Jazz

Essay

Jazz began to emerge as a distinct musical style around the turn of the twentieth century, a merging of two vernacular African American musical styles—ragtime and blues—with elements of popular music. New Orleans, the “cradle of jazz,” was the most important city in this process, with Chicago and New York playing particularly significant roles in the 1920s and 1930s. By the mid-twentieth century Philadelphia had become an important jazz center and a key training ground for influential jazz musicians. During its jazz heyday of the 1940s–1960s, Philadelphia produced an extraordinary number of leading jazzmen, several of whom became transformative figures in jazz history.

Jazz was created primarily by Black musicians in its early years, but white musicians adopted the style early on and made contributions to its development. It was, in fact, a white New Orleans group, the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, that made the first jazz recordings in 1917.

As jazz gained national popularity in the late 1910s, many of its early practitioners began to leave New Orleans for the cities of the North. Chicago and New York were primary destinations, but Philadelphia also welcomed some of these jazzmen. Trumpeter Freddie Keppard (1889–1933), a key early figure, had a successful extended gig in Philadelphia in 1917. His former New Orleans bandmate, clarinetist George Baquet (1881–1949), moved to Philadelphia in 1923 and remained active in the city’s music scene for the rest of his life.

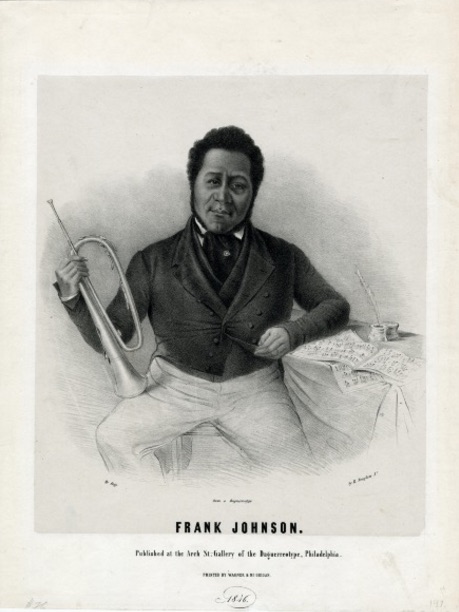

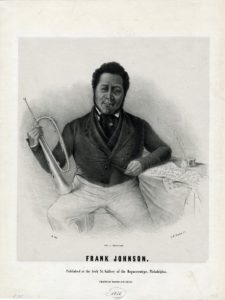

Frank Johnson, Bandleader and Composer

These musicians came to a city with a long tradition of African American popular music. Frank Johnson (1792–1844) was a well-known African American bandleader and composer in early nineteenth-century Philadelphia who led bands for several of the city’s military units and was the favored music director for the balls of the city’s social elite. Johnson was the first African American to have his music published (in 1818) and the first American, Black or white, to lead a musical ensemble on a tour of Europe (in 1837). Johnson sometimes enlivened popular dance tunes with varied rhythms and melodies, an early example of fusing African-derived rhythmic and melodic elements with European-based harmonic and formal structures that would later give birth to jazz.

A century later, in the 1920s and 1930s, Black Philadelphia bandleaders Charlie Gaines (1900–87), Frankie Fairfax (1899–1972), and others led dance bands in the swing style of jazz then gaining popularity. Philadelphia saw a huge increase in its African American population in this period as a result of the Great Migration, the mass movement of Blacks out of the rural South to the cities of the North. These newcomers brought their southern musical traditions with them, joining urban Black musicians whose families had been living in the city for generations. The result was a particularly vibrant African American musical culture, one that would nurture the careers of numerous important jazz musicians. In 1935 some of these musicians established Local #274 of the American Federation of Musicians, the Philadelphia Black musicians’ union that would serve as a focal point of the city’s jazz community until its dissolution in 1971.

Dizzy Gillespie, Bebop Pioneer

Among the noted jazz musicians who came to Philadelphia from the South in the 1930s were bebop pioneer Dizzy Gillespie (1917–93) and rhythm and blues star Louis Jordan (1908–75), both of whom settled in Philadelphia early in their careers and honed their skills for a few years before moving on to New York City, the great jazz mecca. Others spent longer periods in Philadelphia. Saxophonist John Coltrane (1926–67), one of the most influential figures in jazz history, moved to Philadelphia from North Carolina in 1943 at the age of seventeen, joining native-born Philadelphians such as saxophonists Jimmy Heath (b. 1926) and Benny Golson (b. 1929), pianist McCoy Tyner (b. 1938), trumpeter Lee Morgan (1938–72), and others in the city’s especially fertile midcentury jazz scene. They developed their craft through informal jam sessions, gigging in local clubs and dance halls, and occasionally touring with traveling groups. Other musical luminaries nurtured in the rich Philadelphia jazz tradition of this era include Clifford Brown (1930–56), Percy (1923–2005) and Albert “Tootie” Heath (b. 1935), Bobby Timmons (1935–74), “Philly” Joe Jones (1923–85), Jimmy Smith (1928–2005), Jimmy Garrison (1934–76), Reggie Workman (b. 1937), Kenny Barron (b. 1943), and Archie Shepp (b. 1937).

Although jazz has traditionally been a male-dominated music, women were part of the Philly jazz scene as well. Organists Trudy Pitts (1932–2010) and Shirley Scott (1934–2002) were among those who contributed to the city’s significant jazz organ tradition. Philadelphia has also been home to a long line of important female jazz and blues vocalists, including Ethel Waters (1896–1977), who was born in nearby Chester, Pennsylvania, and began singing in Philadelphia in the 1910s; Bessie Smith (1894–1937), who moved to Philadelphia in 1923 at the beginning of her very successful recording career; and Billie Holiday (1915–59), who, although raised in Baltimore, was born in Philadelphia and performed in the city often throughout her career.

Philadelphia was also home to a thriving white jazz community. While Black and white musicians might play together informally, integrated bands were uncommon prior to the mid-twentieth century. Violinist Giuseppe “Joe” Venuti (1903–78) and guitarist Eddie Lang (real name Salvatore Massaro, 1902–33) were childhood South Philadelphia friends who played with some of the nation’s top white bands and made a series of influential duo recordings in the 1920s and 1930s. Charlie Ventura (1916–72), Buddy DeFranco (1923–2014), Red Rodney (1927–94), and Gerry Mulligan (1927–96) are some of the famous white jazz musicians who came out of the mid-twentieth-century Philly jazz scene.

“Quaker City Jazz”

Jan Savitt (real name Jacob Savetnick, 1907–48) played a more polished style of jazz. A Russian immigrant violin virtuoso, Savitt gave up a promising career with the Philadelphia Orchestra to lead a nationally popular swing band. Jan Savitt and His Top Hatters served for a time as the staff orchestra for KYW Radio, where one of their theme songs was “Quaker City Jazz.” Savitt was one of the first major white bandleaders to hire an African American singer when he began featuring local singer George “Bon Bon” Tunnel (1912–75) in 1937. Another Philadelphia big band leader of Russian Jewish heritage was Howard Lanin (1897–1993), the “King of Society Music,” who led popular ensembles for over seventy years, specializing in dance music and “sweet jazz” for Philadelphia high society.

During the heyday of Philadelphia jazz in the 1940s through 1960s, the city was alive with jazz clubs and home to many of the music’s leading figures. There were jazz clubs and dance halls in many areas of the city, with particularly important concentrations in the area surrounding South Broad Street in South Philadelphia and along Columbia (later Cecil B. Moore) Avenue in North Philadelphia (the latter came to be known as “the Golden Strip”). Better-known touring bands played the theaters, either Black theaters such as the Royal, Lincoln, or Pearl, or, in the case of the biggest name bands, both Black and white, the Earle Theater, the ornate showplace at Eleventh and Market Streets. Many Philadelphia jazzmen who came of age in the 1930s and 1940s saw Duke Ellington (1899–1974), Benny Goodman (1909–86), and their other musical idols at the Earle Theater.

By the late 1960s, changes in public taste and the music business signaled an end to the golden age of jazz in Philadelphia. The city remained an important jazz hub in the early twenty-first century—still home to a number of jazz clubs and still producing significant jazz musicians—but was no longer the preeminent jazz center it had been. The local audience became smaller and more specialized and much of the work of presenting jazz was carried out by nonprofit organizations such as the Philadelphia Clef Club of Jazz and Performing Arts, Jazz Bridge, Philadelphia Jazz Project, Lifeline Music Coalition, and Ars Nova Workshop. These groups, together with local clubs and the city’s many jazz musicians and fans, continued the rich tradition of jazz in Philadelphia.

Jack McCarthy is a music historian who regularly writes, lectures, and gives walking tours on Philadelphia music history. A certified archivist, he is currently directing a project for the Historical Society of Pennsylvania focusing on the archival collections of the region’s many small historical repositories. He has served as consulting archivist for the Philadelphia Orchestra and the 2014 radio documentary Going Black: The Legacy of Philly Soul Radio and gave several presentations and helped produce the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s 2016 Philadelphia music series “Memories & Melodies.” (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Coltrane’s sax joins Smithsonian jazz collection (WHYY, March 26, 2014)

- Nation's first gay jazz festival, OutBeat, will debut in Philadelphia (WHYY, May 7, 2014)

- Woodmere kicks off season of jazz in Chestnut Hill (WHYY, February 18, 2016)

- A night in the life of Philly’s jazz scene (WHYY, April 7, 2016)

- Grooming the next generation of jazz musicians in Delaware (WHYY, June 21, 2016)

- Revitalization stirs up memories of a time Sharswood pulsed with all that jazz (WHYY, August 30, 2016)

Links

- Jazz in Pennsylvania (ExplorePaHistory.com)

- Big Band Jazz in Philadelphia (The PhillyHistory Blog)

- Ethel Waters - The Collection (Internet Archive)

- Trudy Pitts and 'Mr. C,' Partners in Music (NPR)

- John Coltrane - A Man Called Trane (Internet Archive)

- Riffing on Philly Jazz History (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)