Tobacco

By Diane Wenger

Essay

Growing, trading in, and manufacturing tobacco were important components of the economy and society of the Delaware Valley for centuries. Early residents raised tobacco for personal use and as a trade commodity, but in most of the region it fell out of favor by the late eighteenth century. The exception was Southeast Pennsylvania, where tobacco remained an important crop well into the twenty-first century. From the 1750s through the 1950s, the region was a center of snuff, chewing tobacco, and cigar production. Health concerns led to a decline in tobacco use after the 1960s, and international mergers and acquisitions, along with an economic recession, resulted in the closing of many regional tobacco manufacturing facilities.

The first tobacco farmers in the Delaware Valley were Native Americans who grew it for chewing, smoking, and religious ceremonies. New Sweden settlers cultivated tobacco, employed it as commodity money, and exported it to Europe. The English who followed also raised tobacco, using it to pay taxes and land rents to William Penn, and exporting it; in 1706, about eight hundred hogsheads of tobacco were shipped out of Philadelphia. In Delaware, tobacco (grown in the lower part of the colony) was an important export crop in the early 1700s but went out of favor by the 1770s. Early New Jersey farmers grew tobacco for personal consumption, but it never became a commercial crop there.

Tobacco grown in the Philadelphia region in the eighteenth century proved inferior to Chesapeake varieties and commanded a lower price. As a result, most local farmers shifted to wheat production, although some still grew tobacco for personal use. After 1815, the market for wheat contracted, and in the 1830s southeastern Pennsylvania farmers began raising seed leaf tobacco (used as cigar filler) commercially. Many tobacco farmers were Lancaster County Amish and Mennonites, whose large families were able to produce the labor-intensive crop economically. By 1859 Lancaster County was producing 65 percent of the state’s tobacco crop.

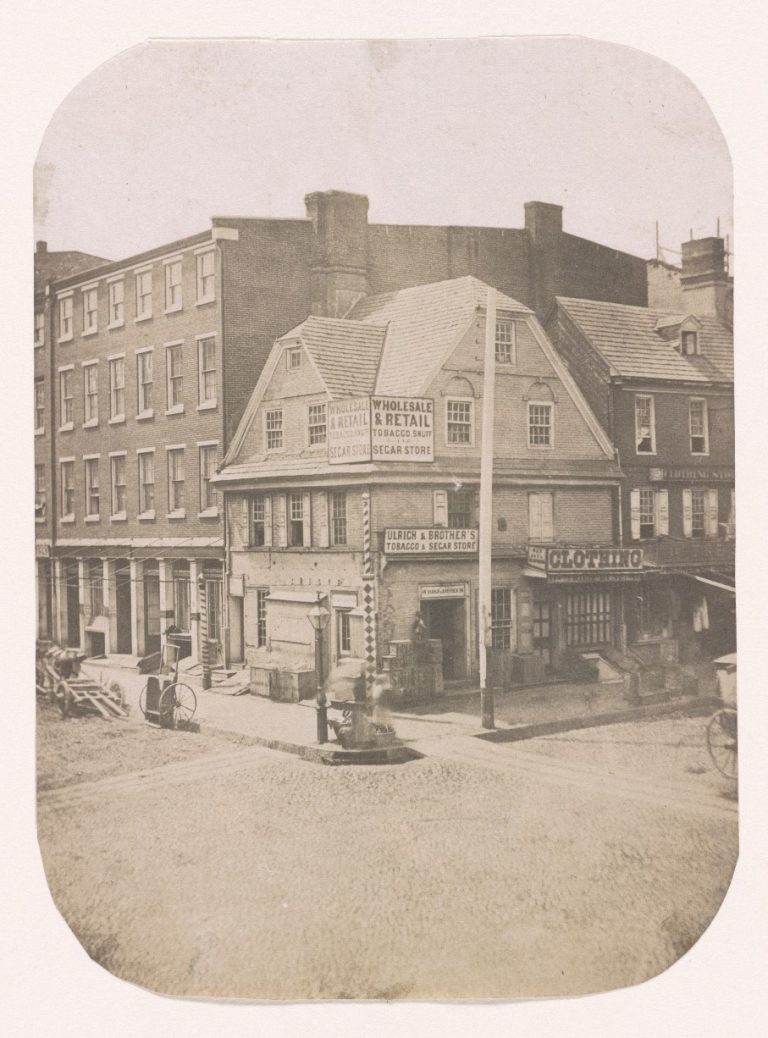

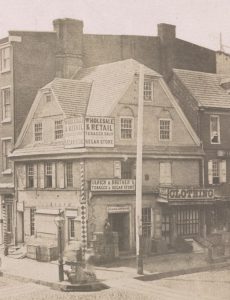

Trading in tobacco was profitable because men and women of all ranks in early America used and became addicted to it. Relatively affordable for the working class, tobacco was prized for its stimulant qualities, and smokeless forms could be used at work without fear of fire. Rural storekeepers, tavernkeepers, and urban tobacconists sold the product in many forms. Depending on how the tobacconist processed the leaves, tobacco was chewed, smoked in a pipe, or taken nasally as finely ground snuff.

Healing Qualities Promoted

For the upper class, expensive snuff boxes of exotic wood and metal were status symbols. Snuff also was believed to have healing qualities. In 1756, one Philadelphia tobacconist advertised it as “good for the Headach(e) and a great Preserver of the Eyes.” Snuff was quite popular with elite Quaker women, including diarist Elizabeth Drinker (1735-1807), who in 1803 noted she had used snuff for over fifty years. While snuff and chewing tobacco were widespread, imported cigars were the most expensive form of tobacco in the eighteenth century, and smoking a “segar” was a sign of conspicuous consumption.

In the revolutionary era, tobacco imported from the South became an important trade item for Philadelphia. In 1775 Virginia growers turned to Philadelphia merchants after expelling British firms, and tobacco became Philadelphia’s principal export; one resident described it in 1779 as “our Staple Commodity.” From 1785 to 1787 Philadelphia merchant Robert Morris (1734-1806) enjoyed a monopoly on selling American tobacco to France as the result of his exclusive agreement with the French Farmers-General.

Coastal trade in tobacco continued to be a valuable part of city commerce through the nineteenth century. The partnership of Tunis & Annesely, for example, operated sloops that sailed between Philadelphia and ports as far south as Virginia. Their cargo included tobacco that they wholesaled to local and regional tobacconists, including Lancaster snuff maker Christopher Demuth (1738-1818) who, between 1803 and 1813, purchased an average of seventeen thousand pounds of tobacco annually from the firm. Country storekeepers such as Samuel Rex (1766-1835) of Schaefferstown, Lebanon County, also relied on city tobacconists for chewing and smoking tobacco and snuff to resell to rural customers.

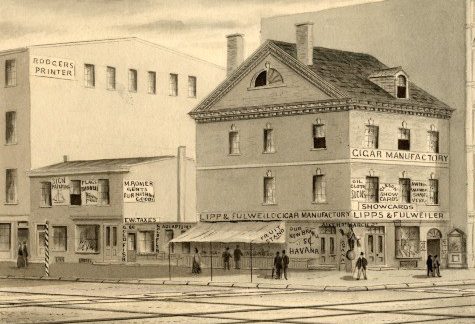

Tobacco products helped fuel the regional economy from the eighteenth through the twentieth century. By 1794, Philadelphia’s twenty-seven snuff and tobacco factories employed over four hundred workers. A 1796 tax assessment showed that New Jersey had one snuff mill and Delaware had two, including the Garret Mill, established in 1782 in New Castle County on the Brandywine Creek, which manufactured snuff for over a century in a modified grist mill. Wilmington, Delaware, was also the site of a tobacco manufactory, according to a 1799 traveler’s account. The 1810 report on manufactures by Tench Coxe (1755-1824) documented Philadelphia (city and county) as leading the state in producing snuff and cigars; the latter included more expensive “Spanish” type and a “common” variety. As snuff faded in popularity, cigars became the preference of tobacco consumers in the mid-nineteenth century. A federal government report by E. H. Mathewson in 1912 showed Pennsylvania leading the nation in cigar manufacturing and listed Philadelphia (along with Pittsburgh and Lancaster) as a center of production. Many small factories also flourished in rural villages throughout southeastern Pennsylvania.

Cigar-Maker Immigrants

The lively trade in tobacco (and sugar) between Philadelphia and the Caribbean in the nineteenth century inspired Puerto Rican and Cuban cigar makers to migrate and find work in the city’s tobacco industry, which included, according to one estimate, some nine hundred factories by the turn of the twentieth century. Southwark, an area of concentrated Spanish settlement, became home to many of these facilities, including Bayuk Brothers Tobacco Company, founded in 1896. By the early twentieth century, Bayuk was Philadelphia’s largest cigar producer, manufacturing Garcia y Vega and the popular “Philadelphia Hand Made Perfectos,” which soon became known simply as “Phillies.”

The Northern Liberties hosted many factories, including Theobold & Oppenheimer, which began production in 1860 and moved to a new plant at 1147 N. Fourth Street in 1900. Most of T&O’s seven hundred employees were women. When Philadelphia’s male cigar makers went on strike in 1888, factory owners installed machines operated by female workers, who could be paid less than men. By 1915 city factories employed four thousand three hundred women—more than twice the number of males.

Cigars also were a major industry in Trenton from the late nineteenth to mid-twentieth century. The elegant factory erected by the firm of Henry Clay and Bock & Company in 1932 at a cost of five hundred thousand dollars surrounded a central courtyard and resembled a tropical hotel. (The Henry Clay took its name from its line of cigars named after the famous Kentucky senator.) In their heyday, Trenton’s cigar factories employed as many as two thousand workers, mostly female immigrants from Hungary, Poland, and Italy.

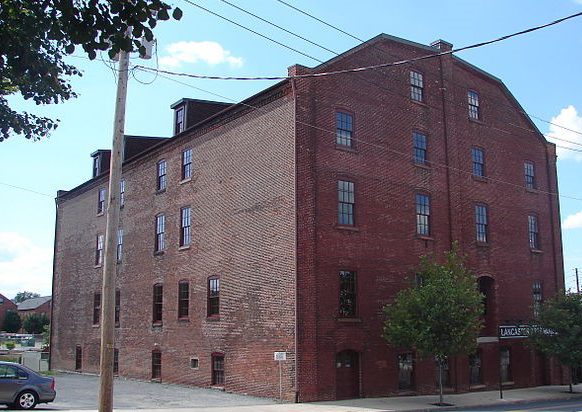

Much of the raw tobacco that these cigar manufacturers used came from Lancaster County, where tobacco reigned as the leading cash crop from 1840 all the way to 2000, making its warehousing and distribution important components of the Lancaster (city) economy. The industry had close ties with Philadelphia cigar makers, including Bayuk Brothers and Otto Eisenlohr & Brothers, both of whom, in the early 1900s, built large tobacco warehouses on North Water Street in Lancaster. (Bayuk eventually took over Eisenlohr.)

Mergers Undermine Local Production

Because of the declining popularity of cigars, the economic downturn, and a series of international acquisitions and mergers, the mid-1900s marked the end of major cigar production in the region. Bayuk closed its Philadelphia plant in 1976. In 1982 Culbro Corportion acquired Bayuk’s Garcia y Vega line, and Bayuk sold its Phillies brands to Phillies Cigar Co., a subsidiary of Havatampa, which later became Altadis, U.S.A. After a period of decline, many former tobacco buildings underwent adaptive reuse, and the former industrial sites became desirable for residences and new business. Henry Clay in Trenton and Theobold & Oppenheimer in Philadelphia were converted into high-end apartments. A number of Lancaster’s former tobacco warehouses were repurposed for hotels, apartments, and restaurants, and many qualified for the National Register of Historic Places.

Another factor that affected tobacco use was the U.S. surgeon general’s 1965 “Report on Smoking and Health,” which led to warning labels on products and a ban on certain forms of advertising. Still, tobacco did not go away, and cigar-smoking enjoyed renewed popularity during the 1990s. By the early twenty-first century, boutique tobacco shops and cigar bars were a fixture in urban areas, and small companies, such as John Hays Cigars of Intercourse, Lancaster County, still made chewing tobacco and cigars using locally grown tobacco. Lancaster Leaf Company, housed in the former Bayuk-Eisenlohr complex, and Domestic Tobacco were the only two tobacco processing operations left in Lancaster, but both carried on sizable businesses. For Lancaster County farmers, tobacco remained a major, lucrative crop. In 2015, the U.S. Department of Agriculture ranked Pennsylvania sixth nationally in the value of tobacco.

Tobacco played a crucial role in the regional economy for more than three hundred years. Until its adverse physical effects were recognized, growing, exporting, manufacturing, and using tobacco products provided employment and consumer satisfaction to many. Even into the first decades of the twenty-first century, despite negative associations, tobacco remained a major agricultural crop for Pennsylvania. Tobacco production and consumption, although less robust than in the past, continued. In places where tobacco companies failed, many sites associated with the industry were recognized for their historic significance and reinvigorated through adaptive reuse.

Diane Wenger is Associate Professor of History and co-chair of the Division of Global Cultures: History, Languages & Philosophy at Wilkes University. She is the author of A Country Storekeeper in Pennsylvania: Creating Economic Networks in Early America, 1790-1807 (Penn State Press, 2008). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Cigar Making in Philadelphia (Temple University Libraries)

- Tobacco In Amish Country (Cigar Aficionado, March/April 1997)

- Lancaster Leaf Tobacco Company

- Lancaster County leads Pennsylvania's tobacco business (Central Penn Business Journal, September 25, 2015)

- Agriculture and Rural Life (ExplorePAHistory.com)