Norristown, Pennsylvania

By Michael D. Schaffer | County Seat

Essay

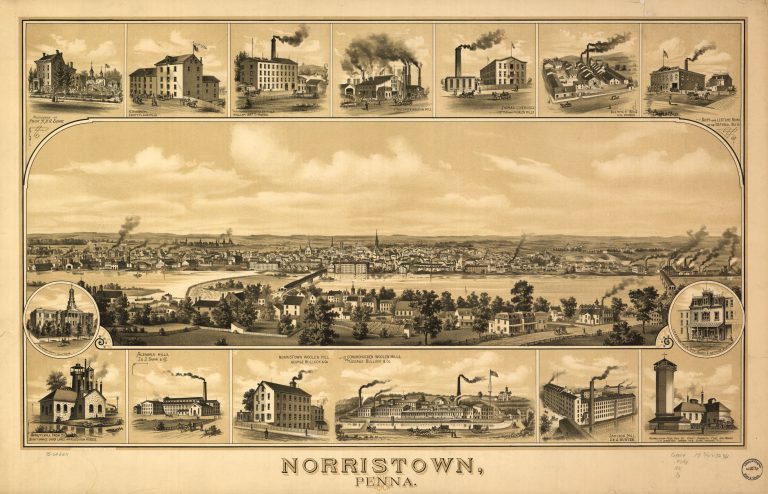

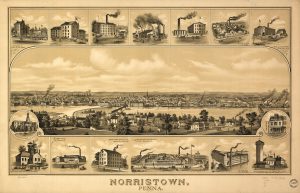

Founded in 1784 as the county seat of Montgomery County, Norristown sits on three hills that slope down to the Schuylkill River fifteen miles northwest of Center City Philadelphia. Its riverfront location and abundant waterpower helped the town prosper throughout the nineteenth century and much of the twentieth. In the second half of the twentieth century, however, social and economic change undercut Norristown’s manufacturing and commercial base, turning it from a flourishing regional hub into the impoverished county seat of one of America’s richest counties.

Pennsylvania proprietor William Penn (1644-1718) bought the land that became Norristown from the native Lenni Lenape. On October 2, 1704, Penn gave his son William Penn Jr. (1681-1729) a 7,482-acre tract that he called the Manor of Williamstadt. Just five days later, the younger Penn sold Williamstadt to merchants Isaac Norris (1671-1735) and Willam Trent (1653-1724) for 850 pounds. Trent sold his share to Norris in January 1712 for 500 pounds. In 1730, the Court of Quarter Sessions for Philadelphia County ordered the name of the tract changed from Manor of Williamstadt to Norriton Township.

The new settlement was well-situated for success. The canoe-navigable Schuylkill, a natural passage from Philadelphia into Pennsylvania’s rich interior, developed into a highway for transporting farm products and coal to the city. Stony Creek and Saw Mill Run, two tributaries of the Schuylkill, offered an abundant source of water power for mills of all sorts. Norriton, which was part of Philadelphia County, grew quickly, increasing from just twenty landholders and tenants in 1734 to 380 by 1749.

Norris, who never lived in the area that bears his name, died in 1736. The tract then passed through several owners, and in 1776 the College and Academy of Philadelphia purchased 543.5 acres of it. The General Assembly, fearful that the Academy had Loyalist leanings, transferred the land in 1779 to a new institution, the University of the State of Pennsylvania. (The academy and the university merged in 1791 to become the University of Pennsylvania.)

As the outlying reaches of Philadelphia County grew steadily in population, residents began to complain to the General Assembly that the courts in the city of Philadelphia were too far away and petitioned for a new county, with a more conveniently located county seat. Some petitioners wanted the new county to be created solely from land within Philadelphia County, while others wanted it carved out of parts of Philadelphia, Chester and Berks Counties, with a county seat at Pottstown. On Sept. 10, 1784, the Assembly created Montgomery County, taking the land exclusively from Philadelphia, and ordered a courthouse and jail built along Stony Run, on four acres that the university gave “as a free gift” for that purpose. The school also agreed to lay out a twenty-eight-acre county seat, to be called the Town of Norris, with sixty-four building lots for sale.

Big Ambitions

The Town of Norris had only twenty houses by 1790, but the residents had big ambitions. In 1812, they asked Gov. Simon Snyder (1759-1819) for permission to incorporate as a borough–the first in Montgomery County. Snyder agreed, and the Town of Norris, expanded to 250 acres, became the Borough of Norristown on March 31, 1812, governed by a burgess and borough council. In 1853, the borough added another two thousand acres, bringing Norristown to its modern area of 3.6 square miles.

Looking for a symbol that would tell the world what Norristown was all about, borough officials commissioned William Kneass (1781-1840), chief engraver of the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia, to come up with an official seal. Kneass depicted a dome-shaped straw beehive under the Latin motto “Fervet opus”–literally, “The work boils.” The design was apt for a town that wore its hard-working heart on its rolled-up sleeve.

For much of its history, the work did, indeed, boil as Norristown bustled with industry and retail trade. Textile mills, sawmills, and grist mills all flourished through the nineteenth and into the twentieth century. The town’s products included textiles, paper, iron, steel, shirts, shoes, beer, cigars, tacks, flour, lumber, plastics, rubber, animal feed, and even bubblegum. Through the first half of the twentieth century, the variety of Norristown’s industry remained a source of civic pride. The borough also became the county’s marketplace. The number of stores in the town increased from forty-four in 1840 to nearly three hundred in 1883, along with twenty-nine hotels, thirteen restaurants and eight liquor stores.

Norristown’s riverfront location provided a means to move the goods it manufactured downstream to Philadelphia. In the early nineteenth century, Norristown and other towns along the Schuylkill got a boost from the construction of a series of canals owned by the Schuylkill Navigation Company. By 1857, more than a million tons of freight moved each year through the canal system, which ran from Port Carbon in Schuylkill County all the way to Philadelphia.

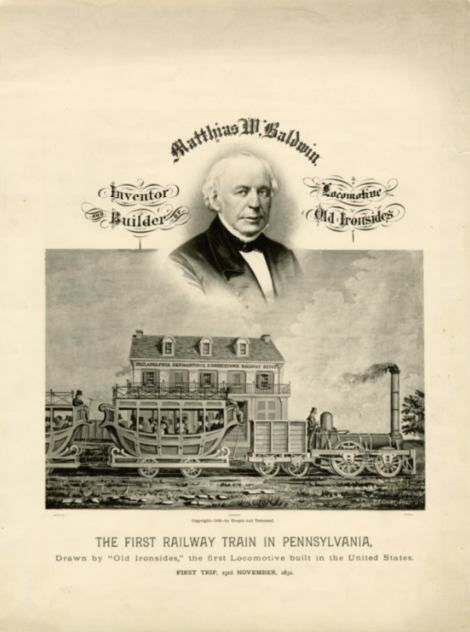

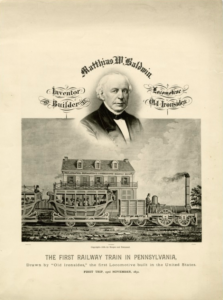

Stagecoaches and, later, railroads also connected Norristown to Philadelphia, enhancing the borough’s status as a marketplace. The first railroad service came to Norristown in 1835 with the arrival of the locomotive Old Ironsides on the Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown Railroad. The borough gained trolley service in the 1880s, and the Philadelphia & Western Railroad, later SEPTA’s Norristown High Speed Line, began service in 1912.

Abundant Jobs

With so many ways to get to Norristown and so many jobs beckoning in the mills and factories, the borough’s population grew steadily. The census of 1820 found Norristown with a population of 827, but by 1850, it was up to 6,026, a sevenfold increase. By 1900, Norristown’s population had climbed to 22,265. It was a heady time for the town, which proudly described itself as “the Biggest Borough in the World.” Population peaked at 38,925 in 1960 before declining to 30,749 in 1990 and rebounding to 34,324 in 2010, largely on the strength of Hispanic immigration.

Wave after wave of immigrants flocked to Norristown in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. They joined the English, Germans, Scots, Welsh, Dutch, and Swedes who had arrived during colonial times. In the mid-nineteenth century, large numbers of Irish settled in Norristown, followed toward the end of the century by Jews and Italians. So many immigrants were arriving, that by 1910 14.4 percent of the borough’s population was foreign-born whites.

Norristown also became a destination for African Americans leaving the South during the Great Migration of the early twentieth century until by 1950 they made up 8.1 percent of the population. Like other newcomers, they looked for work in the factories and mills. Some local enterprises, such as the Alan Wood Steel Co. in nearby Conshohocken, recruited Black workers from other parts of the country. Meanwhile, the number of foreign-born whites in Norristown decreased, reflecting changes in immigration patterns, from 13.6 percent of the population in 1900 to 7.5 percent in 1950.

As the mid-century mark passed, whites began moving out of Norristown for the surrounding suburbs. By 1960, Norristown was 12.4 percent Black, and by 1970 the Black population was up to 21.9 percent. The percentage kept climbing, until by 2010, African Americans made up 35.9 percent of Norristown’s population.

The Modern Era

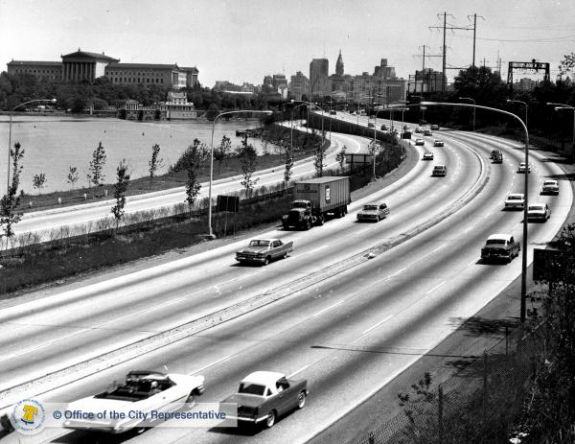

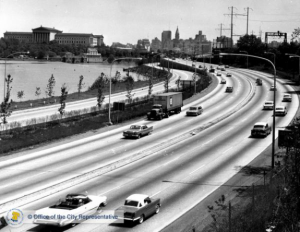

Norristown was never more prosperous and proud than in 1912 when it celebrated its centennial as a borough with a grand parade and pageant, but in the next century the borough’s fortunes declined. Cracks began to develop in the borough’s industrial base over the first few decades of the twentieth century when the textile mills that had been a major part of Norristown’s early economic strength began to move south and cigar makers were unable to keep up with the cost of new technology. In the years after World War II, more businesses relocated. Norristown also lost the transportation advantage that had been so important to its success when the new network of highways–the Pennsylvania Turnpike, the Schuylkill Expressway, and the Blue Route (I-476)–all skirted the borough. The downtown area, which at mid-century boasted two department stores, several theaters, and block after block of shops, suffered as customers shopped instead in the 1960s in suburban malls like King of Prussia and Plymouth Meeting.

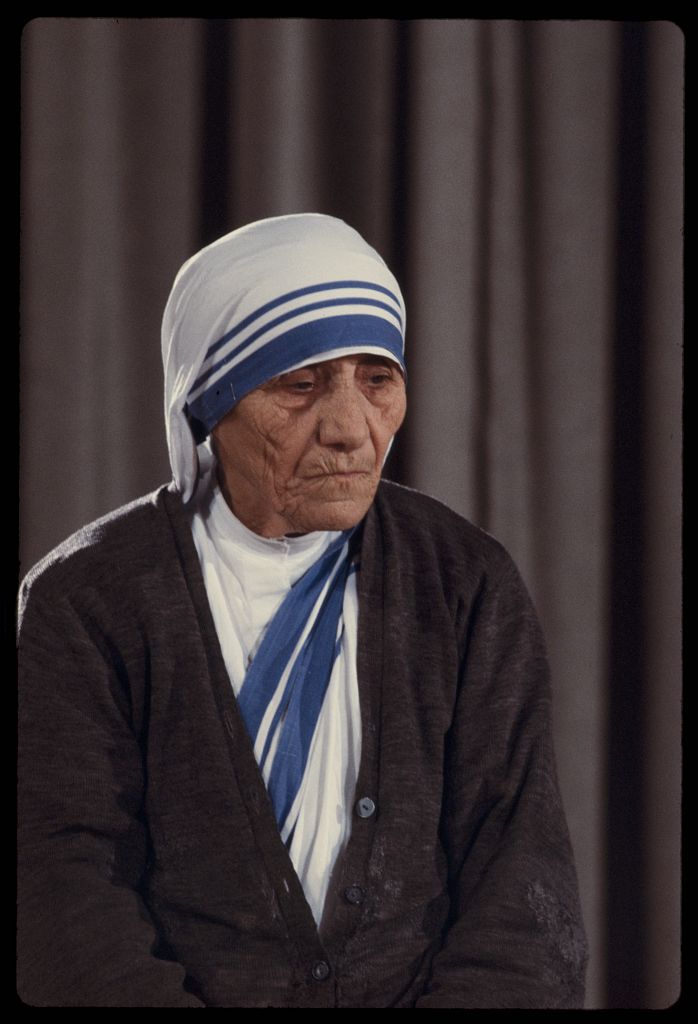

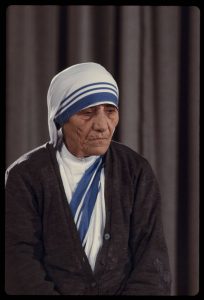

Economic decline brought poverty. By 2010, the poverty rate reached 21.7 percent, compared to 7.1 percent for Montgomery County. Median household income for Norristown was $42,296 in 2014, compared to $79,926 for the county. Norristown had some problems adjusting to the new reality. The town had an uncomfortable moment in the spotlight in 1984 when the Archdiocese of Philadelphia invited the order of nuns founded by Mother Teresa (1910-97) to open a soup kitchen and shelter in the town. Some local officials balked, fearing that the kitchen and shelter would draw the homeless to Norristown, but the Nobel Peace Prize winner —and later, saint—came to town herself, and resistance melted after she met with local officials.

The turn of the twenty-first century marked a new surge of immigration to Norristown as Latinos, mostly Mexicans, arrived in large numbers. Hispanics numbered only 828 in 1990, or 2.7 percent of the population. By 2000, 3,282 persons of Hispanic descent lived in Norristown, or 10.5 percent of the population. By 2010, the number had risen to more than 9,700, or 28.3 percent of the total.

As the town struggled with economic decline, Norristown residents voted in a 1983 referendum to scrap their borough status and become a home-rule municipality, allowing more local control over public affairs. The change took effect in 1986. Norristown switched from government by a burgess (mayor) and twelve-member council to government by a mayor with more power and a seven-member council. The power of the mayor’s office soon became a matter of controversy as spending outpaced revenues, debt piled up, and the town narrowly averted bankruptcy. In 2004, a referendum abolished the office of mayor, leaving government in the hands of the council and an appointed municipal administrator. As if to underscore the hazards of the strong mayor system, a federal probe led to the conviction in 2006 of a former mayor, a former borough manager, a former borough council member, and five local businessmen on charges including bribery and tax evasion.

As Norristown’s fortunes decline, crime went up. In 1972, Norristown police began K-9 patrols in the Main Street area and the town acquired a reputation as place to avoid. Reducing crime became a major point of emphasis for the municipal government. Crime and poverty combined to tarnish Norristown’s reputation. By the second decade of the twenty-first century, Norristown searched desperately for a renaissance. The town’s 2015 municipal report declared that one of Norristown’s “most pressing challenges … is the negative perception that many have about Norristown.”

Government, health care and legal and social services made up the base of Norristown’s economy in the second decade of the twenty-first century. County government was the town’s largest employer. Despite the high poverty rate, Norristown’s unemployment rate in mid-2016 was 5.1 percent – above the national rate of 4.7 percent but below the Pennsylvania average of 5.5 percent.

A promising development for Norristown was the return of theater to downtown. The Centre Theater, which opened in an old Odd Fellows Hall at 208 DeKalb Street in 1996, served as a home for several theatrical troupes and arts groups. The performing company Theatre Horizon moved to Norristown in 2009. The troupe first staged its productions at the Centre Theater but moved in 2012 to the old Verizon building at 401 DeKalb. For nearly twenty years, the Centre Theater also served as home to the Iron Age Theater Company, which was founded in Philadelphia and moved to Norristown in 1995. Beginning in 2014, the troupe staged its productions in various venues in Norristown and Philadelphia. However, efforts to start a movie studio in the old Logan Square shopping center at Johnson Highway and Markley Street foundered after the state legislature reduced film tax credits in 2009 and a California studio that had been interested in the project pulled out.

Despite the failure of the studio project, Norristown’s revitalization efforts continued. Five Saints Distilling, a microdistillery, opened in 2016 in the old Humane Fire Engine Co. No. 1 building at 129 E. Main Street. Norristown officials expected a boost to the town’s economy with a $200 million project to construct a new justice center and renovate the public square on the government campus. An extension of Lafayette Street was expected to improve access to Main Street and the riverfront area and provide Norristown with its own interchange on the nearby Pennsylvania Turnpike. Montgomery County Commissioner Josh Shapiro (b. 1973) described the project as “transformative” – another step in Norristown’s search for a renaissance.

Michael D. Schaffer retired at the end of 2014 after more than thirty years as a writer and editor for the Philadelphia Inquirer. He has a doctorate in American History from Yale University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- $3 million in funding secured for Norristown Area School District (WHYY, August 20, 2011)

- New Norristown police chief to review cooperation with ICE (WHYY, January 7, 2014)

- Mexican immigrants find a home at Norristown church (WHYY, February 8, 2015)

- At Norristown theater, 'In the Blood' explores world of the homeless (WHYY, May 5, 2015)

- Boutique distillery banking on history to lure people to Norristown (WHYY, August 4, 2016)

- 'We knew she's a saint': Mother Teresa's missionary sisters in Norristown carry on her work (WHYY, September 2, 2016)