Social Dancing

Essay

Dancing has been popular in Philadelphia since the city was founded, in spite of religious opposition, especially from Quakers. Far from succumbing to religious criticism, social dancing gained in importance as a way for socially ambitious Philadelphians to demonstrate their gentility. For most of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, well-to-do families gathered for formal balls in private houses and at private assemblies where subscribers paid for admission. Dancing gradually moved out of homes and clubs into hotels and restaurants that welcomed a broader spectrum of the population. Afternoon tea dances became popular in the hotels of Philadelphia and other large cities, and in the twentieth century social dance grew as a popular and even competitive pastime.

Dancing in early Philadelphia included country dances, which had long been popular in Britain among the laboring classes. These vigorous dances, with many variations, left many breathless by the end of the music. Imported to America by immigrants, country dancing was frowned on by the Philadelphia region’s Quakers and New England Puritans but popular elsewhere. Dancing among the higher classes was more staid and included formal events such as the Dancing Assembly of Philadelphia, founded in 1748-49. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, sons and daughters of socially prominent families in cities like Philadelphia, and those aspiring to higher social standing, studied with dancing masters from Britain and France, some of the latter fleeing from the French Revolution and bringing sophisticated French dances like the minuet and quadrille. The European dances they taught required frequent partner exchanges and allowed for only brief snatches of talk. These dancers allowed the sexes to be chaperoned, for they precluded intimate conversation.

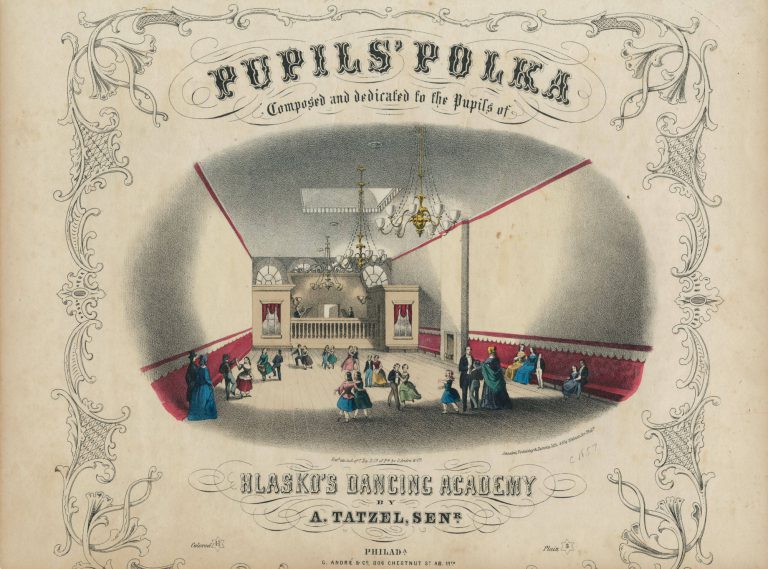

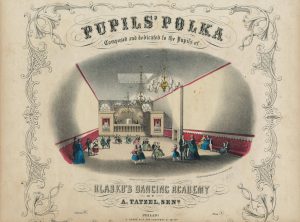

Enterprising dancing masters established academies to teach paying pupils and to host occasions where students could practice European quadrilles, cotillions, and reels. In the 1790s James Byrne (1756-1845), a one-time ballet master from London’s Covent Garden, along with dancing masters from France, taught at a dance academy at Oeller’s Hotel on Chestnut Street near Sixth. Others taught at Harmony Hotel on South Fourth Street, including Charles Durang (1793-1870), who in 1847 published a pocket-sized dance manual called Leaflets of the Ballroom to help a wider audience learn the essentials of proper dancing.

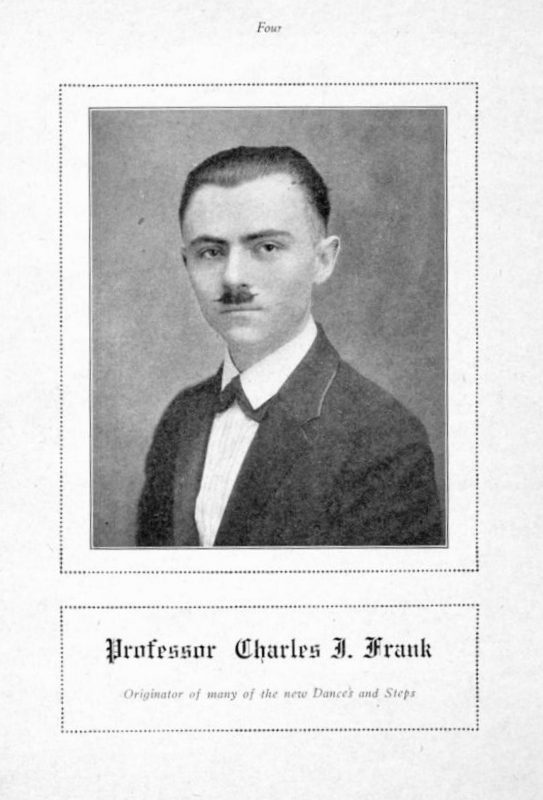

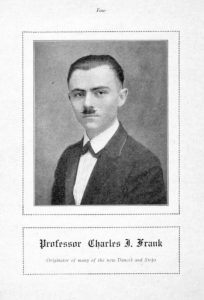

The waltz, imported from Europe at the beginning of the nineteenth century, required what many thought was a dangerously close embrace. Through much of the century, dancing in close hold was not considered acceptable among the respectable classes. However, among young single urban workers, whose earning brought them independence, dance halls across Philadelphia and other urban centers began to take hold. In the mid-nineteenth century a craze for the polka took hold among all classes. Polka sheet music began to be published in Philadelphia in 1844. Remade in Paris to smooth its rough country edges, the dance became the rage for several years. Its vigorous movements preclude intimacy. By the end of the nineteenth century, the waltz began to be more widely accepted as a way for couples to engage in intimate conversation away from the prying eyes of chaperones. In the early twentieth century, Charles J. Frank opened a dance academy on Walnut Street, where he taught the waltz and other new crazes, such as the two-step and the foxtrot. In 1922, Frank published a book of social dance steps for devotees to learn at home.

Nevertheless, anti-dancing sentiment remained strong into the early years of the twentieth century. In an 1892 book titled From the Ballroom to Hell, T. A. Faulkner, a Los Angeles dancing master, declared, “It is a startling fact but a fact nevertheless, that two-thirds of the girls who are ruined, fall through the influence of dancing.” Faulkner claimed to have interviewed two hundred prostitutes, 186 of whom said they had been ruined because of social dancing, particularly the waltz. His book published in Chicago seems to have fallen on mostly deaf ears, except for those who already disapproved.

Dancing: Good for Business

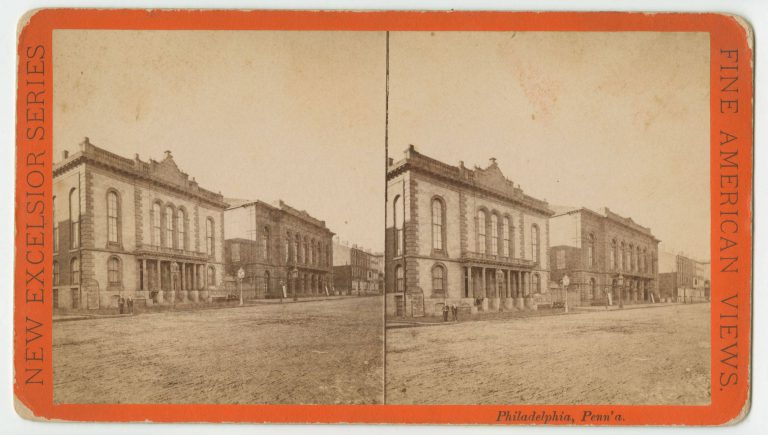

Industrialization during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries produced a growing class whose incomes allowed for entertainment of all kinds. The introduction of ragtime music, which was associated with dancing from its inception in the 1890s, led restaurant owners to realize that dance could increase their business, and they started to build dance floors followed by halls devoted to social dance. African Americans played an important role in popularizing ragtime through the introduction of dance competitions. In 1892 a largely white audience gathered in Horticultural Hall (then on South Broad Street) to witness a “cake walk,” a form of ragtime competition. This African American dance style performed to syncopated rhythms became wildly popular, helping fuel the emergence of ragtime music in both white and Black communities.

Some of the most popular dances like the swing and jitterbug started with African Americans. Dance teachers, feeling a need to keep ballroom respectable, went to great lengths to distance such dances from their Latin American and African American origins. Instructors resisted improvisations that altered their prescribed techniques and standardized steps. The Philadelphia Association of Teachers of Dancing formed in the 1890s to promote standard dance forms for both studios and social dance parties. In the long run, their efforts at control failed as more and more diverse groups took up social dancing and adopted individual styles.

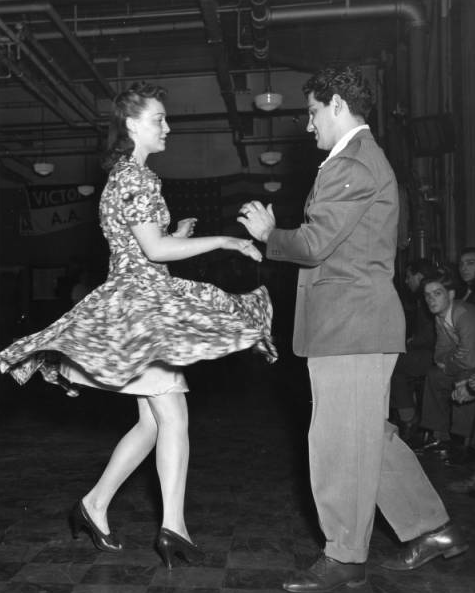

By the advent of the First World War, in Philadelphia, as in most large American cities, the popularity of the waltz and of ragtime music meant that social dance had become the center of social life for the working class. Middle-class young men and women also escaped from the confines of their families to join them. During the summer months of the early 1920s, Philadelphia police and firemen’s bands provided free live music every Thursday evening at Logan Square (later Logan Circle) for social dancing. A competition that became known as the Dance Contest on the Parkway awarded cash prizes to the most accomplished couples. Philadelphians practiced dances like the waltz, foxtrot, and tango to prepare for these weekly events, which discouraged any wilder jazz-inspired dances. Such dances were popular in the growing Black communities in the city and among whites who were brave enough to go “slumming” and join them.

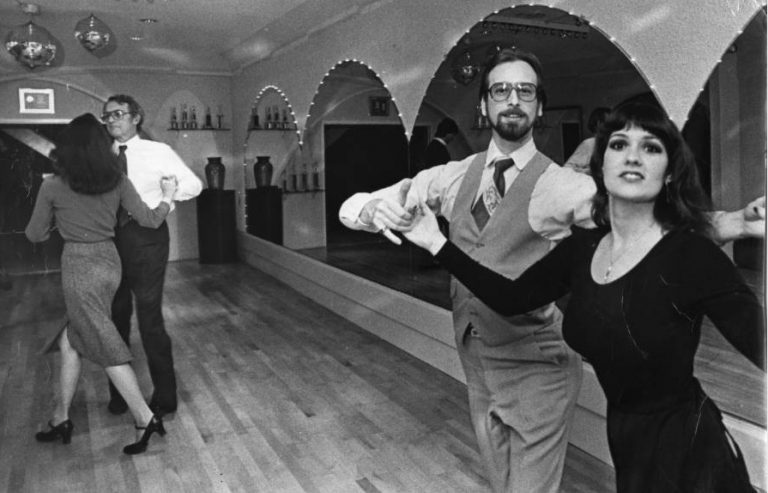

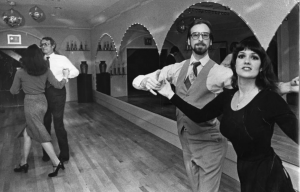

Responding to the high level of interest, national chains of dance studios came to Philadelphia as to other U.S. cities, starting in 1925 with Arthur Murray (1895-1991) and his wife Kathryn (1906-99) and expanding in 1947 when Fred Astaire (1899-1987) started his chain. At one time, almost all ballroom dancing was taught in the chains. However, because of the unscrupulous nature of chain operators and their devotion to selling lessons rather than building relationships, independent studios re-entered the market in the 1950s. Independents gained popularity by paying attention to relationships, for example by noticing their customers’ hair and clothes and even bestowing hugs and kisses upon their arrival.

American Bandstand

While studios and ballrooms continued to teach dancing in close hold, the youth culture of the 1960s epitomized by American Bandstand turned to more open dances like the twist and the jive. Many studios that provided ballroom lessons fell on hard times despite a brief respite when the hustle, which started in the South Bronx among Puerto Rican immigrants, became popular as a result of the movie Saturday Night Fever (1977).

While not enjoying the mass support of a century earlier, ballroom dancing in the early twenty-first century maintained many devotees in the city, the suburbs, and the rest of the United States. Furthermore, devotees of the art had many options. Studios ran the gamut from training top professional and amateur students in mixed places offering a variety of lessons—competition, wedding dance, and social dance–to informal gathering places like the Atrium Dance Studio on the edge of Camden, New Jersey. Its owner, Barbara Capaldi, once taught at a nearby Arthur Murray studio until she realized that she could not afford to take lessons there herself. She founded her studio in 2001 and began organizing lessons and parties most nights of the week and on weekend afternoons. On Sunday afternoons, she introduced a ballroom party, where attendees could receive group lessons, eat dinner, and dance for about three hours—all for $15.

Men and women could take lessons, attend group classes, or go to dance parties in Philadelphia and its suburbs every night of the week in dedicated spaces or rented spaces in local YMCAs and other places with low rents. In the Philadelphia area, a dance newsletter in 2016 regularly advertised around fifty places per week for dance mixed ballroom and Latin dancing; ten for various types of swing; twenty for Argentine tango; and nine places to dance hustle. The arrival of numerous immigrants from Eastern Europe, particularly in the Soviet Union, spurred demand for lessons and provided an influx of qualified teachers from cultures where dance is revered. In the Philadelphia area, several studios opened to teach mostly Russian immigrants, especially in the Northeast.

At social dance parties, rotation dances gained popularity as a way for all to dance regardless of skill and as an opportunity to see who could dance well and who might be a good partner later in the evening. In the rotation dance, men line up on the outside and women on the inside. The first man has to dance with the first woman. They go around the floor and he drops her off, moves to the front and dances with the next available woman, and so on. As one man dancing at the regular Saturday night dance in the Church on the Mall in Plymouth Meeting remarked in 2008, “It’s like having a one-minute affair. I dance around the floor with someone for a minute and then I dump her. No hard feelings.”

Silver Linings Playbook

The most dedicated students pursued dancing more intensively, spending over $100 per lesson, taking many lessons a week, and competing in expensive competitions offered every weekend all over the country. These competitions, known in the field as Dancesport, provided the model for the television show Dancing with the Stars (first broadcast in 2005), on which professional dancers performed with their students. In the film Silver Linings Playbook (2012), the Benjamin Franklin House in Center City Philadelphia served as the site of a dance competition, but no such event was ever held there.

Ballroom and Latin dance evolved as highly gendered activities. Although a number of gay men became the top Latin dancers worldwide, they stayed largely in the closet until the late twentieth century. Indeed, because male dancers were frequently assumed to be gay, they often sought to demonstrate their heterosexuality by joking about it. This changed, however, with the advent of same-sex dance competitions. In Philadelphia, for example, the annual Liberty Dance Challenge began in 2008 and required all partners must be of the same sex. Men in the competition typically wore matching outfits, often elaborately trimmed in lace and with hanging arm floaters of the type worn by women competing in ballroom. They frequently took turns taking the lead. Women, on the other hand, performed in more gendered ways, with one woman being the lead and the other the follower. Sometimes both wore pants, sometimes both dresses, and sometimes the lead wore pants and the follower a dress.

Social dance continued to hold appeal in the modern world, offering the warmth, intimacy, and connection of a relationship yet not requiring long-term commitment. As one woman said in 2006 about the competition circuit: “I am divorced, I work long hours and have no time to look after a husband. I go [to competitions] and am surrounded by handsome young men. I love the high heels, the clothing, the glamour, and the fuss I receive. Then I go home, put it back in the closet, put on my business suit, and go back to work.” In the early decades of the twenty-first century, social dance remained vibrant in Philadelphia and its suburbs.

Julia A. Ericksen is Professor Emeritus of Sociology at Temple University, a competitive ballroom dancer, and author of Dance with Me: Ballroom Dance and the Promise of Instant Intimacy (NYU Press, 2011). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Dance Yourself Fit in Germantown this weekend (WHYY, April 26, 2013)

- Philly students learn life skills through ballroom dance competition (WHYY, June 3, 2013)

- Video: Russian novel-in-verse set to music and ballroom dance at Princeton (WHYY, May 31, 2012)

- Dancing the tango at Philadelphia's Free Library (WHYY, July 24, 2013)