Armstrong Association of Philadelphia

Essay

The Armstrong Association of Philadelphia was a social-service organization established early in the twentieth century to assess and address the needs of the African American community. Through its efforts to improve education, housing, and health, the organization addressed social and economic issues facing African Americans.

Founded in 1908, the association formed as a branch of the New York-based organization named for Civil War General Samuel C. Armstrong (1839-93), who led the 8th United States Colored Troops. After the war, in 1868, Armstrong founded the Hampton Institute in Virginia as an industrial school for students of color and to produce African American teachers. The Armstrong Association raised funds for the Hampton Institute and for Tuskegee University in Alabama, founded in 1881 by one of Hampton Institute’s most famous graduates, Booker T. Washington (1856-1915).

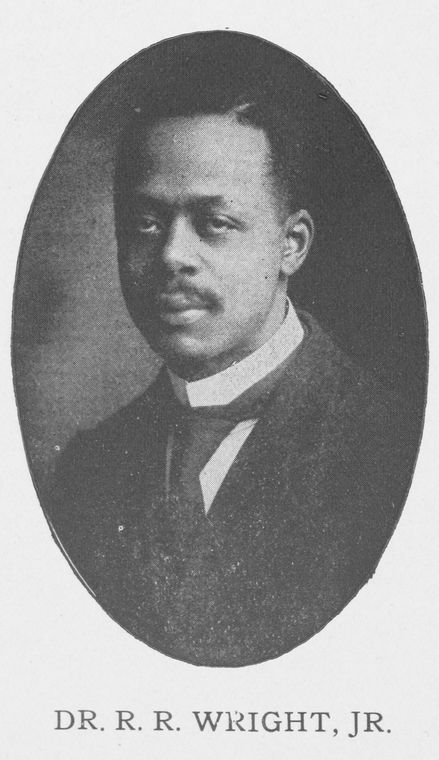

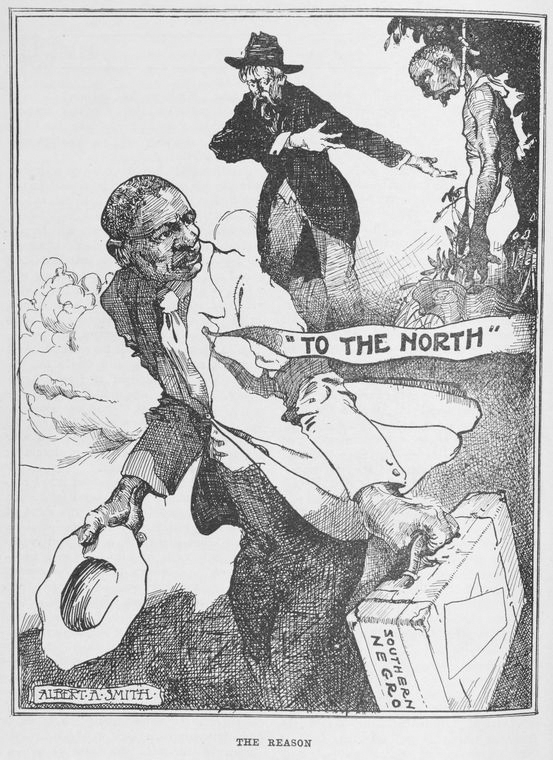

Philadelphia’s Armstrong Association began after Hampton educator John Thompson Emlen (1878-1955), who was part of the organization in New York, came to Philadelphia intent on bettering the conditions for African Americans. He believed that a branch of the Armstrong Association could supplement existing social institutions to address the needs of a steadily growing population of African Americans migrating from the South (a trend later termed the Great Migration). After a meeting between Emlen and Richard R. Wright Jr. (1878-1967), a doctoral student at the University of Pennsylvania, the Philadelphia branch began its work.

Originally, the Armstrong Association consisted primarily of wealthy white philanthropists, but Emlen believed that an interracial board was key to the organization’s success. Each position on the board had two appointees: a white person as well as an African American. Emlen served as the organization’s secretary, and Wright acted as field secretary.

Joining forces with the Philadelphia Housing Association and the Traveler’s Aid Society, the Armstrong Association studied living conditions and overcrowding during the Great Migration as African Americans flocked to northern cities seeking economic opportunities and better social conditions. In 1900, the African American population of Philadelphia was 63,000. By 1910, it had grown to 84,459 and within another ten years it surpassed 134,000. In addition to a housing shortage, new arrivals found it difficult to find employment, especially in their previous fields. Wright, who earned his doctorate in sociology, noted in his dissertation that many African American migrants to Philadelphia were skilled laborers, but they often faced discrimination from employers and had to take jobs outside their skill sets. In response, the Armstrong Association developed initiatives such as an annual job fair, reports to monitor working conditions of African Americans, and representation in cases of workplace disputes.

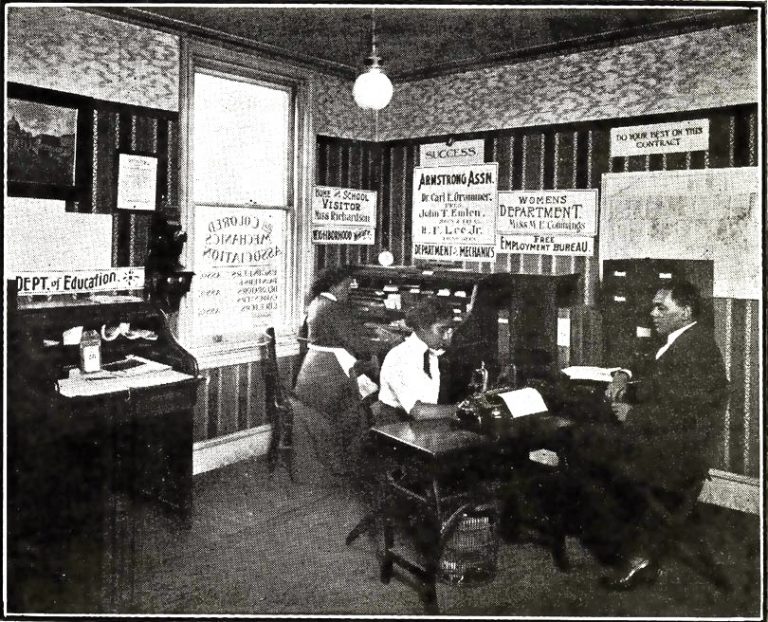

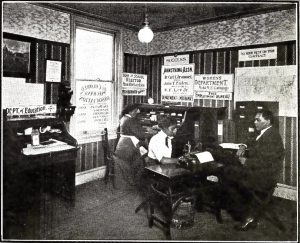

Using the Thomas Durham Public School at Sixteenth and Lombard Streets as a case study, the organization created a learning and social center to help African Americans with job placement and skill assessments. The school, named for a former administrator in the Philadelphia School District, was established in 1910 and served a predominantly African American student body. In a study, the Armstrong Association found that only 53 of the 163 students of working age were able to secure work. Those who did found occupations that required very little skill and no room for advancement and provided a poor living wage. The Armstrong Association determined that providing students with better vocational training would prepare them to enter the workforce.

The association also provided job placement services for African American migrants, documented by oral history interviews conducted in the 1980s by historian Charles Hardy. The association’s industrial secretary, Alexander L. Manly (1866-1944), who joined the organization in 1913, secured more than $35,000 in contracts for African Americans within his first eight months in the position. Despite racial discrimination, the organization succeeded in aiding many newcomers searching for employment.

Emlen spent the remainder of his career in public service with the organization, while Wright left the group in 1909 because he favored self-help over the Armstrong Association’s emphasis on philanthropy. Wright later became a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. The Armstrong Association of Philadelphia went on to affiliate with the National Urban League in a merger that created the Urban League of Philadelphia in 1957. Through its work, the Armstrong Association of Philadelphia helped a generation of African Americans who migrated from the South find housing and employment in their new city.

Sharece Blakney is a graduate student in American History at Rutgers-Camden. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Goin' North: Stories From the First Great Migration to Philadelphia

- In Motion: The African American Migration Experience

- The African American Museum in Philadelphia

- Civil Rights in a Northern City: Philadelphia (Temple University)

- Urban League of Philadelphia