Dancing Assembly

Essay

Established in the winter of 1748-49, the Dancing Assembly of Philadelphia— also known as “The Assembly” or “The Assemblies”— originated as an occasion for elite men and women to gather for social dancing in carefully matched pairs. Modeled after the English “assembly,” a type of formal social gathering most famously held in Bath and London, Philadelphia’s colonial version persisted beyond the American Revolution. Remaining an annual tradition in the twenty-first century, the Assembly became one of Philadelphia’s longest-lasting cultural institutions and the oldest continuously operating subscription dance in the United States.

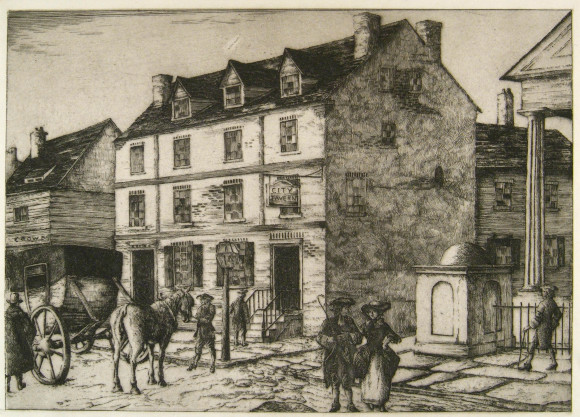

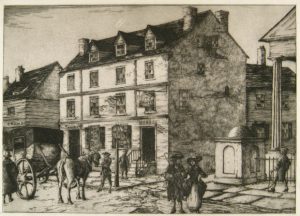

Like the English assemblies it mimicked, Philadelphia’s eighteenth-century assemblies included both formal dances like the minuet and more boisterous “country dances.” Early assemblies also provided entertainment for those inclined not to dance, in the form of card games, and served light fare and drinks, including alcoholic punch. In the first season, the Assemblies were held at Hamilton’s Store or Warehouse on the wharf at Water Street. This location was symbolically fitting and convenient, near the area between Pine and Market Streets where Philadelphia’s leading citizens then lived. It was also near the Delaware River, Philadelphia’s connection to the Atlantic World and the epicenter of the port city’s enviable commercial success.

From the beginning, to attend one either had to be a subscriber (a person invited to be a member who paid a fee for the privilege of attending) or sponsored by a subscriber. The first year each of the fifty-nine subscribers paid a mere forty shillings for the privilege. Despite this initial low cost, it was an extremely elite institution. Early subscribers included members of the Burd, Chew, Hamilton, Inglis, McCall, Mifflin, Penn, Peters, Plumsted, Powel, Shippen, Tilghman, Wallace, and Willing families. Although prominent Jewish families like the Franks and Levys also attended—reflecting Philadelphia’s religious diversity—the Society of Friends frowned on dancing, so leading Quaker families like the Logans, Morrises, Norrises, and Pembertons did not.

Sponsored Guests Only

Regardless of one’s wealth or social standing, it was never possible simply to appear at the Assemblies unsponsored. At times the invited guests were outsiders to the local social scene, however. In 1755, a group of Mohawk Indians joined the Assembly and performed a “scalping dance”; in 1768 the presence of the British Duchess of Gordon (Jane Gordon, c. 1748-1812) caused a stir. For outsiders and locals alike, the Assembly remained a “by invitation only” event throughout its history. At times, this exclusivity invited derision. For example, French refugee Moreau de St. Méry (1750-1819), no doubt chagrined at his own inability to secure an invitation in 1795, observed that there was considerable “snobbery in Philadelphia, where classes are sharply divided. This is particularly noticeable at balls.”

Once Philadelphia’s City Tavern was constructed at Second and Walnut Streets in 1773, the Assemblies were held there. Later, the event moved to Oeller’s Hotel, built at Sixth and Walnut Streets in 1791. At both sites, by day men met to talk business and politics. On the nights when Assemblies were held, however, women played important roles as dancers and arbiters of taste and behavior as they flaunted their genteel knowledge of formal dancing, their clothing and jewels, and, in some cases, their marriage potential.

Despite the importance of women at these events, from its beginnings, the Philadelphia Dancing Assembly operated under the aegis of a group of elite men, first called “directors” and later “managers.” These men (no doubt with the input of their wives, mothers, and sisters) laid down strict rules for the institution. In the eighteenth century, the Assemblies consisted of a series of balls held weekly throughout an entire winter social season, January through May.

The Politics of Dancing

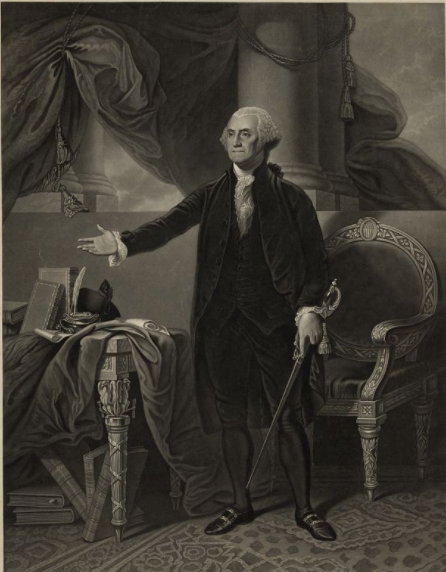

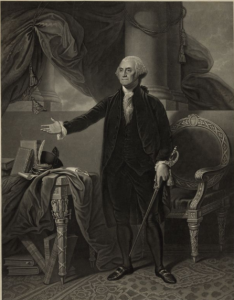

During the American Revolution and again in the 1790s, when Philadelphia was temporarily the capital of the young United States of America, the Philadelphia Dancing Assembly took on a political cast. Loyalists (and some of uncertain political leaning) who visibly supported the British during the occupation of Philadelphia in 1777-78 found their politics made them pointedly excluded from later Assemblies. As a notice in a local newspaper announced in 1780: “Such characters are either too detestable or too insignificant for Whig society. The company of those who were so insensible of the rights of mankind and of personal honour, as to join the enemies of their county in the most gloomy moment of the Revolution, cannot be admitted.” In the 1790s, when Philadelphia was the capital, President George Washington (1732-99) was a regular at the Philadelphia Dancing Assembly, which became the place for regular celebrations of Washington’s Birthday and one of the central gathering places of the “Republican Court” (as the political and social elites who attended George and Martha Washington’s presidential levees became known in the nineteenth century).

Dancing assemblies in other cities followed the model of Philadelphia but functioned more like debutante balls. The Baltimore Bachelors Cotillion began in 1796. In Boston, an Assembly had its heyday in the 1840s, and in New York, the Patriarch’s Ball formed in 1872 and had a female equivalent in the Ladies’ Assemblies, a series of winter balls run by a committee of women.

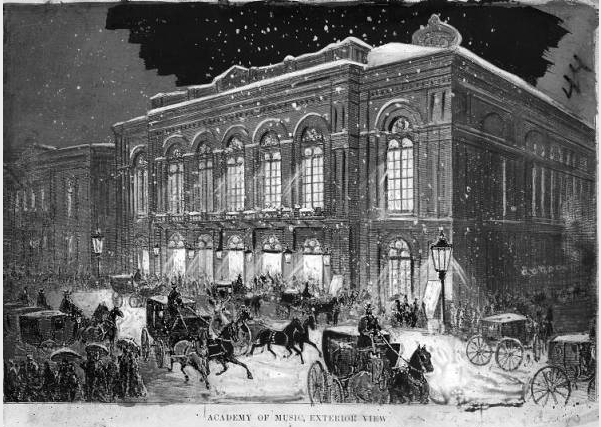

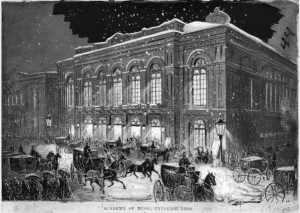

Philadelphia’s Assemblies were temporarily halted during the Civil War, but they resumed at war’s end in another of Philadelphia’s great cultural institutions: the Academy of Music, built in 1857 at Broad and Locust Streets. Dancing classes and clubs appeared in the nineteenth century to prepare young men and women for the Assembly. Dancing classes—held fortnightly—became their own kind of ritual and tradition. Such classes had their own junior recital balls—events that Godey’s Lady’s Book, in a March 1888 article on the Philadelphia social scene, called “a sort of step-great-grandchild of the Assembly.” A separate ball, the Philadelphia Charity Ball, was founded in 1884 as a debutante ball for prominent Philadelphian families. But while the Philadelphia Assembly has never been a “debutante ball,” members have debuted there, including Main Line socialite Hope Montgomery (1904-95).

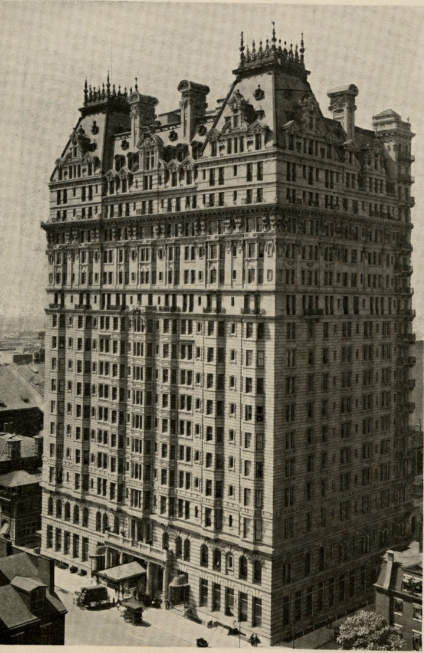

Over the course of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as the waltz replaced the minuet, and big bands were substituted for violin players, the Philadelphia Dancing Assembly continued to thrive as one of the—if not the—highlights of the Philadelphia social season. The tradition of preserving a social hierarchy around founding families continued. In 1904, the Assembly moved to the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel. Although another a wartime gap occurred between 1941 and 1946, the Assembly resumed after World War II ended and celebrated its bicentennial in 1948.

In the 1980s, the Assembly Ball saw a resurgence of popularity, which some observers attributed to the Reagan era’s emphasis on tradition and conservatism. The Assembly drew over 1,700 subscribers, and those who delayed in making their reservations found themselves turned down. Somewhat mysterious to the general public, the Assemblies of the early twenty-first century remained more exclusive than other “assembly balls” in cities like Cleveland, Boston, Baton Rouge, and Charleston. The Philadelphia Dancing Assembly retained a tradition of admission to membership by heredity according to the male line for a grand, annual, white-tie ball.

Zara Anishanslin is Assistant Professor of History and Art History at the University of Delaware and the author of Portrait of a Woman in Silk: Hidden Histories of the British Atlantic World (Yale University Press, 2016). Erica Lome served as research assistant for this essay. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History