Smoking and Smoking Regulations

Essay

The origins of smoking tobacco in the Philadelphia region can be traced to the era before European colonization and evolved from pipes and cigars to the commercialization of cigarettes beginning in the late nineteenth century. Philadelphia-area farmers grew tobacco, local manufacturers produced cigars and cigarettes, and the N.W. Ayer advertising agency helped Camel cigarettes become one of the nation’s leading brands. As early as the 1790s, however, Philadelphia physicians began to warn of the health dangers of smoking, and the watershed 1964 U.S. surgeon general’s report on smoking and health ushered in a new era of smoking regulations at the federal level, in Philadelphia, and in the states of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware.

Tobacco was an important plant for the Native Americans of the region, the Lenni Lenape, who lived in small autonomous communities in modern-day Delaware, New Jersey, southeastern New York, and southeastern Pennsylvania. The Lenni Lenape regularly grew and harvested tobacco for consumption. As Europeans arrived in the Delaware region, they observed the Lenni Lenape’s reverence for tobacco, which they smoked in pipes. Tobacco smoking was practiced in a variety of settings, including religious ceremonies, social interactions, and councils, as well as for leisure and as a medical regimen to cure illness.

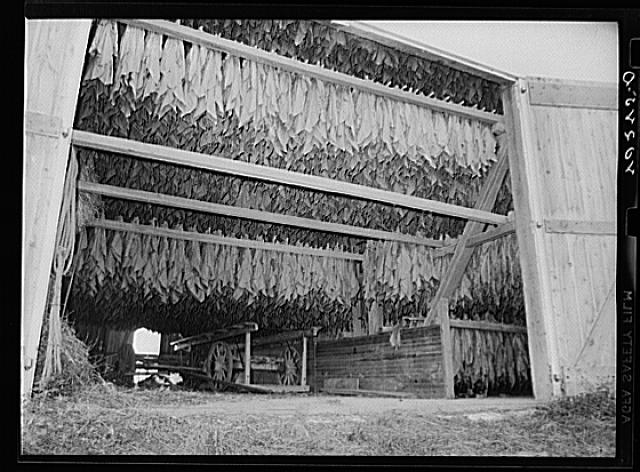

European settlers quickly adopted the practice of smoking dried tobacco in pipes. After lighting the tobacco, the smoker breathed the smoke through the mouth, drawing nicotine and other chemicals into the body, then exhaled out the mouth and nose. Nicotine in the tobacco produced physical and habit-forming effects. The high consumption of tobacco prompted William Penn (1644-1718) to call upon Pennsylvania farmers to pursue large-scale tobacco production. Although large-scale tobacco farming did not come to fruition in Pennsylvania, farmers grew tobacco on a smaller scale, especially among the Amish, in places such as Chester and Lancaster Counties. Small-scale tobacco farming continued into the twenty-first century.

Pipe Smoking

At gatherings and in public spaces in colonial Philadelphia, both women and men partook in pipe smoking, which became widely accepted as a dignified social practice. Pipe tobacco came in a variety of flavors and blends that suited many smokers. Pipes used in Philadelphia and elsewhere were often made of clay, but wealthy smokers used porcelain and silver pipes. Pipe smoking was popular during the colonial period locally, across the British North American colonies, and in England.

By the late eighteenth century, after the American Revolution, cigars gained popularity in the United States and helped further distinguish the newly independent Americans from the British, who favored pipes. Handmade cigars were more convenient, less expensive, and contained more tobacco than pipes. They also lasted longer than pipes and a single cigar could be smoked easily on multiple occasions. During the outbreak of yellow fever in Philadelphia in 1793, cigar smoke was used to treat the disease. The Lenni Lenape used tobacco in the treatment of illness, and early European colonists and doctors also believed it to be effective. When treating a milder yellow fever outbreak in 1762, Philadelphia physician John Redman (1722-1808) kept tobacco in his mouth while visiting with sick patients to help prevent the spread of the disease. Following this precedent, concerned citizens of Philadelphia smoked cigars, hung tobacco in their houses, burned it in their homes, wore it as a clothing accessory, and kept it near their beds to remain healthy during the yellow fever outbreak of the late 1700s.

Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush (1746-1813), a signer of the Declaration of Independence, called attention to tobacco’s negative effects on the stomach, nervous system, and mouth in his essay “Observations upon the influence of the Habitual use of Tobacco upon Health, Morals, and Property” (1798). Although Rush’s claim that tobacco was harmful was later proven true, at the time of publication his assertions were not widely accepted. In the early nineteenth century, additional resistance to tobacco emerged on moral grounds as Quakers in Delaware and Pennsylvania called for boycotts of produce derived from slave labor. Anti-slavery advocates Lucretia Coffin Mott (1793-1880) and James Mott Jr. (1788-1868) of Philadelphia were among the participants in these boycotts. The movement culminated in 1838 when free-produce backers met in Philadelphia and coalesced as the American Free Produce Association.

Meanwhile, the cigar industry grew strong in Pennsylvania in the nineteenth century. In Lancaster County, the town of Conestoga grew famous for producing a low-cost cigar called a “stogie,” the name derived from the town that then became a common nickname for cigars. Numerous cigar factories operated in Philadelphia, the region south of Harrisburg, and the Lehigh Valley. Philadelphia had 490 small cigar factories in Philadelphia by 1882. In the 1910s, larger cigar factories owned by the American Cigar Company, the Bayuk Brothers, the Bobrow Brothers, and Jeitles and Blumenthal employed hundreds, including migrants from Cuba and Puerto Rico. Trenton and Camden, New Jersey, also became sites of cigar production.

Mass Production of Cigarettes

By the late nineteenth century, technological improvements also initiated the mass production of cigarettes, which could be smoked in a similar manner as cigars but were much smaller, less expensive, and milder in taste. Rameses cigarettes, a nationally known cigarette made with Turkish tobacco, began production in 1895 by the Stephano Brothers in Philadelphia. Women and men both smoked, and the Strand Cigarette Company of Philadelphia produced a variety of cigarettes with colored paper on the tip designed to appeal to women. By 1917 approximately ten thousand people worked in the nearly twelve hundred factories manufacturing tobacco products in Philadelphia, and many of these factories produced cigarettes. Improvements in matches made it much easier to light up. A patent lawyer from Philadelphia, Joshua Pusey (1842-1906), redesigned matches by fashioning them out of cardboard instead of wood. A striker included with Pusey’s matches allowed users to easily ignite them on the go.

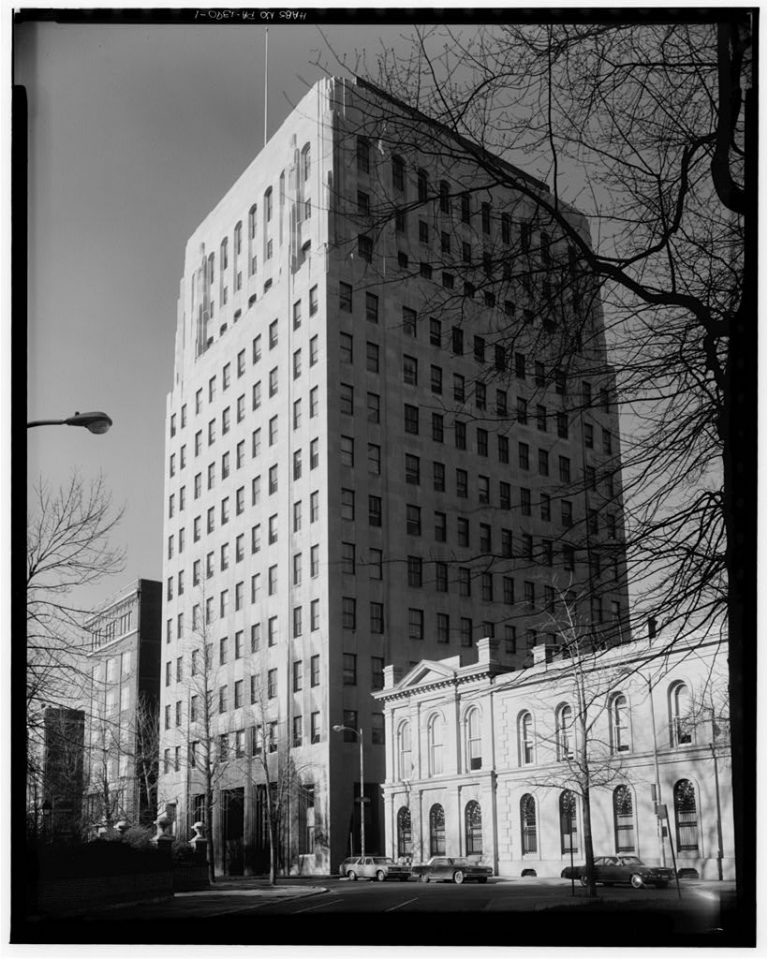

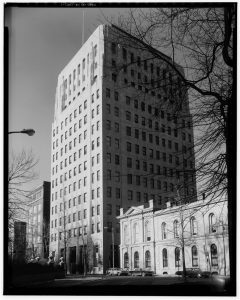

Cigarette smoking grew in popularity during World War I, elevating the significance of the cigarette in American culture. Facing gruesome wartime violence and the constant possibility of death, many soldiers found comfort in smoking cigarettes. Through marketing efforts, smoking was tied to patriotism and Americans showed support for the troops by donating cigarettes. Back at home, cigarettes were consumed in homes, in cars, restaurants, bars, trolley cars, as well as in many other private and public spaces in the Philadelphia region. By the early twentieth century, groups such as the Chicago-based Anti-Cigarette League identified cigarettes as an “evil” influence on health and morality. The group found an ally in Philadelphia department store magnate John Wanamaker (1838-1922), who sympathized with the cause but also disliked smoking by his employees largely because it was an inefficient use of time. He denied employment to cigarette smokers and fired people who lied about their smoking habit. Wanamaker also prohibited advertisements in his stores that depicted smoking. Meanwhile, advertising firms such as N.W. Ayer of Philadelphia (founded 1869) contributed to the popularity of cigarettes. Ayer managed the R.J. Reynolds’ Camel Cigarettes account beginning in 1913 and helped elevate Camel Cigarettes into one of the top three cigarette brands until losing the account in 1930. N.W. Ayer also did tobacco advertising for the Phillip Morris Companies. In the 1930s and 1940s, cigarette ads featured athletes and actors to solidify the product’s cultural significance. Ads also featured cigarette brand recommendations by doctors, which spread the false notion that cigarette smoking was safe.

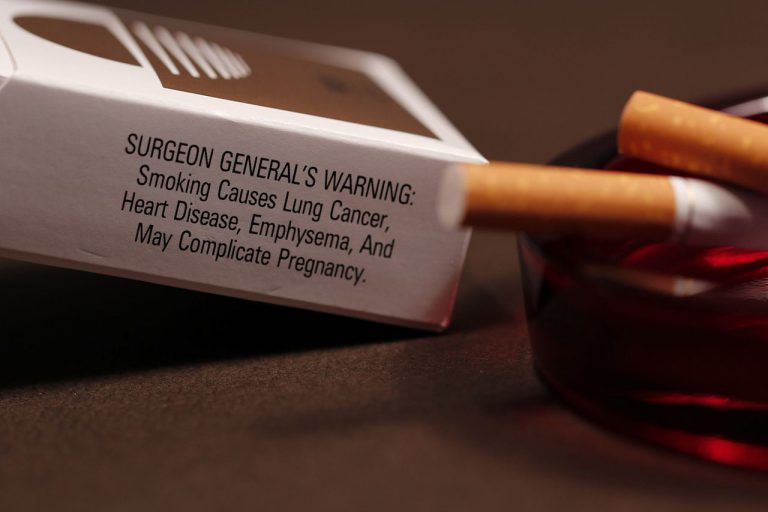

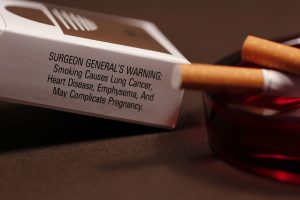

A benchmark event in 1964 forever changed the history of cigarettes in the United States and ushered in a new era of regulation at the local, state, and federal levels. U.S. Surgeon General Luther L. Terry (1911-85), in a report titled Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the United States, identified cigarette smoking as habit-forming and linked smoking to lung cancer and heart disease. (The next year, Terry joined the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania and became a member of Philadelphia’s medical community.) The year the report was issued, cigarette consumption in the United States dropped between 15 and 20 percent. Cigarette sales rebounded the next year, but the report validated the harmful effects of smoking and began to change the American public’s perceptions of cigarettes. Subsequent research tied smoking to more health problems such as other cancers, asthma, stroke, and health risks for nonsmokers from secondhand smoke exposure. New federal legislation mandated health warnings on cigarette packs (1965), banned advertising cigarettes on radio and TV (1971), and required states to pass laws setting age 18 as the minimum age for purchasing cigarettes (1992).

State responses included Pennsylvania’s relatively weak Clean Indoor Air Act of 1988. Under the influence of tobacco companies, the law prevented localities from passing anti-smoking laws stronger than those of the state, but it exempted Philadelphia, which gave the city the power to enact local tobacco control measures. The work of Philadelphia’s medical community helped show the harmful effects of tobacco smoke exposure and the need for stronger laws to ban smoking in public places. For example, University of Pennsylvania researcher Dr. Frank T. Leone (b. 1962), whose research focused on the impact of tobacco on the respiratory system and treatments for tobacco dependence, served on Pennsylvania’s Tobacco Use Prevention and Cessation Advisory Committee beginning in 2001. In 2000, Philadelphia Health Commissioner Dr. Walter Tsou helped secure a local ordinance authorizing the Philadelphia Health Department to investigate the level of secondhand smoke exposure in restaurants with smoking and nonsmoking sections. The study concluded that despite the designated sections, patrons in nonsmoking areas were still exposed to secondhand smoke.

Indoor Protection Against Smoke

After much deliberation, in 2006 the Philadelphia City Council passed the Clean Indoor Air Worker Protection Law, sponsored by Councilman and future mayor Michael Nutter (b. 1957) with support from groups such as Smokefree Pennsylvania and the American Heart Association. Although opponents such as the Philadelphia Hospitality and Business Alliance and the Licensed Beverage Association expressed concerns that a law banning smoking could have a negative economic impact on sales at bars and restaurants, smoke-free laws had strong public support. The resulting ordinance prohibited smoking in a host of public spaces including offices, restaurants, most bars, theaters, and sporting venues. (In adherence with state law, smoking remained permitted on the gaming floors of casinos in Philadelphia.) A 2013 study funded by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that the smoke-free regulations in Philadelphia and Pennsylvania did not cause a negative economic impact for bars and restaurants.

Pennsylvania lagged behind Delaware and New Jersey in enacting smoke-free legislation. Delaware prohibited smoking in all indoor workplaces, including gaming facilities, non-hospitality work spaces, restaurants, and bars when it passed the 2002 Clean Indoor Air Act. The act also made it legal for local governments to enact stricter smoking bans than those passed at the state level. New Jersey banned smoking in residence halls at all universities and colleges in 2005. The following year, the state enacted the Smoke-Free Air Act of 2006, which made it illegal to smoke in enclosed public spaces, including bars and restaurants. Widener University in Chester, Pennsylvania, became the first Philadelphia-area four-year college to ban smoking in indoor and outdoor spaces across campus in 2010.

Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware all benefited from a major settlement of federal lawsuits filed by states against tobacco companies over the health effects of cigarette smoking. After tobacco companies reached a settlement to pay $40 billion to four states, the Master Settlement Agreement of 1998 ordered the companies also to pay $206 billion to the other forty-six states over a twenty-five-year period as compensation for the Medicaid costs accrued due to illnesses related to smoking. The settlement also created a national endowment dedicated to lower smoking rates and new regulations for cigarette advertising. Pennsylvania received $11 billion, New Jersey $7.5 billion, and Delaware $774.5 million.

Changes to tobacco control in Pennsylvania began to take shape in 2007 when State Senator Stewart J. Greenleaf (b. 1939), representing the Twelfth Senate District of Bucks and Montgomery Counties, proposed a new Clean Indoor Air Act. The resulting law in 2008 banned smoking in most indoor public spaces in Pennsylvania but permitted it in designated areas of casinos, bars, and enclosed bar areas of restaurants. Bars accruing less than 20 percent of revenue from food sales also could allow indoor smoking, an exemption criticized as confusing by the American Lung Association of the Mid-Atlantic. The law allowed local governments to pass smoking regulations in outdoor public spaces such as parks, and it acknowledged Philadelphia’s 2006 smoke-free law, which remained legal. Like the earlier Clean Air Act of 1988, however, it prevented local governments other than Philadelphia from passing stronger tobacco control laws than those of the state.

The longstanding practice of smoking tobacco in the Philadelphia region changed significantly after the federal government shed light on the health risks in 1964. Still, between 2005 and 2009, an average of 70,411 annual deaths in Pennsylvania, 4,082 annual deaths in Delaware, and 39,091 annual deaths in New Jersey were attributed to smoking. From 2014 to 2015, the Centers for Disease Control estimated that the percentage of adults age 18 or older who identified as tobacco smokers was 18.1 percent of adults in Pennsylvania, 17.4 percent of adults in Delaware, and 13.5 percent of adults in New Jersey. While smoking rates declined after 1964, the adverse effects of tobacco smoke exposure continued to take its toll, making the practice of smoking one of the largest public health issues in American history.

Timothy Olewniczak is an independent researcher who earned a Master’s Degree in History from the University at Buffalo. He is the author of an article about alcohol prohibition in Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Starting the conversation on Philly's tobacco policy (WHYY, September 26, 2011)

- Tobacco companies drop challenge against Delaware (WHYY, November 16, 2011)

- Tobacco expert makes a case for banning the butts at Penn (WHYY, October 2, 2013)

- N.J. last in nation on funding tobacco-prevention efforts (WHYY, December 11, 2013)

- CVS to quit tobacco sales (WHYY, February 5, 2014)

- Pa. might raise age limit for buying tobacco (WHYY, October 19, 2015)

- At Pa. rally, tobacco opponents tout cigarette tax benefits (WHYY, July 8, 2016)

- Philadelphia's tougher regulation of tobacco sales expected to start Jan. 1 (WHYY, October 21, 2016)

- Trenton raises age to buy tobacco products to 21 (WHYY, February 20, 2017)

- Smoking is often the hardest 'vice' to quit (WHYY, June 8, 2017)

- Penn State study: Vapers report less dependence, addiction than cigarette smokers (WHYY, June 28, 2017)

Links

- Airways Biology Initiative (University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine)

- Broken Promises to Our Children: A State-by-State Look at the 1998 State Tobacco Settlement 18 Years Later (Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids)

- CASAA: Bill Godshall’s Tobacco Harm Reduction Update. (Consumer Advocates for Smoke-Free Alternatives Association)

- State Tobacco Activities Tracking and Evaluations (STATE) System (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- John Wanamaker Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Joshua Pusey Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Lancaster County Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Tobacco Settlement Fund (PDF, Pennsylvania House Democratic Caucus)