Bridgeton, New Jersey

Essay

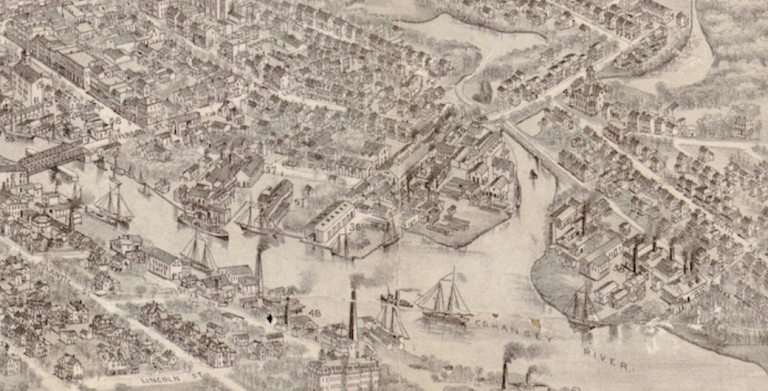

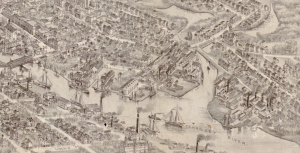

Bridgeton, the governmental seat of Cumberland County, originated in the late seventeenth century as a fording place at the upper tidal reach of the Cohansey River, a tributary of the Delaware Bay. Located seven direct miles from the bay (though twenty by meandering river), and about forty miles south of Philadelphia, Bridgeton drew on water power and water transportation for its growth throughout the nineteenth century. These assets became obsolete in the twentieth century, but Bridgeton’s strong industrial base produced continued prosperity through the first three-quarters of the century. Starting in the 1970s, however, industry receded as an economic base, in part because of Bridgeton’s distance from the interstate highway system. Bridgeton nevertheless remained a regional center for the surrounding agricultural area and attracted a growing population of farm and nursery workers who sustained civic vitality despite the town’s greatly reduced tax base.

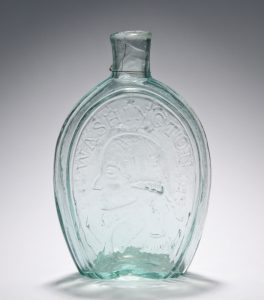

Cumberland County, in the New Jersey Coastal Plain, consists of unconsolidated sediments formed during the Cretaceous period. The layers of sand, silt, and clay were deposited as the sea level fluctuated during the Tertiary period; the Cohansey Formation, consisting of layers of quartz within thin layers of clay and gravel, covers the entire county and was laid down late in the Tertiary age. The widespread Bridgeton Formation (medium to coarse sand and silty quartz with scattered gravel beds) laid down during the Quarternary period by a river that flowed southeasterly to easterly, is responsible for the high areas of local topography in the city. The Cohansey River eroded the formation, resulting in a narrow river plain flanked by higher ground, sloped steeply on the west side and more gently on the east. The quartz sands found in the Cohansey Formation, purified over the ages by weathering and decay of softer minerals, was critical in development of the county’s glass industry; molding sands, aggregates of sand and clay, were mined from the Bridgeton Formation for the production of cast iron molds.

The Lenni Lenape, the indigenous people of the New Jersey, were long established along the length of the Cohansey River, and in fact gave it its name. Before European contact in the early seventeenth century, the Lenape were numerous throughout the area. Along the Cohansey, they maintained several semipermanent and seasonal villages, with a permanent village located near Bridgeton serving as the cultural center for the southern part of the state.

Known to the English settlers in the late seventeenth century as Cohansey Bridge, the town became unofficially known later in the century as Bridgetown and, in the early nineteenth century, Bridgeton. The early settlement straddled two townships, Deerfield on the east side of the Cohansey River and Hopewell on the west. The township of Bridgeton was set off from Deerfield in 1845, and three years later the township of Cohansey was set off from Hopewell. It was not until 1865 that the townships of Bridgeton and Cohansey were incorporated as the City of Bridgeton with an area of 6.4 square miles.

Cohansey Bridge Edges Ahead

When Cumberland County was formed from the southeastern portion of Salem County in 1748, the hamlet of Cohansey Bridge had only eight to ten houses. The site was initially included in the tenth share of John Fenwick (1618-83), proprietor of West Jersey, and was first settled by Fenwick’s surveyor general, Richard Hancock (ca. 1640-89), who established a sawmill there sometime before 1686. A bridge over the Cohansey was constructed before 1716, but Greenwich, laid out on the river closer to the bay in the 1670s, continued to be the major settlement and established port. Court was first held in Greenwich in 1748 at the direction of the governor, but an election late that year designated Cohansey Bridge as the location for the court and jail. This essentially authorized Cohansey Bridge as the county seat, to the consternation of the inhabitants of Greenwich who, assuming victory, neglected to vote.

Development continued slowly in the eighteenth century, centered on the bridge crossing and mills run on water power supplied by Mill Creek, an east bank tributary of the Cohansey. In the early nineteenth century, the construction of Tumbling Dam, a mile north of the town center, harnessed the water power of the upper reaches of the Cohansey River watershed. About 1814, a fifty-percent share of the water power was purchased by well-capitalized brothers Benjamin (1779-1844) and David (1793-1871) Reeves of Deptford Township, great-grandsons of John Reeves (1674-1748), exclusive operator of the early eighteenth-century ferry between Burlington and Philadelphia. The Reeves brothers were attracted to the site by the abundant water power that enabled them to establish the Cumberland Nail Works, which soon became a major manufacturer of cut nails. Philadelphia nail maker Joseph Whitaker Jr. (1789-1870) joined the Reeves brothers in 1820, and the next year together they purchased the Phoenix Iron Works at Phoenixville, Pennsylvania. The cut-nail operation thrived, shipping nails up and down the East Coast and eventually expanding to include a rolling mill and gas-pipe mill.

The founding of the Cumberland Nail Works marked a turning point for Bridgeton. A petition by leading citizens for a state-chartered bank had been denied in 1815, but the nail company boosted the town’s reputation, and an 1816 petition resulted in the charter of the Cumberland Bank, the only New Jersey bank south of Camden. This stable, conservative institution served Bridgeton for almost two centuries until it lost its identity in the wave of bank mergers of the late twentieth century.

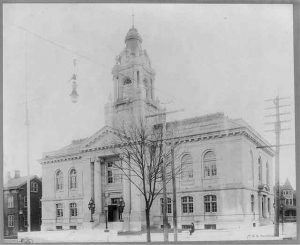

Millville, closer to the geographical center of Cumberland County, grew rapidly in the early nineteenth century, and its residents challenged Bridgeton’s for the location of the county seat in 1837. The c.1760 courthouse was in poor condition and needed to be replaced. The citizens of Millville argued that if there was to be a new building, the county seat should be moved to their town. With four townships on the east side of the county and four on the west, each having two votes, a stalemate prevailed for six years. In 1844, the western townships persuaded the state legislature to form a fifth township, Columbia, on the west side, in the later location of Shiloh, to add an additional two votes in favor of Bridgeton. With ten votes to eight, the west side prevailed, and Bridgeton remained the county seat. The new courthouse was finally built in 1844, and Columbia Township was dissolved the next year.

Industry Grows

As Bridgeton developed, its location in the center of farmland rich in loamy soils made it the processing and transportation center for the agricultural production of western Cumberland County, and the commercial center for the surrounding townships. After the establishment of the nail works, industry within the town grew and diversified, supported by the availability of water power, water transportation, and the nearby quartz and molding sand deposits, essential for the manufacture of glass and cast iron. Glass, iron foundries, and agricultural produce processing, along with clothing manufacturing, developed as major contributors to the town’s economy, with the production of lime, fertilizer, cigars, trunks, soap, shoes, paper, carriages, leather, and ships comprising lesser industries.

A symbiotic relationship fed the food processing and glass industries. Bridgeton’s glass industry began in 1836 with the establishment of Stratton, Buck and Co. Eventually, Bridgeton had twenty glass factories. One of them, Cumberland Glass Manufacturing Company (established 1880), was purchased in 1920 by Owens Bottle Machine Company, which soon became Owens-Illinois and grew into one of the largest glass factories in the country. The glass industry attracted numbers of German glassworkers, the first major influx of immigrants to the area since the seventeenth century.

The major consumer of glass bottles and jars was the food processing industry handling the agricultural output of the surrounding townships. Between 1860 and 1890, twenty-three new canneries began operating, thirteen of them in Bridgeton. Products included beans, asparagus, pumpkin, peaches, pears, cranberries, but above all else, tomatoes. Tomatoes were processed whole and pureed and made into catsup. Tomatoes not processed in Bridgeton were shipped by barge to the Campbell Soup Company in Camden, which had been founded in 1869 by Bridgeton native Joseph A. Campbell (1817-1900).

The industry that perhaps became Bridgeton’s best known was the Ferracute Machine Company, started in 1863 by Oberlin Smith (1840-1926), to make cast-iron fences and church furniture. Early on, the firm began to specialize in can presses for the local food industry, developing a second synergetic relationship between two Bridgeton industries.

River’s Key Role in Transit

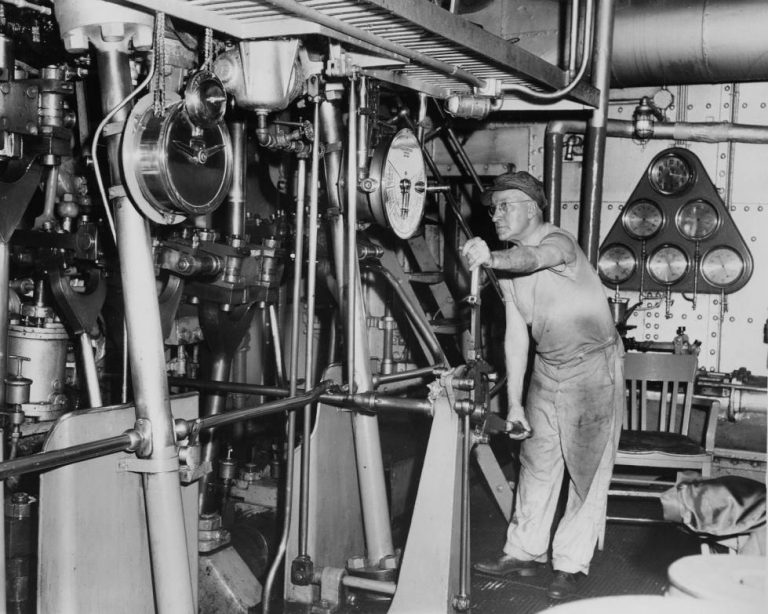

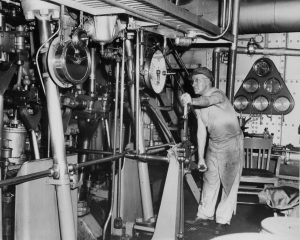

Although Bridgeton was served by two separate railroads, the West Jersey and the NJ Southern, the Cohansey River continued to be its main connection with the rest of the world. By the 1880s, coal and lumber came up the river and, annually, 100,000 kegs of nails, 1.5 million feet of gas pipe, 30,000 tons of glass, 1,000 cords of oak and pine, 100,000 bushels of corn, and three million shaved barrel hoops were shipped out. For passengers, the steamer Artisan made regular semi-weekly trips between Bridgeton and Philadelphia.

The town’s prosperity accrued wealth to the business and industry leaders, many of whom invested in substantial residences designed by Philadelphia architects such as William Strickland (1788-1854), Thomas Ustick Walter (1804-87), Samuel Sloan (1815-84), and Wilson Eyre (1858-1944). Most of the homes of the middle class were vernacular frame double houses, with two residences sharing a party wall; many of these featured a front cross-gable, adding a touch of Gothic Revival style. This significant collection of architectural stock was recognized in 1982 by the listing of the Bridgeton Historic District, comprised of more than two thousand structures, on the National Register of Historic Places.

Bridgeton’s reputation as an educational center grew from several small private schools that opened in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The public school system opened two schools in 1847 and 1848 and thereafter offered free education to all children. The Presbyterians of South Jersey selected Bridgeton for their West Jersey Academy, a boarding school for boys, in 1852. Margaretta Little Sheppard (?-1881) opened Ivy Hall Seminary in 1861; girls from many states attended the boarding school during its fifty-eight years of operation. Bridgeton persuaded the South Jersey Baptist Association to locate its coed South Jersey Institute in the city, where it operated as a boarding school from 1871 until 1907.

By the close of the nineteenth century, wire nails made cut nails obsolete, and Cumberland Nail and Iron struggled throughout the 1890s. In 1899, the Cumberland National Bank, the company’s chief creditor, bought the property at public auction for $70,000. Although Bridgeton had lost a major industry, it gained a park that remained a primary asset. The bank sold the 500-acre property, including the lake, dam, raceway and wooded tract to the city for $35,000 to become the treasured Bridgeton City Park, which, with subsequent additions, grew to encompass about a third of the city.

“Gem O’ Jersey”

The loss of Cumberland Nail and Iron struck a major blow to the town’s confidence in its future, but other industries were thriving and soon grew to fill the company’s place. By the 1920s, the Chamber of Commerce was promoting the town as the “Gem O’ Jersey,” a nickname that persisted for decades as the economy and the population continued to grow until the early 1960s.

After exhibiting at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, the Ferracute Machine Company experienced exponential growth, and by the end of the decade was shipping presses to Japan, Australia, France, Sweden and Bolivia. The firm entered a new segment of the market in 1892 by shipping a coin press to the United States Mint in Philadelphia, and, four years later, successfully bidding for three entire mints to be fabricated, shipped, and set up in China. In the early twentieth century, Ferracute entered the automobile market, and until closing in 1968, Ford Motor Company was its primary client. On an emergency basis during World War II, Ferracute supplied most of the presses required to replace the ammunition left behind at Dunkirk.

A clothing industry began in the nineteenth century with fabric mills and several shirt factories; much of the impetus came from the small clothing factories initiated to supplement farming income by the Russian Jews relocated to Cumberland County following the pogroms of the 1880s. In the twentieth century, the industry grew to include a dyeing and finishing plant, a fabric manufacturer, and six or more factories making dresses, lingerie, and uniforms. Seibel and Stern Clothing Company specialized in children’s clothing, manufacturing a line of high-end dresses for Yves St. Laurent, and bucking a global trend by exporting Little Star frocks to Japan in the late twentieth century.

Tomato processing continued as a major industry throughout the first three quarters of the twentieth century. Philadelphia’s P.J. Ritter Company moved to Bridgeton in 1917 to be closer to its source of tomatoes and operated until 1975; others included E. Pritchard Inc., West Jersey Packing Co., and a Heinz ketchup plant. At the height of the tomato season in August, trucks loaded with baskets of tomatoes waiting their turn at the plants backed up for blocks, and the smell of stewing tomatoes permeated the town.

Italian Immigrants

Food processing required large numbers of seasonal workers. In the early twentieth century, Italian immigrants living in South Philadelphia were contracted for through brokers and transported to South Jersey for the season. Eventually, a sizable number of Italians settled permanently in Bridgeton.

The Germans, Italians, and Jews who came in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries made their own contributions to Bridgeton’s remarkably multicultural population, unusual for a small town in a rural area. The seventeenth-century English settlers in the region coexisted with the indigenous Lenni Lenape, as well as descendants of the Swedes and Dutch who settled in the area in the early part of the century. Settlements of free blacks, the largest known as Gouldtown, existed from around 1700 just east of Bridgeton; they grew with the arrival of escaped slaves from Maryland and Virginia. The descendants of the nineteenth-century Russian Jewish immigrants owned and operated more than one hundred city businesses in the twentieth century in addition to over fifty professional medical, law, and accounting practices. In the mid-twentieth century, nearby Seabrook Farms attracted immigrants from twenty-five different nations, and in particular became home to Japanese Americans resettled from World War II internment camps and to Estonians fleeing the Soviet Union takeover of their country. Though the original Lenni Lenape population was decimated by disease in the seventeenth century and mass migration to the west in the eighteenth, remnants of the tribe remained in the area and retained representation by the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape, a tribal confederation of the Nanticoke of the Delmarva Peninsula and South Jersey’s Lenape, with headquarters in Bridgeton.

The city did not escape racial friction and prejudice, especially through the presence of an active Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. Although schools were integrated, at least after 1881, de facto segregation existed, such as the relegation of blacks to a movie theater balcony, and the distribution of jobs in the Owens Illinois glass plant according to race and gender. Racial tensions culminated in violent protests in 1971, when fights broke out between white and black students at Bridgeton High School; in March and again in October the fights expanded into the streets, where rioters broke windows, beat bystanders, and ransacked stores. The city was put under a state of emergency, with a dusk-to-dawn curfew. In December, over two hundred students held a sit-in, demanding removal of police from the school, implementation of a black history program, and a racially mixed school board; following the sit-in, black and white students linked arms for a peaceful march through the downtown, marking a defusing of the tensions.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s Bridgeton’s industries shut down one by one as manufacturing left the Northeast. Owens-Illinois closed in 1984 when the glass container industry in the northeastern United States declined as demand shifted from glass to plastic, eliminating about three thousand jobs. As the tax base dwindled, the poverty rate climbed, eventually reaching 33 percent in the twenty-first century and resulting in a high crime rate.

Twenty-First Century Population Rise

Bridgeton’s population reached a peak of about twenty thousand in 1960, then declined slightly over the next thirty years. An influx of immigrants from Latin America taking work in agriculture and horticulture reversed the trend, and by 2010 the population had reached an all-time high of twenty-five thousand. By 2017, the overall population was approximately one-third African American, one-third Caucasian, and one-third Hispanic.

The influx of Hispanic residents began to transform the economy and culture of the city. Most of the newcomers came from the Mexican state of Oaxaca, giving Bridgeton one of the highest concentrations of Zapotec speakers in the country. Bridgeton became the residential center for Hispanic agricultural workers, not just for western Cumberland County but for the region, with some laborers commuting to neighboring counties up to an hour away. As storefronts began to empty, many were filled by Hispanic groceries, restaurants, and dress shops. The town began celebrating Cinco de Mayo along with the Fourth of July and the Cohansey Riverfest.

The nonprofit Center for Historic American Building Arts (CHABA) strove to integrate the Hispanic population into the community by teaching restoration skills to the new homeowners in the historic district and providing a sense of shared place by apprising them of Bridgeton’s agricultural and industrial history. Bridgeton’s historic preservation guidelines were translated into Spanish, as the latest wave of immigrants populated the Victorian housing stock and revitalized the neighborhoods. The commissioning of two works by Philadelphia’s Mexican-American muralist Cesar Viveros Herrera (b. 1968) further melded Bridgeton’s history with its present. In 2017 the City Council instituted a municipal ID program, the first in South Jersey, to assist undocumented residents in opening bank accounts, accessing health care, and participating in city activities.

Development in the twenty-first century was primarily publicly funded. Building on the area’s agricultural and food processing base, in 2008 Rutgers University opened a Food Innovation Center, providing space and expertise for startup food manufacturers and over the next ten years aided more than one hundred new businesses. The Cumberland County Improvement Authority broke ground in 2017 for a $9.2 million Food Specialization Center to help the start-up companies take the next step toward full autonomy. Cumberland County College opened STEAMworks, South Jersey’s first makerspace, in 2015, making available to the public a 3D printer, laser cutter, computer lab with CAD software, a fully equipped recording studio, electronics, and standard power tools. As it had many times in the past centuries, twenty-first-century Bridgeton strove to evolve into a new version of the “Gem O’ Jersey.”

Penelope S. Watson, AIA, is a principal at Watson & Henry Associates, where she has worked as preservation architect for over thirty years. She has an undergraduate degree from Mt. Holyoke College, a professional degree from the Boston Architectural College, and a master’s degree in Preservation Studies from Boston University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2018, Rutgers University