Murals

Essay

Murals in the Greater Philadelphia region, like those in the United States at large, belong to an extraordinarily diverse set of histories and genealogies, from indigenous rock carving to decorations for private houses to paintings in public buildings and community initiatives. Philadelphia-area murals have spanned this diverse heritage, including three particularly important mural movements: Beaux-Arts muralism, which flourished from around 1876 to the mid-1920s; modern murals of the New Deal era (c. 1930-43); and the community mural movement that began in the 1970s.

The word “mural,” from the Latin mur for “wall,” seems to have first emerged in reference to painting in the mid-nineteenth century. Yet the practice of decorating walls and other surrounding structures well predates the term. Petroglyphs discovered near the Susquehanna River in Lancaster County provide striking visual testimony to Algonquin-speaking cultures in the region, with examples dating as far back as 1000 AD. In colonial and early national Philadelphia, painted wall panels—used in doors, over mantelpieces, and as fireboards to cover the hearth—decorated residential interiors, often depicting landscapes or utilizing floral motifs, as in a c. 1761 overmantel from Lancaster County. In the nineteenth century, wall painting became increasingly associated with public buildings. According to Francis V. O’Connor, the earliest public mural in Philadelphia was likely a now-lost fresco cycle in the dome of William Strickland’s Philadelphia Exchange, painted c. 1834-35, that depicted allegories of Commerce, Wealth, and Liberty. Other examples of nineteenth-century wall painting were more closely allied with the fields of architecture and design. George Herzog (1851-1920), for example, completed complex decorative schemes for Philadelphia buildings, combining painting and architectural ornament. His interiors for Philadelphia City Hall and the Philadelphia Masonic Temple feature ornament and symbols from Egyptian, Renaissance, and other historical styles.

Beaux-Arts Muralism, 1876-1925

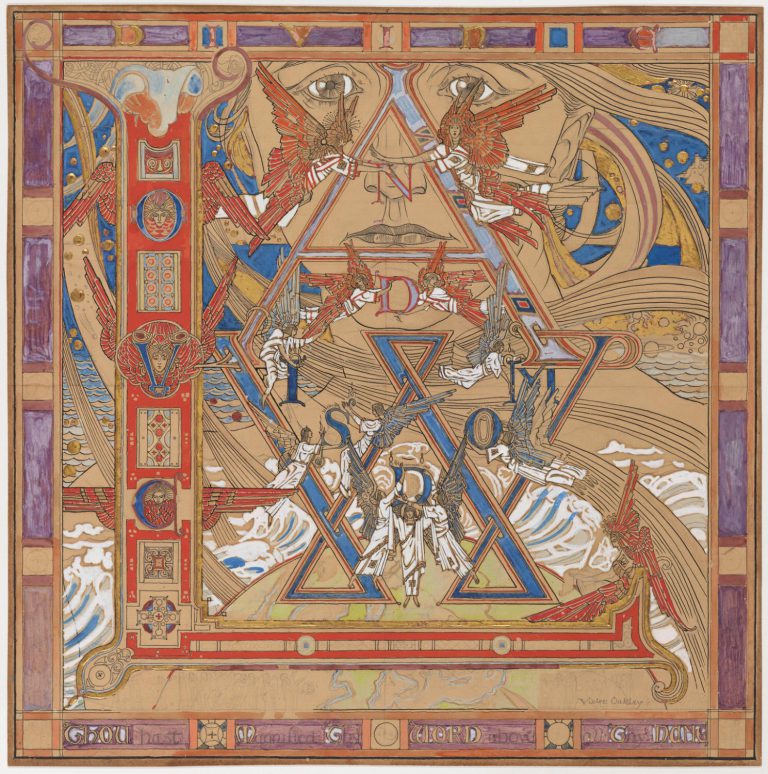

Around the nation’s centennial in 1876, a new and more self-conscious mural movement arose in the United States, one whose style and iconography dominated mural painting for the next five decades. Called Beaux-Arts or American Renaissance muralism, this movement sought to create a public, monumental art that would reflect the nation’s values. Favoring allegory, classical references, and grand historical themes, Beaux-Arts muralists decorated countless statehouses, courthouses, and churches across the country. Painter Violet Oakley (1874-1961) left her particular Beaux-Arts vision—socially oriented, pacifist, and proto-feminist—in several murals in greater Philadelphia. Oakley was the first woman to receive a mural commission for a public building in the United States when she began her cycle at the Pennsylvania State Capitol in Harrisburg in 1902; she would return to the Capitol a decade later to complete several other murals on jurisprudence and the history of nations. Oakley also created decorative programs for private homes and churches, including for the Charlton Yarnall mansion in Philadelphia (1910-11; lunettes acquired by the Woodmere Art Museum) and the late project Great Women of the Bible for the First Presbyterian Church in Germantown (1945-49), painted when Oakley was in her 70s. Other notable murals from the Beaux-Arts era include a cycle by Edwin Blashfield (1848-1936) for the Church of the Saviour in Philadelphia (1906), a mural on the history of coinage by William Brantley Van Ingen (1858-1955) and Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933) for the Philadelphia Mint (1901), and the Trenton City Hall’s Steel and Ceramics Industries (1911) by Everett Shinn (1876-1953), which, in its realist style and scenes of labor, points ahead to themes central to the New Deal murals of the 1930s.

Although Beaux-Arts muralism is most closely associated with civic allegories for public institutions, painters from the period also frequently pursued subjects that were more frankly personal and pleasurable in nature. The cycle by Howard Pyle (1853-1911) for his house in Wilmington, Delaware (1903-07; acquired by the Delaware Museum of Art); the cloisonné stained-glass panels by John La Farge (1835-1910) for the Edward W. Bok house in Merion, Pennsylvania (1907; acquired by the Fleisher Art Memorial, Philadelphia); and the collaboration between Frederick Maxfield Parrish (1870-1960) and Louis Comfort Tiffany for the glass mosaic Dream Garden (1914-15; The Curtis lobby, Philadelphia) present variations of a more romantic, pastoral sensibility.

Modern Muralism and the New Deal

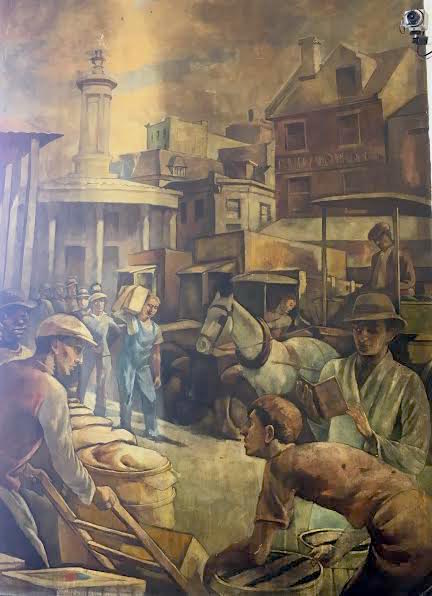

Between 1934 and 1943, hundreds of murals were installed across greater Philadelphia under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project (WPA-FAP), the Treasury Department’s Section of Fine Arts, and other government programs. Unlike Beaux-Arts muralism, these murals favored realism and daily life over classicism and allegory, and they tended to focus on common people and workers rather than heroes and founders. Many were inspired by the modern mural movement begun in Mexico in the 1920s. Murals such as Progress and Industry (1935) and Rural Delivery (1937) by Charles W. Ward (1900-62) for the Trenton post office; The Family—Industry and Agriculture (1939) by Harry Sternberg (1904-2001) for the post office in Ambler, Pennsylvania; and Streets of Philadelphia by Walter Gardner (1902-96) at the Spring Garden post office (1937) exemplify the period’s interest in populist types, American roots, and a “usable past.” Muralists working in this modern, New Deal-era style were also supported by private patrons. Aaron Douglas (1899-1979), for example, continued his exploration of African American and African diaspora history—first established in public murals in New York, Tennessee, and Texas—in Haitian Mural (1942), painted for the private home of W.W. Goens in Wilmington, Delaware. Spreading out above the home’s fireplace, the mural uses Douglas’s characteristic silhouettes to show Haitians striding through a landscape of mountains and forest.

Other mural currents, 1930s-1960s

Other forms of wall painting continued during the 1930s and in the ensuing decades. Art Deco designers utilized wall painting for a host of 1930s structures in Philadelphia, including the Board of Education Administration Building (1929-31), the N.W. Ayer Building (1928), and the WCAU Building (1928). European modernists were also experimenting with the mural in these years, and some examples can be found in greater Philadelphia. The mural by Henri Matisse (1869-1954) for the Barnes Foundation (1932-3), commissioned by Albert C. Barnes himself, fills the lunettes of the foundation’s building, continuing a long tradition of French abstraction and decorative wall painting. Family of Man (1961), a pair of cast concrete walls in low relief by muralist and sculptor Costantino Nivola (1911-88), sits outside the Van Pelt Library, University of Pennsylvania, showing abstracted shapes suggestive of the human body. American artist Ellsworth Kelly (1923-2016) also explored the intersection of two and three dimensions in his Sculpture for a Large Wall (1956-7), a sixty-five-foot-long abstract surface of aluminum rods and tilted monochrome panels. Originally installed in the Philadelphia Transportation Building, the mural was removed in 1995 and eventually ended up at the Museum of Modern Art in New York; it returned to Philadelphia for a brief showing in 2013 at the Barnes Foundation.

The Community Mural Movement in Philadelphia

Beginning in the 1970s, artists and activists in Philadelphia turned to a new form of mural painting, one sited in urban spaces, grounded in community participation, and taking inspiration from contemporary street art. Don Kaiser (b. 1945) and Clarence Wood (b. 1943), working through the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Department of Urban Outreach, spearheaded the creation of over 150 murals throughout the city from 1970 through the early 1980s, often in close collaboration with local citizens. In 1986, artist Lily Yeh (b. 1941) began Ile-Ife Park: The Village of Arts and Humanities in North Philadelphia with community residents. A park filled with murals, mosaic sculptures, and plantings, it has served as a site of both public art and community engagement. With its aesthetic of mosaics and found objects, Ile-Ife resonates with other public art in the city, like that of Isaiah Zagar (b. 1939). Zagar’s public mosaics, dating back to the 1960s, can be found on walls throughout the city, and his immersive installation Philadelphia’s Magic Gardens, begun in the 1990s, is now a museum.

Around the 1990s, Philadelphia’s community mural movements began to attain national and international recognition. Organizations like the Brandywine Workshop (founded 1972), Taller Puertorriqueño (founded 1974), and the Mural Arts Program (founded in 1984 as the Philadelphia Anti-Graffiti Network) played a major role in the ongoing commissioning and painting of these murals, including iconic examples like We the Youth (1987) by Keith Haring (1958-90) and Jackie Robinson (1997) by David McShane (b. 1965). The growth of institutions dedicated to mural painting is part of a larger trend in American cities, where many mural movements, once informal and relatively unknown, have achieved a new level of status and professionalism. While this has allowed for greater visibility and funding for murals, it has also opened community muralism up to criticism. Some have noted the dilution of earlier, more radical goals, while others have criticized the movement’s role in social control (through, for example, anti-graffiti measures), urban renewal, and gentrification.

The Mural Arts Program remains one of the most well-known and most prolific mural organizations in the country. Founded by artist Jane Golden (b. 1953), the program has completed over thirty-eight hundred works since its founding and made the styles of muralists like Michael Webb (b. 1947) and Meg Saligman (b. 1965) common sights across Philadelphia’s outdoor walls. Their murals often reflect on the city’s past and present, as in Webb’s Tribute to Julian Abele (2011), which celebrates the first African American graduate of the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Architecture, or Saligman’s Common Threads (1998), a vast, eight-story painting juxtaposing Philadelphia high school students and ancient figurines. Local politics and folk traditions are rendered in works like Frank Rizzo (1995) by Diane Keller (b. 1948) and Welcome to Mummer Land (1999) by Robert Bullock (b. 1953). Committed to the idea that “art ignites change,” Mural Arts has branched out into initiatives geared at schoolchildren, prison inmates, and victims of violence. Other projects have encouraged transnational collaboration, as in Aqui y Alla (2007), a mural by Philadelphia artist Michelle Angela Ortiz (b. 1978) and Mexican artist groups Colectivo REZIZTE and Colectivo Madroño, and investigated the nature of contemporary muralism, as in its muraLAB program.

These contemporary murals continued a long tradition of mural painting in and around Philadelphia. Like their predecessors, they constituted part of the built environment and its history. In addition to being fascinating works of art in their own right, the murals of greater Philadelphia have chronicled society’s changing notions of public space and the role of art in the urban landscape.

Emily S. Warner received her B.A. in Art History from the University of Chicago (2006) and her M.A. in the History of Art from the University of Pennsylvania (2012), where she is a doctoral candidate. Her research interests include topics in both nineteenth- and twentieth-century art history and visual culture. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- The woman behind the many murals in Pennsylvania's State Capitol (WHYY, June 8, 2011)

- Young Mexican immigrants bridge 'here' and 'there' with mural (WHYY, September 17, 2012)

- New autumn-inspired mural will replace the one lost in Bella Vista (WHYY, June 4, 2012)

- Shepard Fairey mural overlooks Fishtown [photos] (WHYY, August 8, 2014)

- Mural Arts Program investigates destruction of Dox Thrash tribute (WHYY, November 29, 2012)

- Mt. Airy mural dedicated to 'those who see it' (WHYY, November 11, 2013)

- Rare Keith Haring collaborative mural repaired and relished in Point Breeze (WHYY, October 30, 2013)

- 30 years of Mural Arts: looking 'beyond the paint' [photos] (WHYY, November 19, 2013)

- Philly's Mural Arts reaches out to prisoners as it shapes installation on criminal justice (WHYY, November 30, 2016)

- For the first time in 75 years, Howard Pyle's first murals together again at Delaware Art Museum (WHYY, April 17, 2017)

- New mural to honor Philly native Ed Bradley of '60 Minutes' (WHYY, May 2, 2017)

- At Philly archive's new home, redlining mural charts dark chapter of city history (WHYY, December 7, 2018)

- How Philly became the 'Mural Capital of the World' (BillyPenn/WHYY, November 24, 2024)

Links

- Building and Preserving a House of Wisdom (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Pending Destruction of Zagar Mural Spurs Community into Action (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- PhilaPlace: Taller Puertorriqueño (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program

- Violet Oakley Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)