Mexican-American War

Essay

Despite taking place in the American Southwest and Central America, the Mexican-American War (1845-48) had significant ties to the Philadelphia area. As one of the most populous urban centers in the country, the Delaware Valley became a hotbed of activity for one of the most controversial wars in American history.

War between the United States and Mexico followed the admission of Texas as the twenty-eighth state of the United States in December 1845. This exacerbated preexisting tension with the Mexican government, which never recognized Texas independence, American annexation of Texas, nor the proposed border of the new state at the Rio Grande River. After an armed clash between U.S. forces led by General Zachary Taylor (1784-1850) and Mexican troops in the disputed area between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande, Congress declared war on Mexico on May 13, 1846, and authorized President James K. Polk (1795-1849) to call up fifty thousand volunteers to join the existing U.S. Army.

In Philadelphia and elsewhere, the controversy surrounding the coming and course of the Mexican-American War illustrated the widening divide in American society over the issues of territorial conquest and the expansion of slavery. Initially, support for the war was strong in the mid-Atlantic states, and Philadelphia’s historic ties to the American Revolution made it a centerpiece for pro-war patriotism by politicians and cultural figures who viewed Manifest Destiny as the legacy of American independence. The Philadelphia North American, a “penny press” newspaper owned by George R. Graham (1813-1894), reported news from Mexico and supported “Mr. Polk’s War” in editorials. However, Philadelphia’s active abolitionist community opposed the war as a vehicle for expanding slavery into new territory. In June 1846, The National Anti–Slavery Standard, published in Philadelphia, strongly opposed the war based on its abolitionist views against expansion of slavery into the West.

The war was equally controversial in New Jersey and Delaware. In New Jersey, a strong Whig Party presence in state politics made unified action difficult. In October 1847, a convention of New Jersey Whigs condemned the Polk administration’s drive for territorial annexation. Niles’ National Register reported that their resolutions “strongly denounced the present national administration for violations of the liberties of the people and interests of the Union, especially in having made war without consulting the people or their representatives, and that too, for party purposes.” This sentiment was common across New Jersey. When New Jersey Governor Charles C. Stratton (1796-1859) responded to President Polk’s call to organize volunteers for service, the turnout was so meager that only a New Jersey Battalion of Volunteers could be formed, not a regiment. In Delaware, opposition to the war ran so strong that only a dozen residents volunteered to serve.

During the opening stages of mobilization, Philadelphia joined other cities in holding a pro-war rally, but this fervor was not universal. In response to impassioned opposition speeches delivered by Whig politician Henry Clay (1777-1852) in the autumn of 1847, anti-war rallies took place in Philadelphia and Trenton, New Jersey.

The “Killers” in the Ranks

Following the declaration of war, Pennsylvania Governor Francis R. Shunk (1788-1848) called for forming six regiments to serve in the U.S. Army. In contrast to the tepid response in New Jersey and Delaware, patriotic enthusiasm quickly satisfied the quotas, and several full companies had to be turned away. Recruits from the Keystone State were organized into the First and Second Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiments. Of the ten companies constituting the First Regiment, six hailed from Philadelphia, including the City Guards of Philadelphia, The Philadelphia Light Guards, and the Cadwalader Grays. The Second Regiment became home to Company F, known as the Philadelphia Rangers.

Along with the patriotism that motivated Philadelphia men to serve, the disorder and violence that had been hallmarks of Philadelphia during the 1830s and 1840s also traveled west with the volunteers who mustered in Harrisburg and then proceeded to Pittsburgh en route to Mexico. In Pittsburgh, soldiers from Company D (The City Guard) invaded a local theater in an incident that ended in a violent clash with police. This riotous behavior continued later New Orleans, where a soldier claiming membership in the notorious Philadelphia “Killers” gang attacked citizens and destroyed property across the city. Later, a faction of the Killers intimidated Company D’s commanding officer, Captain Joseph Hill, who temporarily fled the regiment in April 1847. Another veteran of Philadelphia street violence led the Pennsylvania volunteer regiments after their transport down the Mississippi River and across the Gulf to Lobos, Mexico, where they landed in February 1846. Major General Robert Patterson, a former Pennsylvania militia commander, had led troops against rioters during the destruction of the Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia in 1838. In Mexico, he commanded the Second Division of a brigade led by Brigadier General Gideon J. Pillow (1806-1878), which took in the Pennsylvania volunteers.

The Pennsylvania Volunteers in Mexico

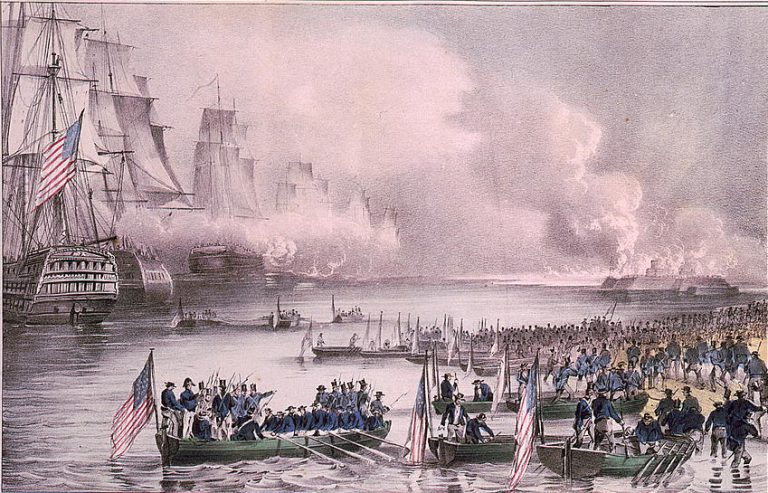

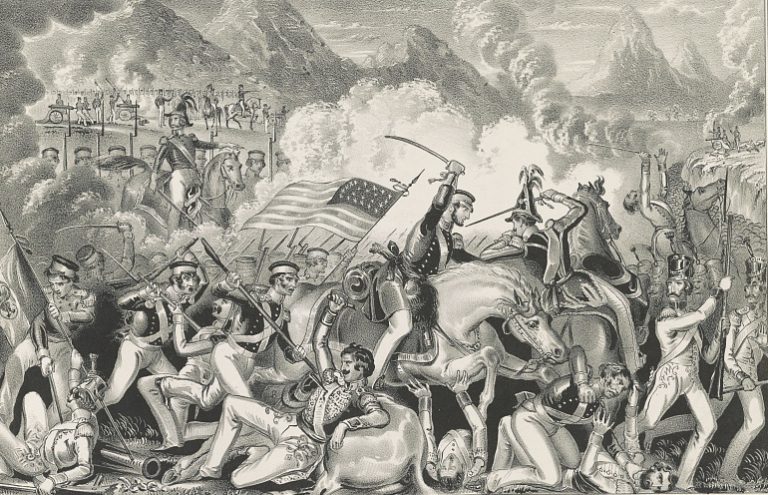

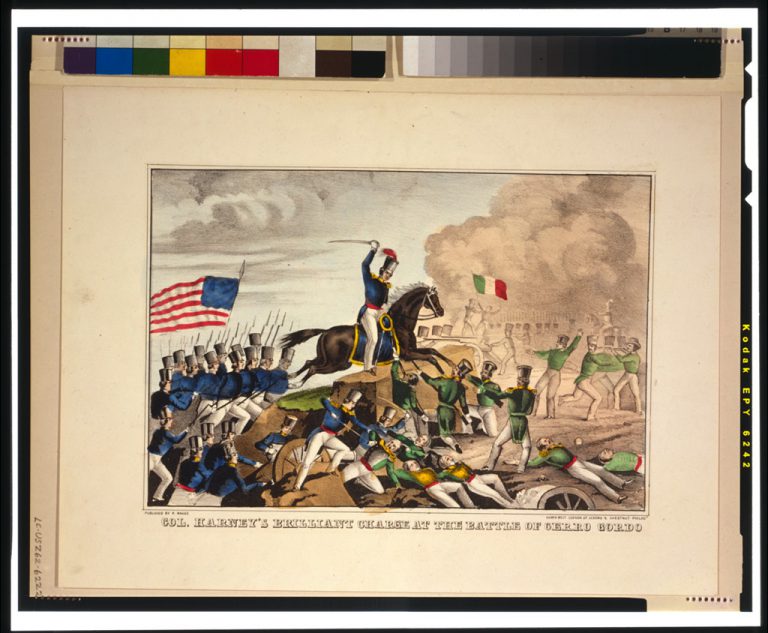

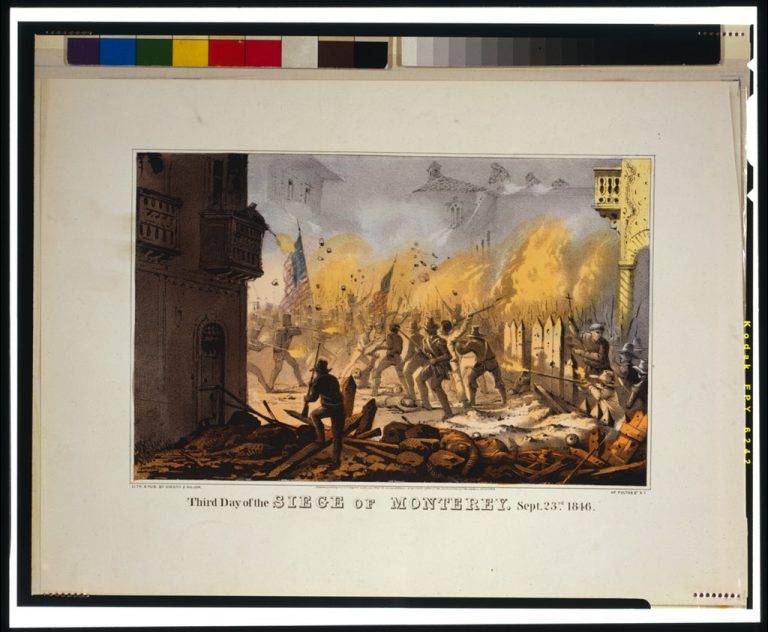

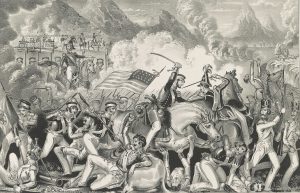

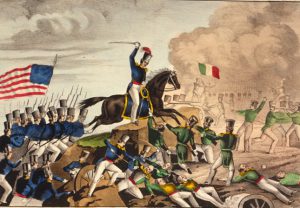

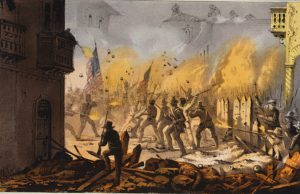

The fighting men from Philadelphia saw their first significant combat at the Siege of Veracruz in March 1847. In the thunderous twenty-day siege, the Pennsylvania regiments lost the service of fifteen soldiers to enemy cannon fire, including three who were killed. After the fall of Veracruz, the regiments moved into the Mexican interior and saw action again in April at the Battle of Cerro Gordo as part of an assault on Mexican artillery at Jarero, south of the Mexican encampment near Vasquez. Despite the ferocity of the engagement, the regiments suffered few casualties. For the next two months, they continued inland toward Mexico City, fighting guerillas, the elements, and disease.

In September 1847, the Pennsylvania Regiments were split by General Winfield Scott (1786-1866) to prepare for the assault on Mexico City. While three of the Philadelphia companies were reassigned to garrison duty at Puebla, the Reading Artillery of Company A and the Philadelphia Rangers of the Second Regiment proceeded with the main army toward Mexico City. Both companies saw heavy fighting at close range with the Mexican defenders. In two days of combat, the Second Regiment suffered its worst losses of the conflict with eight men killed and eighty-nine wounded.

Mexican troops flushed out of Mexico City and led by General Antonio López de Santa Anna (1794-1876) next attacked Puebla, where the Philadelphia remnant of the First Regiment had been stationed. A nearly month-long siege ensued began in September 14, 1847. Forces under Lieutenant-Colonel Samuel Black (1816-1862), a Pittsburgh native and future Pennsylvania congressional representative, faced repeated assaults and dwindling supplies until Santa Anna withdrew his troops on October 12. The Siege of Puebla was not only the Pennsylvanians’ finest performance, it was also the most costly. The First Regiment suffered fifty-five casualties with twenty-one men killed in action. In December 1847, the survivors marched to Mexico City, where they reunited with the Second Regiment to much fanfare and celebration.

Philadelphia-area soldiers also served in areas of the war other than Mexico. A veteran of the War of 1812, Rear Admiral William Mervine (1791-1868), commanded the USS Savannah in the Pacific, and his Marine detachment captured the city of Monterey in July 1846. Samuel Francis Du Pont (1803-65) of the famed DuPont family of Delaware commanded the blockade of California and achieved the rank of rear admiral. Future U.S. senator from New Jersey Commodore Robert Stockton (1795-1866) was instrumental in the capture of Monterey and Pueblo de Los Ángeles in California. Between July 1846 and January 1847, Stockton served as military governor of California.

In Mexico, Philadelphia native and Brigadier General Persifor Frazer Smith (1798–1858) served as military governor during the occupation of Mexico City, when duty for the Pennsylvania volunteer regiments consisted of a mixture of drill, boredom, and sporadic chaos as Mexican guerilla units harassed U.S. forces. When U.S. troops withdrew on March 6, 1848, the regiments’ long journey home took them from Mexico back to New Orleans, then up the Mississippi River and Ohio Rivers to Pittsburgh, where they arrived on July 11, 1848. The Pittsburgh units mustered out of service quickly, but the Philadelphia companies resolved to end their service at home. Between July 27 and August 5, parades, speeches, banquets, and community events across the Delaware Valley marked their return. Of the 2,415 men who served in the Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiments, 477 died in Mexico or in transport. Fifty-two were killed in combat. New Jersey’s volunteers saw little combat in Mexico and returned to the Garden State in July 1848. Delaware’s volunteers, who took part in the Battle of Huanmantla in October 1847, returned in August 1848, having suffered a single casualty.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican-American War on February 2, 1848, and expanded the territory of the United States by 525,000 square miles. However, the costly victory, earned after two years of ferocious combat, exacerbated the simmering tensions throughout the country. Volunteers from Philadelphia and the surrounding region participated in the military actions while local citizens debated the war’s political and moral ramifications, making Philadelphia and the Delaware Valley a microcosm of the conflict.

William V. Bartleson is an independent scholar of military history who has worked with the New Jersey National Guard Militia Museum and the Center for Veterans Oral history. He is a member of Phi Alpha Theta. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Geary Family Papers (Historical Society of Pennsylvania Digital Library)

- A Forgotten American Hero: Captain John B. Page (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- The Mexican-American War in a nutshell (National Constitution Center)

- Santa Anna's Proclamation, published in Philadelphia, 1847 (Library of Congress)

- The Storming of Chapulapec, Song of War, published in Philadelphia (Library of Congress)

- A Guide to the Mexican War (Library of Congress)

- The U.S.-Mexican War (PBS)

- Mexican-American War and the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo (National Park Service)