Commuter Trains

By John Hepp | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Commuter trains have helped to shape and define Philadelphia and its region since their introduction in 1832. The trains influenced suburban development and shaped Center City. For most of this period, the trains charged higher fares than other forms of public transit and remained a largely middle-class means of transport. Commuter trains connected middle-class homes in the city’s neighborhoods and suburbs with the offices, stores, and entertainment of Center City and, according to historian Jack Simmons, allowed for “the liberation of [middle-class] women” in the late-nineteenth century. By the twenty-first century, commuter trains offered a “green alternative” to the crowded highways and automobile-oriented culture of the United States.

The region’s first commuter rail line was the Philadelphia, Germantown & Norristown Railroad (the PGN), which began operation in 1832. This line, like Britain’s London & Greenwich Railway (opened in 1836), was designed from the outset to rely upon local traffic. Prior to the Civil War, in general, railways tended to be either local carriers (like the PGN), which carried extensive commuter traffic, or “trunk line” railroads, like the Philadelphia & Columbia (later the Pennsylvania Railroad), which tended to focus on long-distance freight and passenger traffic and had very few local trains. One notable exception to this early dichotomy was the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad that both linked its namesake cities as a trunk carrier in 1838 and began actively developing commuter traffic from the 1850s.

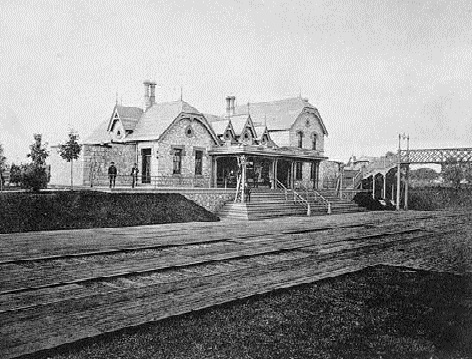

Better Stations

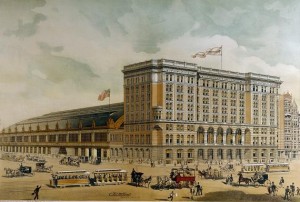

In the 1870s and 1880s, a variety of factors ranging from increased railway consolidation and greater competition among the surviving companies to new and better central passenger stations in Philadelphia, allowed for the region’s three railroad systems (the Pennsylvania, Philadelphia & Reading and Baltimore & Ohio) to build or assemble extensive commuter networks centered on Philadelphia and Camden. In fact, competing lines were built to Chester, Norristown, and Chestnut Hill, as the railroads’ only competition for travel beyond two miles or so were other railroads. The final decades of the nineteenth century were truly the halcyon days of commuter rail service in the region with a large variety of lines linking the city to its hinterland. In addition to the lines focused on Center City and Camden, during this period there were smaller commuter nodes in North and Northeast Philadelphia.

By about 1890, however, the commuter railroads had their first real competition from the electric streetcars (especially when suburban trolleys were allied with urban subway and elevated trains). The Pennsylvania Railroad experimented with electrifying its Mount Holly branch in New Jersey between 1895 and 1901 using electric streetcar technology, but, like most other steam railroad attempts at using trolley technology on existing lines, this was a “one off” trial. More effectively, the railroads focused on developing greater passenger traffic in the five-mile or more range and often conceded the short distance trips to the trolleys. This strategy worked well and commuter rail traffic continued to be robust on most lines in the region.

Mainline electrification, developed in the first decade of the twentieth century, became the technological change that largely defined commuter rail service for the Philadelphia region. Initially, the Pennsylvania Railroad pioneered heavy-rail electrification in southern New Jersey not because of local needs but as a way to experiment with the technology required for its railroad tunnel to Manhattan under the Hudson River. In 1906, the railroad electrified its underused secondary line between Camden and Atlantic City via Newfield using third-rail technology for both local and through trains. In the next decade, capacity issues at the busy Broad Street Station in Philadelphia caused the Pennsylvania to electrify its lines to Paoli (in 1915) and Chestnut Hill (in 1918), using what would become the region’s standard: overhead catenary. Based on the success of these lines, both the Pennsylvania and the Reading electrified other lines in the region through 1933.

Great Depression’s Impact

Although the contraction of commuter rail services in the region began in reaction to the trolleys in the 1890s, much of the network remained intact until the Great Depression. Starting in the 1930s, most lines that were not electrified cut service. This retrenchment, though delayed by World War II, continued in the 1950s and 1960s as the now struggling railroads sought to slash costs. In 1949, the Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines route to Millville, a remnant of the 1906 Atlantic City electrification, was converted back to steam operation (and eventually would lose all service by 1971). By the mid-1960s, the only non-electrified commuter services operated in the Philadelphia region were those of the Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines, a few Pennsylvania Railroad branches in southern New Jersey, and the Newtown line of the Reading in Bucks County.

In reaction to these service cutbacks, local and state governments became involved in commuter rail traffic starting in the late 1950s. In 1960, the City of Philadelphia began subsidizing service and purchasing equipment for use on lines in the city to Chestnut Hill and Manayunk. In 1966, Philadelphia paid for the electrification of the Reading’s Newtown line within the city limits to Fox Chase. The South Eastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) began in 1965 to coordinate and fund all local passenger services in the area. SEPTA bought new equipment and built the Center City Commuter Connection, which opened in 1984, linking the former Pennsylvania and Reading systems as a truly regional system. Similar changes happened in New Jersey, but, by the time they did, the only train services remaining in southern New Jersey were the lines to the shore with few commuters.

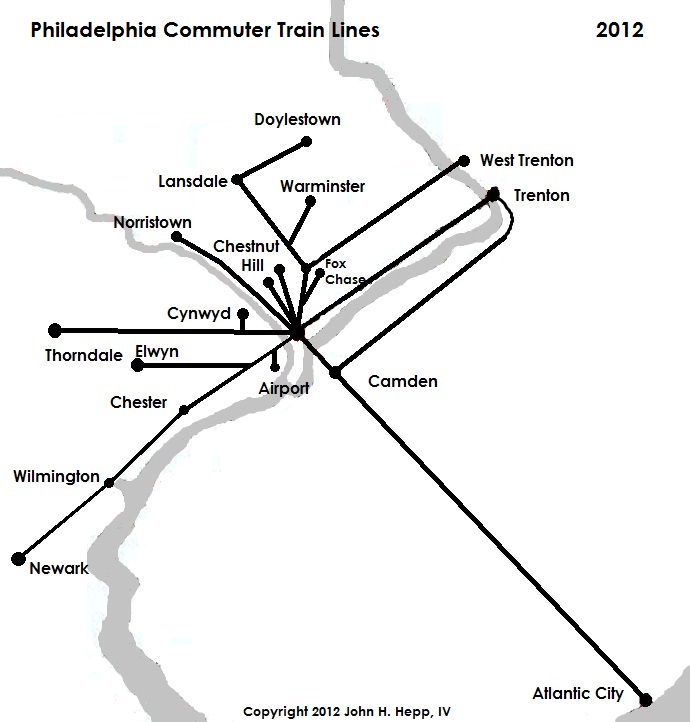

Since the 1970s, government agencies have been responsible for the development of commuter rail service in the Philadelphia region. In 1976, all of the railroads in the region that still had passenger service were merged into the Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail). In 1983, Conrail ceased running commuter trains and SEPTA took over their direct operation in its region. The transition was not an easy one and, after a strike and a period of closure, it took years for SEPTA to recover lost riders. SEPTA has expanded service on longer distance routes and opened more park- and-ride stations in the outer suburbs, at the cost of more restricted and expensive short-distance service. In New Jersey, the rail route to Atlantic City from Philadelphia (closed in 1982) reopened in 1989, with Amtrak initially providing long distance service and NJ Transit commuter trains. Since 1995, all service has been operated by NJ Transit. In 2004, NJ Transit opened the River Line between Trenton and Camden. In 2012, DART First State, Delaware’s transit provider purchased its first railway cars ever, for operation with SEPTA coaches on the Wilmington-Newark line.

Commuter trains in the twenty-first century confronted such major dilemmas as uncertain funding and the problem of how to follow jobs to the suburbs when the rail routes were largely fixed. The three commuter train operators and funders in the region — SEPTA, New Jersey Transit, and DART First State–faced the challenge of adapting to these changes as the region’s transportation needs continued to evolve, as their predecessors had done for the last one hundred and eighty years.

John Hepp is associate professor of history at Wilkes University in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, and he teaches American urban and cultural history with an emphasis on the period 1800 to 1940. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2012, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- SEPTA taps hard-won $2.4B transportation funding for first project (WHYY, January 24, 2014)

- Proposed Glassboro-Camden commuter train line might have to skip Wenonah (WHYY, March, 25, 2014)

- Ben Franklin Bridge track work means summer of discontent for PATCO riders (WHYY, May 15, 2014)

- Inside Amtrak's new fleet of high-tech train engines (WHYY, May 17, 2014)

- PATCO construction to linger through summer (WHYY, May 30, 2014)

- SEPTA running weekend service this summer on El, Broad Street Line (WHYY, June 3, 2014)

- Broad Street, Market Frankford subway service for night owls (WHYY, June 13, 2014)

- No deal: SEPTA Regional Rail workers announce strike (WHYY, June 14, 2014)

- Obama intervenes in SEPTA strike: Service restored by Sunday Morning (WHYY, June 14, 2014)