital investment. The outcome of community development plans often depended on the extent to which government and community could agree upon sharing responsibility for making policy, developing programs, and allocating resources. These were especially difficult challenges in an era of scarce public resources.

Shared control over neighborhood development emerged in Philadelphia well before President Lyndon Johnson (1908-73) made “maximum feasible participation” a central component on his declared War on Poverty. Working in collaboration with the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority and the Philadelphia Housing Authority between 1952 and 1957, Friends Neighborhood Guild formed a housing cooperative devoted to advancing racial integration through the development of high-quality affordable housing in an impoverished community. It succeeded in both goals through the rehabilitation of nineteen deteriorated buildings in the vicinity of Eighth and Franklin Streets to create eighty-four new housing units. Subsequently it marshaled construction of Guild House, a 91-unit elderly housing complex located at 711 Spring Garden Street. Similarly, Bright Hope Baptist Church, working with a redevelopment plan approved by City Council in 1958, completed the design, organization, and marketing of 635 new single-family homes built in low-density style on 153 acres of land in North Philadelphia. Known as Yorktown, the new neighborhood helped create a base of middle-class African American homeownership in an area undergoing serious decline and clearance for the expansion of Temple University to the north and construction of public housing projects in West Poplar to the south.

Philadelphia became one of five cities funded in the Ford Foundation’s Gray Areas program, which piloted the federal War on Poverty’s Community Action Program. In 1962, the city formed the Philadelphia Council for Community Advancement (PCCA), to implement grants from Ford, the President’s Committee on Juvenile Delinquency, and later federal War on Poverty programs. Led by a coalition of public, labor, business, university, and African American civil rights leaders, PCCA initially focused on North Philadelphia, helping to establish and fund early housing and shopping center development by the Opportunities Industrialization Center, founded by the Rev. Leon Sullivan (1922-2001). PCCA went on to build cooperative and other affordable housing and support the growth of community development corporations around the city, though by the early twenty-first century its work became limited to housing counseling services devoted to helping homeowners avoid foreclosure.

Neighborhood-Based Organizations

Despite the shortcomings of the War on Poverty, not the least its Model Cities program instituted in 1966, the federal policy of ensuring “maximum feasible participation” prompted the creation of a number of community-based organizations. Among the first in Philadelphia and Camden, both called the Black People’s Unity Movement and both inspired by the Black Power movement, were self-help organizations determined to do more than simply serve as repositories for federal or other public funding. Not adverse to receiving public-sector support, these and other organizations, including Mantua Community Planners, Mill Creek Council, and Advocate Community Development Corporation, completed affordable housing ventures and operated a variety of health and human service programs in response to identified community needs. Such neighborhood-based organizations continued to contend, however, with unwanted effects of externally generated redevelopment during the late 1960s through the 1970s. Much of this opposition focused on the use of eminent domain to acquire private property and the associated displacement of residents and businesses. During this period, a number of additional groups formed to promote activism or to provide support for community-based initiatives.

Some of these groups organized exclusively to address a single issue. For example, a broad coalition of neighborhood-based organizations spearheaded a long-term campaign against the Crosstown Expressway proposal, a plan first introduced in 1947, which would have taken land between Lombard and South Streets to support the construction of a highway connector between the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers. The withdrawal of the expressway plans in 1974 was a milestone in the history of organized community activism in Philadelphia. Another highway revolt against the Vine Street Expressway and its planned ramps did not prevent the road’s construction but altered it and saved Chinatown. Across the Delaware River the prospect of a state prison on the waterfront prompted formation of Concerned Citizens of North Camden in 1978. Failing in the effort to block the prison, Concerned Citizens nonetheless moved from that defeat to create its own neighborhood plan and to secure the city’s acceptance for it.

Other groups formed to provide support for grassroots initiatives on a citywide basis. In 1969, the Philadelphia chapter of the American Institute of Architects founded the Architects Workshop, a program designed to provide planning and design services to community-based organizations. Largely supported by pro bono services contributed by private architectural firms and by VISTA volunteers working under the aegis of the War on Poverty during its early years, the program provided assistance to more than ninety community-based organizations annually during its most active period. The Philadelphia AIA withdrew from the program in 1977, though a group of architects revived its function in 1991, founding what became the Community Design Collaborative.

In 1973 activist Edward A. Schwartz (1943-2012) established the Institute for the Study of Civic Values in Philadelphia to promote civic engagement. The institute’s key role in supporting community development constituencies gained the organization citywide and, to some extent, national recognition and enabled Schwartz to win a City Council at-large seat in 1983. Similarly, in 1985 Camden residents formed a citywide organization, Camden Churches Organized for People, as a means of bringing neighborhood concerns to the attention of city government.

As population declined and the number of abandoned houses grew, groups of squatters moved into several hundred vacant buildings, primarily in North and West Philadelphia, during the late 1970s and early 1980s. The North Philadelphia Block Development Corporation, organized by activist T. Milton Street (b. 1941) in 1977, began assisting families in breaking into and moving into vacant houses that had been seized by the Department of Housing and Urban Development as a result of mortgage foreclosure. Street subsequently broadened the group’s approach to support squatting in city-owned and privately owned vacant houses, as a response to the inadequacy of city policies to systematically address property abandonment and the need for affordable housing.

As squatting gained momentum in Philadelphia, HUD Secretary Samuel R. Pierce (1922-2000) entered into negotiations with a leading squatter coalition, the Inner-City Organizing Network (ICON) and pledged to help squatters find housing in HUD-owned properties. In 1982, the City of Philadelphia began awarding funding to ICON to support housing rehabilitation activities, a practice that terminated when the organization found that role beyond its capacity.

Community Development Policy

Through something of a cruel irony, federal anti-poverty programs intended to spur community development were folded into a much broader and less targeted funding mechanism by Republicans under the name “community development.” With passage of the federal Community Development Act of 1974 funding previously associated with eight programs was consolidated into a single annual block grant award. With that change in policy, municipalities and counties gained broad discretion in determining how Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) funding would be allocated.

The 1974 Act mandated citizen participation in the planning and implementation of CDBG-funded activities and the convening of annual public hearings as a required part of the preparation of the CDBG funding proposal. To address these mandates, Philadelphia government staffed a Citizen Participation unit, convened a citizens’ advisory committee consisting primarily of representatives of neighborhood organizations, and created a CDBG budget line item for “community-sponsored projects.” In addition, the city allocated CDBG funding to support the operation of Neighborhood Advisory Committees, community-based organizations that, like the Project Area Committees formed in the urban renewal period, were created for the purpose of providing information about government-sponsored planning and development activities and encouraging grass-roots participation.

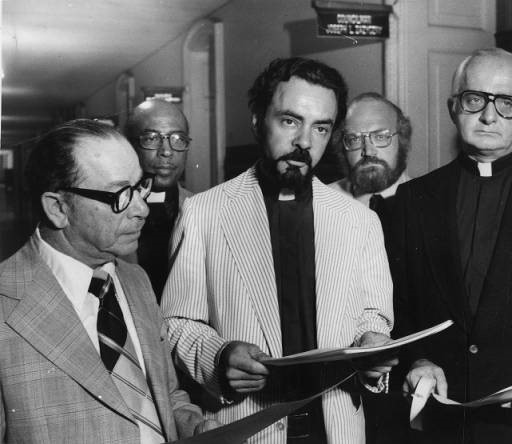

From the start of Philadelphia’s CDBG program, activists voiced significant concerns about the extent to which city officials would use their new discretionary powers in a manner responsive to their concerns and the extent to which external political considerations would influence decision-making about the allocation of CDBG funding. One response was the creation of the Philadelphia Council of Neighborhood Organizations (PCNO), a broad citywide coalition of community groups, founded in 1976 with the support of the Institute for the Study of Civic Values. The new coalition worked closely with the institute in advancing initiatives to make mortgages available in previously underserved neighborhoods, to address the city’s growing vacant housing problem, and to support city funding of neighborhood projects. Joseph M. Kakalec (1930-2007), a Jesuit priest who served as president of PCNO until 1982, played a key leadership role in convening and coordinating a coalition that was both broad-based and reflective of Philadelphia’s racial and ethnic diversity.

During the early years of CDBG program implementation in Philadelphia, activist groups such as the North Philadelphia Block Development Corporation joined with more established organizations such as the Housing Association of Delaware Valley to oppose CDBG funding decisions that bypassed neighborhood needs to support downtown development projects, police services, and public administration. This advocacy, ultimately supported by HUD administrators, resulted in a redirection of CDBG funds to provide more financing for affordable housing and community-based projects.

Affordable Housing Ventures

Although the National Housing Act of 1968 shifted government programs toward greater private sector control, two provisions—sections 235 and 236—opened the door to community participation. These provisions, through the Federal Home Administration, made mortgage insurance available to finance owner-occupied housing and rental housing, respectively. FHA insurance, combined with rental assistance subsidies obtained through the federal Section 8 voucher program, financed the production of many rental housing development ventures in Philadelphia neighborhoods. In a number of instances, these projects were organized in a manner similar to the Yorktown model, in which a private developer worked in partnership with a community-based organization or institution. Such was the case in West Philadelphia, where Mt. Olivet Senior Housing, a rental housing venture sponsored by Mount Olivet Tabernacle Baptist Church and Mount Vernon Manor Apartments, nurtured a collaboration between community members and the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority.

Several neighborhood-based organizations, assisted by consultants and service providers, also developed affordable housing as independent producers or as active participants in joint ventures with for-profit partners. National Temple Non-Profit Corporation, which developed more than three hundred apartments, townhouses, and single-family homes in North Philadelphia west of Broad Street, was the most productive of these groups.

Community Development Institutions

Many new opportunities for direct community engagement in real estate development and service delivery emerged in Philadelphia during the second term (1988-91) of Mayor W. Wilson Goode (b. 1938). Under the leadership of Edward Schwartz, the city’s Office of Housing and Community Development, the municipal agency created in 1976 to administer CDBG funding and other housing programs, financing and service contracts between the city and community-based organizations expanded significantly. In subsequent years, the agency made community development block grant funding available to support the completion of neighborhood strategic plans, to establish a citywide network of housing counseling agencies, and to create a systematic Request For Proposals approach for awarding development financing, in which first consideration would be given to proposals received from community-based organizations.

A primary boost to neighborhood-based development in the era of declining public resources was the formation of community development corporations (CDCs), which became the predominant community-based institution in the larger community development sector. Formed first in the mid-1960s as part of the War on Poverty, such organizations multiplied particularly in the Reagan era. Characterized by significant bonding capacities to draw neighborhood residents together in common purpose, they diversified their work from producing and managing affordable housing to engaging in workforce and commercial corridor development, community organizing, public health and food access, and various other projects and services. CDCs survived largely by marshaling external resources. These included not just government and philanthropic entities but the private sector as well. To further enhance their power to draw investment and desirable development to their neighborhoods, CDCs in Camden and Philadelphia joined to form their own associations devoted to presenting a unified voice in policymaking and budgetary circles.

Community development in Philadelphia and nationally has been supported by another set of important organizations, Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs), independent nonprofit organizations with their own sources of capital to reinvest in poor neighborhoods. A Philadelphia affiliate of the national Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) and a new organization, the Delaware Valley Community Reinvestment Fund (later renamed The Reinvestment Fund, or TRF), opened for business in Philadelphia in 1981 and 1985, respectively. Both organizations supported affordable housing ventures and other development and service programs in the region. They helped secure funds from the Low Income Housing Tax Credit program (authorized by Congress as an element of the Tax Reform Act of 1986), as well as the HOME Investment Partnerships Program (a component of the National Affordable Housing Act of 1990), among other sources.

Beginning in the late twentieth century, concerns about the effect of rising property values on housing affordability influenced some advocates to work toward the creation of community land trusts, organizations that would acquire real estate, sell existing or newly developed houses on the property at prices affordable to low- and moderate-income households and retain ownership of the land under them in order to help ensure that subsequent resale prices would be affordable as well. As one outcome of the late-1970s squatters’ movement, the North Camden Land Trust formed to manage the rehabilitation of vacant houses (assisted with financing provided by TRF) that were not in habitable condition. During the next decade, two land trusts formed in Philadelphia: United Hands Community Land Trust, organized by the Kensington Joint Action Council, and the ACORN-sponsored Community Land Association of Pennsylvania. Although these organizations were successful in rehabilitating vacant properties for affordable housing for a time, these initiatives were not able to overcome funding, organizational development, and capacity-building challenges in order to sustain operations over a longer term.

A Recharged Housing Market

During the years leading up to and following the advent of the twenty-first century, Philadelphia’s real estate market grew stronger, influenced in part by national trends and in part by the success of a ten-year tax abatement, offered as an incentive to developers, initially in Center City and subsequently on a citywide basis. By one estimate, Philadelphia house prices increased by more than 150 percent in nearly every section of Philadelphia between 1979 and 2015.

The revitalized real estate market, combined with shifts in federal funding away from housing for the poor, presented new opportunities and challenges for nonprofit and neighborhood-based organizations. Some leveraged private financing and entered into joint ventures with private developers. For instance, Project HOME purchased a nine-story apartment building near Rittenhouse Square and developed it for 144 units of mixed-income housing. The State Department authorized the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation to secure $33 million in financing through the federal EB-5 Immigrant Investment Program to support the development of Eastern Tower, a mixed-use high-rise development project at Tenth and Vine Streets, though the CDC abandoned its initial plans to include affordable housing in the project.

As property values rose, community development advocacy focused on housing affordability and on the inadequacy of the city’s policies for acquiring and conveying vacant property. Women’s Community Revitalization Project (WCRP) played a leading role in organizing coalitions to advance two related initiatives: the Philadelphia Campaign for Housing Justice, in support of an inclusionary zoning mandate that would require private developers to contribute a portion of their profits to an affordable housing fund; and the Campaign to Take Back Vacant Land, focusing on the creation of a Philadelphia Land Bank as a resource for stabilizing low-income communities. Philadelphia’s land bank legislation was approved in 2013.

The concept and institutions of community-based development owed much to the social and civil rights activism of the 1960s. Although limited in power, activists in many inner city neighborhoods in the Philadelphia area remained committed to assuring as much community control over development decisions as possible. Because poverty and inequality persisted in many high poverty neighborhoods in the region, their services remained in demand into the twenty-first century as they continued to seek revitalization through community empowerment.

Howard Gillette is Professor of History Emeritus at Rutgers-Camden and co-editor of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. Domenic Vitiello is Associate Professor of City Planning and Urban Studies at the University of Pennsylvania and an associate editor of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. This essay incorporates information gathered and compiled by John Kromer, former City of Philadelphia Housing Director and former Director of the Camden Redevelopment Agency. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Block grant provides school supplies for Camden and East Trenton students (WHYY, September 16, 2011)

- Will land bank put vacant lots to work in Philadelphia? (WHYY, February 3, 2012)

- 'Land bank' law expected to help reclaim blighted properties in Pa. (WHYY, October 29, 2012)

- Philly brokers deal to create land bank of vacant properties (WHYY, December 5, 2013)

- Wilmington credits federal money with providing more housing opportunities (WHYY,December 24, 2014)

Links

- Philadelphia Land Bank

- Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority

- Philadelphia Housing Authority

- American Institute of Architects Philadelphia Chapter

- Community Design Collaborative

- Camden Churches Organized for People

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

- Inner City Organisations Network (ICON)

- Campaign to Take Back Vacant Land

- Women’s Community Revitalization Project (WCRP)

- Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation

- Project HOME

- Pennsylvania Land Trust Association

- Venturi’s Guild House: 50 Years Of Everyday Extraordinary Design (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- PhilaPlace: Guild House (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)