Dispensaries

Essay

Free clinics known as dispensaries served the “working poor” of European, British, and American cities from the eighteenth through the early twentieth centuries. Paid or volunteer physicians saw patients on site or at their homes in the dispensary’s district, caring for both minor ailments and more serious diseases. The Philadelphia Dispensary for the Medical Relief of the Poor, considered the nation’s first, opened in 1786. By the late nineteenth century, a disorganized assortment of dispensaries large and small served the Philadelphia region’s growing population of new immigrants.

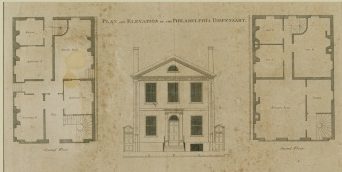

The Philadelphia Dispensary opened in rented space but was able to erect a handsome building on Fifth Street between Chestnut and Walnut in 1801. Both Quaker and non-Quaker citizens supported the enterprise, originally headed by the admired Episcopal Bishop William White (1748-1836) and administered by other prominent Philadelphians, particularly members of the Wistar/Wister family. Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) headed the first subscribers, who could each list two persons for free care. Many prominent physicians served as regular dispensary doctors or consultants. An employed apothecary prepared the pills, tinctures, salves, and the like, which almost all patients received: the name “dispensary” well fit the function. The Philadelphia Dispensary also offered inoculation against smallpox. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, the dispensary cared for large numbers of African Americans, and then Irish following their increasing immigration in midcentury.

Overwhelmed with clientele, the Philadelphia Dispensary in 1816 made loans to support the founding of the Northern Dispensary, serving the Northern Liberties into Kensington, and the Southern Dispensary (chartered in 1817) for Southwark, Moyamensing, and Passyunk. These functioned very much like the parent institution. Eventually, dispensaries could be found in the various townships and neighborhoods. For example, the Germantown Dispensary (later Germantown Dispensary and Hospital) opened modestly in one room in 1864, an initiative of the prominent physician James. E. Rhoads (1828-94). The Camden City Dispensary was founded in 1866, with members of New Jersey’s prominent Cooper family enrolling as “life members” (subscribers). Norristown Hospital and Dispensary was among facilities in the region to offer both inpatient and outpatient services; founded in 1889, it soon changed its name to Charity Hospital, and later Montgomery Hospital.

Specialty Dispensaries

The evolution of Philadelphia’s various dispensaries reflected changes in the region’s population and in medicine. The Southern Dispensary in Philadelphia, for example, saw increasing numbers of immigrants from Eastern Europe and Italy as well as African American migrants from the South during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. With the growth of specialization in medicine, specialty dispensaries arose for skin diseases, eye and ear problems, pediatrics, and for the ubiquitous and deadly tuberculosis. The older dispensaries organized their clinics by categories of disease. Nonetheless, the major dispensaries of Philadelphia remained mainstays of outpatient medicine for ailments such as coughs and catarrhs (colds), “rheumatism,” dyspepsia, and diarrhea and earaches among children. Dispensaries in industrial areas also looked after cuts, burns, and various injuries not needing hospitalization or major operations.

Something like a dispensary mania surged in the second half of the nineteenth century. The strong presence of the alternative therapeutic practice homeopathy in the city led to homeopathic dispensaries. The House of Industry and the College Settlement also offered dispensaries. Jewish anarchist physicians opened their Mt. Sinai Dispensary at 236 Pine Street in 1900. The major hospitals spawned dispensaries, as did some of the medical schools.

Medical education had played a major role at dispensaries from the beginning, since young doctors used them to gain experience. Alumnae of the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania founded an outpost, the Barton Dispensary (named for a founder), on Third Street in South Philadelphia in 1895; it later moved, when the college did, to East Falls. The “Medical Society for Self-Supporting Women” for some years in the late 1880s conducted an evening dispensary for working women, with women physicians as staff. In 1883 surgeon John B. Roberts (1852-1924) and others opened the Philadelphia Polyclinic and College for Graduates in Medicine at Thirteenth and Locust Streets. This “short course” school for those already holding the M.D. aimed at providing practical experience sometimes lacking in conventional medical schools. Instruction depended largely on the institution’s dispensary practice, although later, at Lombard Street between Eighteenth and Nineteenth, it added a hospital (later known as Graduate Hospital). While many Philadelphia physicians practiced at a dispensary sometime in their careers, and some even founded one, other physicians thought the proliferation was getting out of hand. They suspected that persons capable of paying a fee to a private practitioner nonetheless would seek care at a dispensary–what was referred to as “dispensary abuse” or more broadly, “charity abuse.” This tension arose in other cities as well.

Clinics Evolve

Over the course of the twentieth century, other forms of free clinics gradually replaced dispensaries. A 1929 report on medical facilities in Philadelphia listed seventy-one dispensaries, almost all of them outpatient practices of hospitals, medical schools, or other organizations. Only the Northern Dispensary and the Southern survived as independent entities. The original Philadelphia Dispensary had merged with the outpatient services of Pennsylvania Hospital in 1922. By the 1940s, health clinics conducted by the Philadelphia Department of Health assumed some of the work once done by the city’s dispensaries. Outpatient departments of hospitals and medical schools expanded (and eventually could gain reimbursement with the advent of Medicare and Medicaid in 1966). Nonprofit agencies such as the Public Health Management Corporation also opened free-standing clinics, including the Mary Howard Health Center, managed by nurses and serving Philadelphia’s homeless population. Into the 1980s and 1990s, community-minded medical students and faculty physicians at Hahnemann Medical College and the Medical College of Pennsylvania (the former Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, coeducational as of 1970) reinvented the free neighborhood night clinic. Surprisingly, the term “dispensary” resurfaced in 2017 with a novel connotation—the place to go for medical marijuana.

Philadelphia’s dispensaries of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including the nation’s first such institution, served basic health needs of the poor, particularly first-generation immigrants, though their educational function may have been at times exploitive. Various free or low-cost clinics continued to operate in the early twenty-first century, demonstrating a persistent need despite the availability of health insurance and the federal Medicare, and Medicaid programs.

Steven J. Peitzman is Professor of Medicine at Drexel University College of Medicine. His historical work includes the book A New and Untried Course: Woman’s Medical College and Medical College of Pennsylvania, 1850–1998 (Rutgers University Press, 2000) and articles about medicine and medical education in Philadelphia and Germantown. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History