Benjamin Franklin Parkway

By Lynn Miller

Essay

Created in the first decades of the twentieth century, the Benjamin Franklin Parkway connected the heart of Philadelphia’s downtown to its premier park and over time became a district of cultural institutions and a commons for civic celebrations. The broad boulevard and its monumental structures reflected the European-inspired, nationwide City Beautiful Movement embraced by the emerging city planning profession.

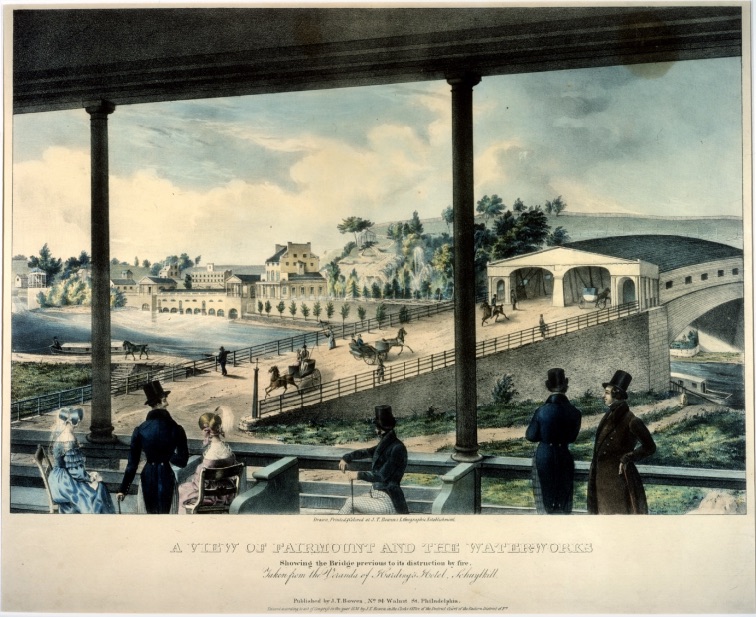

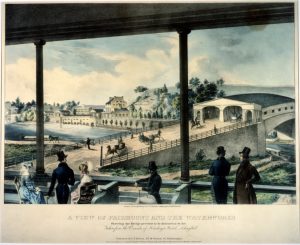

Before the Parkway, Philadelphia’s congested downtown lacked any convenient or ceremonial road to give urban dwellers access to Fairmount Park, its bucolic setting beside the Schuylkill River, and the inspiration of the beautiful classical architecture of the Fairmount Water Works. As the park extended to some three thousand acres along both banks of the Schuylkill shortly after the Civil War, suggestions arose for connecting the park directly to Broad Street. In 1871, an anonymously published pamphlet advocated two “grand avenues” extending from north Broad Street, one leading to the east park entrance and the other to a west entrance. Several years later, the construction of City Hall at Centre (Penn) Square made that the more obvious terminus for a single boulevard leading to Fairmount. Following a preliminary proposal in 1884, City Councils authorized the idea with an ordinance signed into law on April 12, 1892. The planned route was then inscribed on official city maps.

Although immediate execution of the plan faltered, in part due to the financial panic of 1893, it harmonized with trends evident in 1893 at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where the temporary “White City” energized planners to embrace a new City Beautiful Movement. The fair’s design of clustered civic structures bound by a broad thoroughfare demonstrated an alternative to prevailing urban conditions of dark, unhealthy neighborhoods. In contrast, City Beautiful principles would open built-up portions of the city to sunlight and allow greater ease of movement.

In Philadelphia, such visions inspired the 1902 formation of the Philadelphia Parkway Association, an organization made of the city’s most prominent and wealthy residents. They released a new grand plan for a Parkway in March 1903, but debates over location and costs delayed its execution. For the next several years, planners fiddled with the route, some breaking its axis at the Cathedral of SS Peter and Paul on Logan Square and continuing the road at a slightly different angle to the Green Street entrance to the park. A more costly option, ultimately adopted, cut straight from the northwest corner of City Hall across Logan Square to the foot of Fairmount. With the exact route still unresolved, work began with the demolition of a little row house on north Twenty-First Street on February 22, 1907.

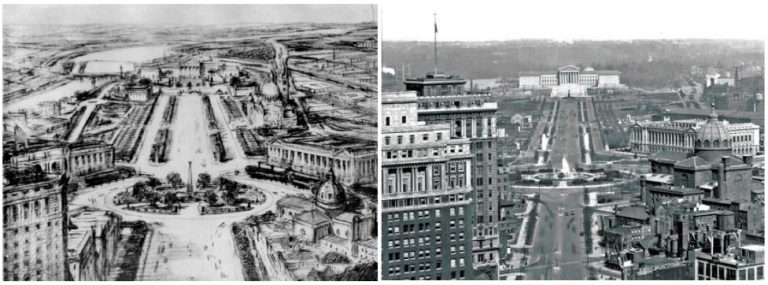

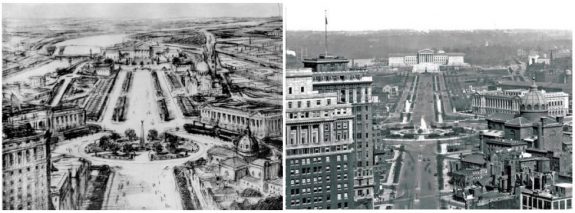

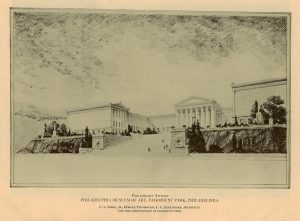

Museum on a Hill

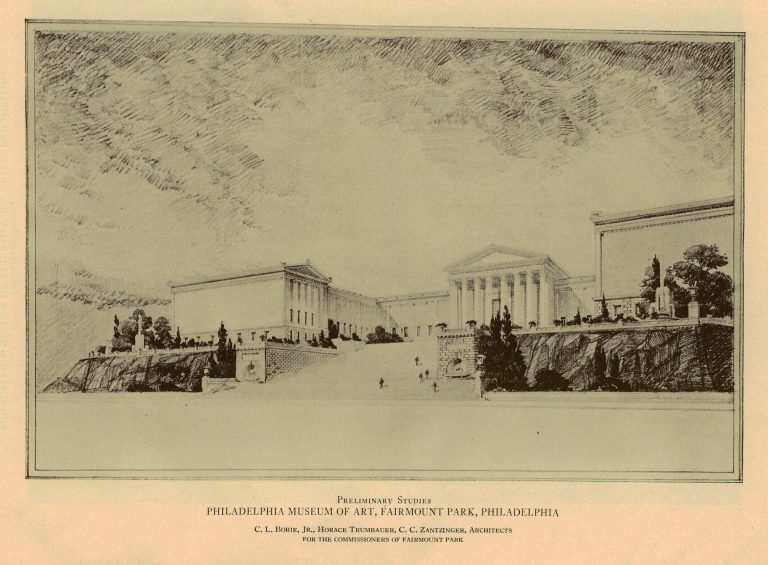

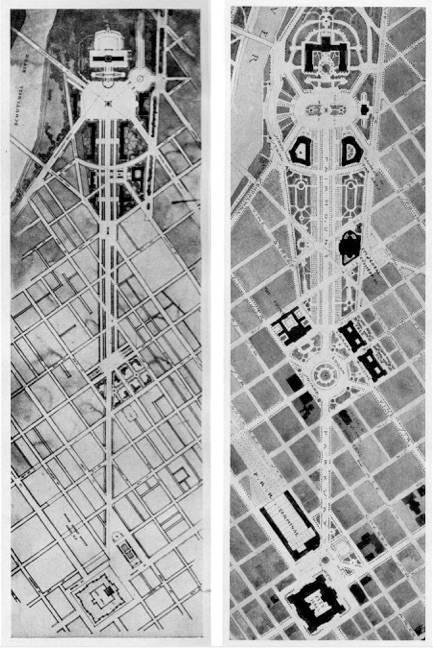

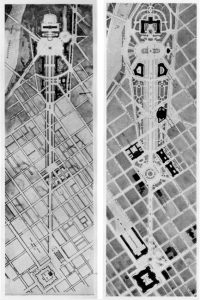

Weeks later, Republican Mayor John E. Reyburn (1845-1914) took office. Within days, he received an invitation to the mansion of one of the city’s most influential Republicans and a leader in the parkway project, the immensely rich streetcar baron and art collector, P.A.B. Widener (1834-1915). For years, Widener had been arguing for a new art museum to replace the distant and crowded facility at Memorial Hall. He informed Reyburn that he would personally pay construction costs for a new museum if the mayor agreed to build it atop Fairmount, where, both men understood, the Water Works’ reservoirs, like the rest of the facility, should soon be closed because of the Schuylkill’s pollution. Accepting Widener’s offer, Reyburn was persuaded that the new boulevard should terminate at the foot of Fairmount. The Fairmount Park Art Association commissioned a new architectural plan to represent for the first time a vision of a Parkway complete with proposed grand new civic buildings. The architects named were the French-born Paul P. Cret (1876-1945), Clarence Zantzinger (1872-1954) and partners, and Horace Trumbauer (1868-1938). By late summer 1907, Cret produced a bird’s-eye view of the plan. It showed a grand rectangular plaza at the foot of Fairmount, a classical art museum at the summit, and a smaller semicircular plaza at the northeast corner of the larger one, where a second avenue would run north parallel to the main Parkway before curving toward the river at Boathouse Row.

The project would be very expensive—some two million dollars more than if the roadway had been shifted slightly away from the foot of Fairmount. Reyburn campaigned for more than a year to win support for it. In 1908, voters approved a loan for the project, and in June 1909, the updated plan returned to official city maps. By the time Reyburn left office at the end of 1911, he was hailed for his leadership of the Parkway project and for making Fairmount the site of the new art museum. High costs and seemingly endless delays postponed completion of the art museum for nearly two decades, however, by which time Widener was long dead and his son had angrily withdrawn his earlier offer to give the family’s vast art collection to Philadelphia.

Adding to the delays were disputes between Mayor Rudolph Blankenburg (1843-1918), a reform Republican who succeeded Reyburn in 1912, and the Republican machine that controlled City Councils. After the Pennsylvania legislature in 1915 gave Pennsylvania cities the right to control construction within two hundred feet of parkland, City Councils voted to annex the Parkway to Fairmount Park, which would give control to the Fairmount Park Commission (FPC), then a bastion of Republicanism. Blankenburg vetoed the legislation, only to have the Councils override him. The commission waited to exercise its authority until 1916, when Republicans restored their rule over City Hall with the election of Mayor Thomas B. Smith (1869-1949). But then things moved quickly. By the time the nation entered World War I in April 1917, the Parkway was nearly complete. The Fairmount Parkway, as it was initially named, was declared fully open on October 25, 1918. More than 1,300 properties had been demolished at a cost of $35 million.

Parkway Plan Gets a Second Look

Seeking to put its own stamp on the Parkway, the Fairmount Park Commission in 1917 hired its own consultant to reexamine the Cret-Zantzinger-Trumbauer plan created nearly a decade earlier. The commission selected French landscape architect Jacques Gréber (1882-1962), the favorite of commission president Edward T. Stotesbury (1849-1938), and early in 1918 approved and published his revised plan. While retaining the basic design of Paul Cret’s 1907 plan, Gréber replaced the monumental plaza that Cret had drawn at the foot of Fairmount with a smaller oval and created a green wedge of largely open space extending down into the city. He also created a traffic circle within Logan Square, which was extended to Twentieth Street. He intended that enlarged space, rather than the plaza at Fairmount, to become the main locus of new public buildings, similar to the Place de la Concorde in Paris.

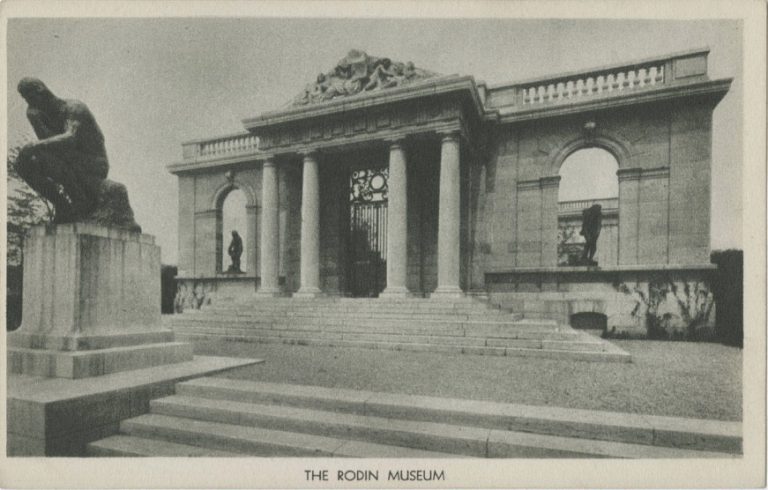

The 1907 plan in which Paul Cret had played such an important role reflected the influence of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he had trained, and the Avenue des Champs-Elysées and other great Parisian boulevards built during the reign of Napoleon III. Gréber built upon those references, particularly in shifting the allusion to the Place de la Concorde from the foot of Fairmount to Logan Square. Between 1927 and 1941, the Free Library by Julian Abele (1881-1950) and Municipal Court building by John T. Windrim (1866-1934) were completed on the square’s north side, an obvious homage to comparable buildings at Concorde. Cret, who had been away from Philadelphia serving in the French army during World War I, was at first unhappy when he heard of the changes made by his countryman. But after he returned at the close of the war, he and Gréber reconciled and went on to collaborate on the Rodin Museum in 1929.

During the decades while the Parkway was on the drawing boards and under construction, a number of buildings were proposed for it but never constructed. Of those eventually built, most were completed between 1918, when the Parkway opened, and December 1941, when the United States entered World War II. These included the Insurance Company of North America (1925) at Sixteenth Street, the Fidelity Mutual Life Insurance Company (1928) at Twenty-Fifth Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, the Philadelphia Council of the Boy Scouts of America (1930) at Twenty-Second and Winter Streets, the School Administration Building (1932) at Twenty-First and Winter, and the Franklin Institute (1934) at Twentieth and the Parkway. The Philadelphia Museum of Art, the vast temple crowning the acropolis of Fairmount, officially opened in 1928, although much of its interior remained unfinished.

Monuments on the Parkway

Outdoor monuments also adorned the Parkway. In 1924, the sprawling Fountain of the Three Rivers (Swann Memorial Fountain) by Alexander S. Calder (1870-1945) was unveiled in the center of Logan Circle, the approximate midpoint of the long view from City Hall to the Museum of Art. In 1928, the Washington Monument designed in 1897 by Rudolf Siemering (1835-1905) was moved from its original home at the Green Street entrance of Fairmount Park to the foot of Fairmount and the terminus of the Parkway.

The Great Depression, then World War II, brought a halt to new projects for the Parkway, which was renamed the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in 1937, a year of festivities marking the sesquicentennial of the U.S. Constitution. Little was added during the second half of the twentieth century apart from a juvenile incarceration facility, the Youth Study Center, at Twentieth Street in 1952. But the 1953 demolition of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Broad Street Station, which had long abutted City Hall at its northwestern corner, made way for the creation of John F. Kennedy Plaza in the 1960s at the Parkway’s southeastern terminus in the block bounded by Fifteenth, Sixteenth, and Arch Streets, and JFK Boulevard. That plaza atop a municipal parking garage opened a broader vista from City Hall to the Art Museum than ever before. It later became known as “Love Park” following the installation of the iconic LOVE sculpture by Robert Indiana (b. 1928). In 1959, the Parkway also gained the Moore Institute of Art (later Moore College of Art) on the south side of Logan Square at Twentieth and Race Streets. Ten years later, between Sixteenth and Seventeenth Streets, the Friends Select School replaced its buildings dating from 1848 with a new school and office building. At the other end of the Parkway, also in the 1960s, to accommodate ever-increasing automotive traffic Gréber’s small oval at the foot of Fairmount was enlarged into the egg-shaped Eakins 0val, named for artist Thomas Eakins (1844-1916).

By the start of the twenty-first century, new Parkway projects came to life with prodding from a 1999 report by the private-sector Central Philadelphia Development Corporation, which laid out proposals for “completing” the Parkway in keeping with the visions of Cret and Gréber. New and renovated park space filled the once-empty corners of Logan Square; new benches, sidewalks and crossings created a better experience for pedestrians; a new Dilworth Park replaced the hard-surface Dilworth Plaza on the west side of City Hall; and new cafés opened at Sixteenth Street and on Eighteenth Street on Logan Square. Paine’s Park for skateboarders arose in the lawn between the roadway and the new Schuylkill Banks park along the riverbank, and Eakins Oval also became a temporary park in the summertime. At Twenty-Fifth Street, the Philadelphia Museum of Art annexed and enlarged the Fidelity Mutual Life building as its Perelman Building with galleries, archives, and office space for the museum. Most importantly, in 2012 the Barnes Foundation opened a new Philadelphia campus on the site of the demolished Youth Study Center on the Parkway’s north side between Twentieth and Twenty-First Streets. With the renovation of the Rodin Museum next door, this at last realized much of the century-old dream of making the Parkway an art-lover’s destination.

In the early decades of the twenty-first century, the Benjamin Franklin Parkway remained one of the greatest achievements of city planning in Philadelphia’s history. The long process that brought it to fruition marked the start of a century in which professionals united with civic leaders and officials to create a bold vision for the heart of the downtown. The result has been both a prime cultural destination for the region and a distinguished civic space for area residents to gather for holidays and other special occasions.

Lynn Miller is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Temple University. He is the author of, among other works, Global Order: Values and Power in International Politics, Crossing the Line (a novel), and the co-author (with James McClelland) of City in a Park: A History of Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park System. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Forums seek a neighbor-friendly vision for Benjamin Franklin Parkway (WHYY, July 30, 2012)

- Setting the scene for transformation of Ben Franklin Parkway (WHYY, February 4, 2013)

- A tree grows in Philly, adding to sculptural luster along Parkway (WHYY, May 30, 2014)

- Franklin Institute, Philadelphia reach compromise on digital sign (WHYY, August 2, 2016)

- Jurassic World has blockbuster opening weekend at Philadelphia's Franklin Institute (WHYY, November 29, 2016)

- Some Philly residents aren't happy about extended NFL visit (WHYY, April 10, 2017)

- Big crowds, hometown hero, loud boos give NFL Draft a distinctly Philly feel (WHYY, April 28, 2017)

- Celebrating a century of Philly's iconic Parkway -- and looking down the road (WHYY, September 8, 2017)

- Philadelphia's Holocaust memorial, nation's oldest, gets a facelift (WHYY, October 22, 2018)

- Philly's African American Museum moving to the Ben Franklin Parkway (WHYY, August 11, 2022)