Iron Production

Essay

Long before western Pennsylvania dominated the American iron and steel industries, southeastern Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey became the epicenter of colonial iron production. In a little over forty years beginning in 1716, Pennsylvania ironmasters erected nearly fifty furnaces and forges for producing iron stock and goods, and by 1840 the region’s national preeminence had been secured—Pennsylvania’s two hundred charcoal furnaces produced 286,000 tons of iron (half the national total), achieving a more than fivefold increase in just thirty years. The foundation for this stupendous ascent began in colonial New Jersey, the birthplace of charcoal-fueled iron production in the Middle-Atlantic region.

Industrial iron production, which originated in North America with the Hammersmith Works (est. 1643) at Saugus, Massachusetts, began in New Jersey in 1674 at the Tinton Falls Ironworks near Shrewsbury, Monmouth County. Ironworks opened in Burlington County, New Jersey, by 1715, and by 1730 Isaac Pearson (c.1685-1749) and his partners had fired the Mount Holly Ironworks—one of the oldest in southern New Jersey. In Pennsylvania, meanwhile, Berks County’s Thomas Rutter (c.1660-1730) ignited Pennsylvania’s first forge, Pool Forge, in 1716 and Colebrookdale Furnace in 1720.

Geographically and geologically, the counties of southern New Jersey were particularly well suited to charcoal-fueled iron production. A chemical reaction between the tannin-rich waters of the Pine Barrens and underlying iron-rich green sands and marls formed iron-rich deposits of limonite, also known as bog iron or bog ore. Bog ore could be harvested from the banks and beds of the region’s swamps and wet meadows with little effort. For fuel, colliers converted tens of thousands of acres of hardwood forests in the west and pines in the sandy east to charcoal. Coastal shell beds could be processed into lime and used as flux. In addition, southern New Jersey’s tidal creeks performed a double service by empowering bellows and massive trip hammers and floating iron from the interior to markets on the Delaware River and beyond. In Pennsylvania the forested Delaware, Schuylkill, and Susquehanna River Valleys provided ironmasters with fuel and waterpower. In contrast to southern New Jersey, where bog iron was easily harvested, Pennsylvania’s ironworkers had to mine natural deposits of magnetite, hematite, and carbonate to secure ore. In the absence of shell beds limestone deposits served as flux for their furnaces.

The earliest colonial ironworkers typically operated simple furnaces known as bloomeries or Catalan forges. In these forges bloomsmen smelted (extracted) workable iron directly from base iron ore or from molten “pig” iron produced by the furnace. While some ironmasters anticipated shipping their iron stock to Britain, most sold to local craftsmen who produced wrought-iron nails, tools, hardware, wheel rims, and horseshoes for domestic markets, or directly to local merchants and consumers as cast-iron hollow ware and stoves.

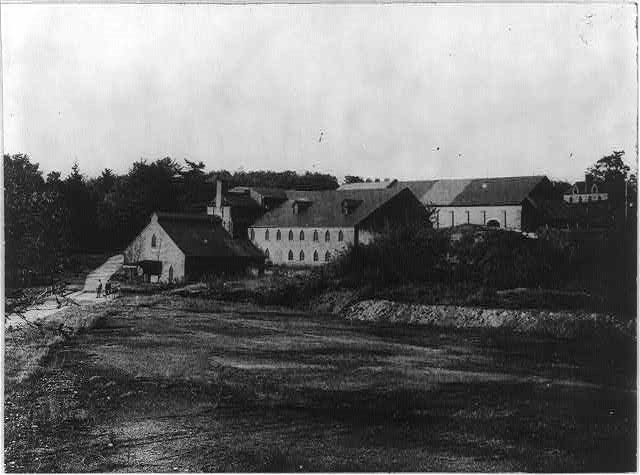

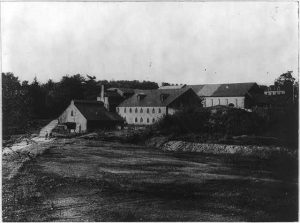

Early ironworks in southern New Jersey and southeastern Pennsylvania operated as nominally self-sufficient iron plantations. The ironmaster, founders, fillers, guttermen and colliers (some slaves, some freemen) lived on the plantation with their families. They shopped in company stores, and their children went to company schools. In addition to the furnaces and the “big house,” plantations frequently featured sawmills and gristmills, fields and orchards, stables and corncribs. Perhaps the best documented plantations were those developed by Charles Read (1715-74) of Burlington City and his partners from Philadelphia and New York between 1765 and 1767. They built New Jersey’s Atsion (1765-c.1846), Batsto (1766-c.1850), Etna (c.1766-73), and Taunton (c.1776-c.1830) ironworks. Well-preserved and well-documented ironworks in southeastern Pennsylvania include Hopewell Furnace (1771-1883) established by ironmaster Mark Bird (1738-1812), Cornwall Furnace (1742-1883) established by Peter Grubb (c.1702-54), and Johanna Furnace (1791-1898).

During the eighteenth century, domestic demand for bar iron, cast iron, and iron products increased while English iron production experienced stresses like Queen Anne’s War (1702-13). In response, mid-Atlantic colonial iron makers invested in a more efficient, indirect method of iron smelting that permitted greater yields than the bloomery forge. By using a blast furnace that operated at a significantly higher temperature, smelters were able to convert iron ore to a stew of molten metal and slag; the liquefied iron could then be drawn off into molds. To produce workable iron like that from a bloomery forge, the molten iron could be further processed in a finery forge and shingled to produce more flexible and ductile bar iron.

The indirect method of smelting was more complicated, required substantially more labor, and initial costs were high, but this indirect smelting process was more fuel-efficient. Using the indirect method, even poor grade ores could be employed to produce high grade iron. To meet the demand of growing markets, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries other technologies that increased efficiencies, lowered costs, and expanded the range of domestic and industrial products available were adopted, including the slitting mill, the rolling mill, and the coal-fired puddling furnace. By 1750 American ironmasters became major suppliers of iron to British manufactures and by 1775 they were the third-largest producers of iron in the world.

Iron production in the hinterland provided Philadelphia with plentiful supplies of coal, coke, and pig iron, which supported craftsmen and manufacturers in the city. By 1810 Philadelphia became home to several dozen iron-dependent manufacturing interests—carriage makers, gun factories, naileries, saw factories, and more—as well as several hundred blacksmiths. By the 1870s nearly two hundred fifty blacksmiths and nine hundred manufacturers of iron goods (and one blast furnace) could be found in the city. Manufacturers produced hardware, hollowware, and stoves; steam engines and boiler plate; locomotives and ships; and iron stock (bar iron and sheet iron). Nineteenth-century iron goods manufacturers in and around Philadelphia included the Schuylkill Ironworks at Conshohocken (est. 1837), a rolling mill that produced sheet and plate iron; the Port Richmond Ironworks of I.P. Morris, Towne & Co. on the Delaware, which produced machinery, steam engines, and boilers (est. 1845); the Baldwin Locomotive Works (c. 1831-1920s); and, the William Cramp & Sons Ship and Engine Building Company shipyard (1830-1927).

Although a few iron plantations persisted into the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, most were gradually supplanted by the 1840s. In southern New Jersey, difficulties became evident by the early nineteenth century when most ironworks, having exhausted local supplies, had to import both fuel and iron ore by barge. At the same time charcoal-fueled iron production could not compete with newer, more efficient furnaces that employed anthracite and coke-fueled hot-blast technology. Furthermore, while charcoal iron was suitable for products such as agricultural implements and nails, railroads and other nineteenth-century industries preferred more durable hot-blast iron produced with anthracite coal and coke. Iron producers in southeastern Pennsylvania fared somewhat better. The advent of new smelting processes and technologies that employed coal or coke as fuel, together with the discovery of high grade mineral ores in the interior, competition from English producers, and cyclical market fluctuations, caused a gradual shift of the center of the iron industry to the north and west. There, ironworks could be established closer to Pennsylvania’s anthracite and bituminous coal deposits and sources of high-grade mineral ore. Those ironworks in southeastern Pennsylvania that managed to remain competitive into the twentieth century did so by producing technically complex specialty products like boiler-plate, mechanical components, ship hulls, and steel.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the last of the charcoal iron forges and furnaces in southeastern Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey were cold and quiet. Even older operations that adopted new technologies and fuels gradually fell to larger, more efficient competitors in the West. By the 1880s the Durham Furnaces (c. 1850–c.1887) and Bristol Forge (c. 1844–before c. 1878) of Bucks County were shuttered, as well as Merion Furnace (c. 1847-1880) and Norristown Furnace (c. 1869-1874) in Montgomery County; Isabella Furnace (c. 1835-1880) and Hibernia Rolling Mill (c. 1835- before c. 1880) in Chester County; and the Old Sable Iron Works in Delaware County (c. 1808-before 1875). Nonetheless, Pennsylvania’s iron producers and manufacturers remained competitive into the twentieth century by adopting new technologies and developing new products. Not until the latter twentieth century did the widespread deindustrialization of the American economy finally crush iron and iron-goods production in Pennsylvania, destabilizing the economy of entire regions, depopulating once thriving cities, and initiating a decades-long search for ways to reclaim the prosperity that the iron industry once provided.

Brian Albright is a graduate of Rutgers University-Camden and Senior Historian at engineering firm AECOM in Burlington, New Jersey. His interests include the industrial, labor, and social history of Philadelphia in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries and the environmental history of the mid-Atlantic region. (Author information current at time of publication).

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- The Pennsylvania Iron Industry: Furnace and Forge of America (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Hopewell Furnace History and Culture (Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site)

- Hopewell Village and the Colonial Iron Industry (National Park Service Regional Review)

- Ore Pile (Batsto Village)

- Iron Beginnings in America (Penn State University)