Art Deco

Essay

Like other major American cities in the 1920s and 1930s, Philadelphia was an epicenter for the exuberant strain of architecture and design activity that came to be known as Art Deco. Fueled by the area’s economic importance and increasingly urban character after the First World War, designers, corporations, and manufacturers all engaged in a broad search for a distinctly American form of design appropriate for the modern age.

Art Deco is generally considered to have its roots in the French moderne style that arose in the early twentieth century. Although the style contained great variety, moderne furniture, decorative objects, and interiors were generally characterized by restrained, simple forms (some inspired by classical or otherwise traditional precedents) rendered with luxurious materials like exotic wood veneers, precious metals, or sharkskin. The 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris celebrated this approach, showcasing the most modern of Europe’s decorative arts. While the United States did not participate in the exhibition, the event was heavily covered in the press and had a palpable impact on the design professions. American Art Deco was also influenced by avant-garde European art styles, particularly Cubism, that attempted to capture the rapid technological, economic, and societal changes of the interwar period.

The larger umbrella of “Art Deco” (a term applied retroactively by later scholars) included a diversity of simultaneous and even contradictory stylistic approaches, from luxurious upscale goods and interiors inspired by the French moderne to the more populist, mass-market products of the machine age that arose after the onset of the Great Depression. But it was precisely this heterogeneity that made Art Deco such an intriguing and widespread vein of design, and the creativity of interwar architects, designers, and manufacturers would leave a lasting legacy on the built environment of Greater Philadelphia.

Philadelphia architect William L. Price (1861–1916) and his firm Price & McLanahan, although best-known for their involvement in the Arts and Crafts movement, signaled some of the directions later Art Deco architecture would take with their 1916 expansion of the Traymore Hotel in Atlantic City, New Jersey, into a massive resort complex with an innovative concrete structural system. The hotel combined bold architectural massing, radically modern construction techniques, and a rich decorative program—elements that would come into play in many Art Deco buildings of the 1920s and 1930s.

Iconic Skyscrapers

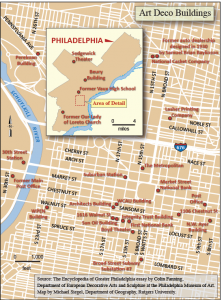

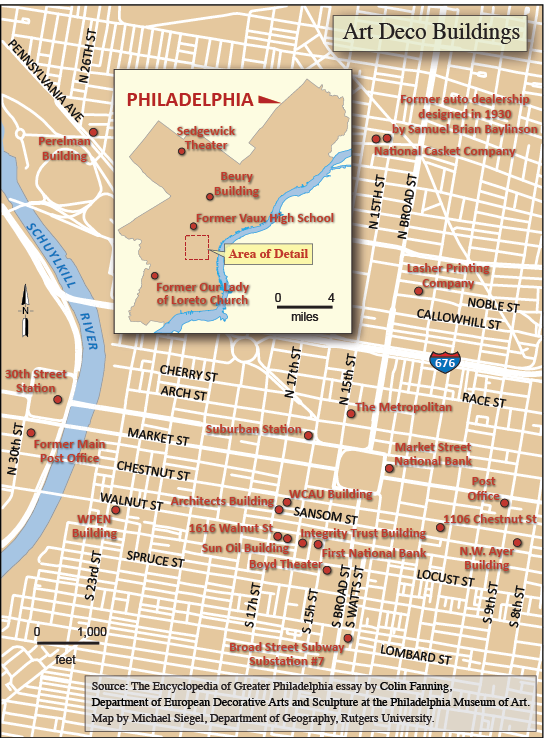

One of the building types most closely associated with Art Deco was the skyscraper, a triumphant icon of construction technology, American financial might, and the growing cultural power of large cities. One of the earliest Art Deco skyscrapers in Philadelphia proper was the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) Armed Forces Building (today a luxury apartment building, The Metropolitan) on Fifteenth Street near Arch Street in Center City. Completed in 1928 and designed by the New York–based architect Louis Jallade (1876–1957), the tower featured distinct zigzag banding on its upper stories and a colorful cornice of modular geometric terra cotta decoration. Other notable examples of similarly adorned high-rise Art Deco buildings in Philadelphia included Ritter and Shay’s Market Street National Bank (1319 Market Street; built 1931); Tilden, Register & Pepper’s Sun Oil Building (1608-1610 Walnut Street; built 1928); and the Architects Building at 121 S. Seventeenth Street, completed around 1930. Designed by the prominent French-born, Philadelphia-based architect Paul Philippe Cret (1876–1945), who in this later phase of his career moved sharply away from the Beaux-Arts style toward the moderne, the Architects Building housed numerous architectural offices and attested to the central role of the profession in shaping the city’s modern landscape.

Large corporate or institutional clients turned to Art Deco in an attempt to project an image of modernity as well as an optimism in technological and cultural progress. Philadelphia’s WCAU Building (1931) at 1622 Chestnut Street, the first radio-station headquarters in the country to be purpose-built, also expressed the excitement of new material treatments for architecture. Architects Gabriel Roth (1893–1960) and Harry Sternfeld (1888–1976) created an unusual façade that incorporated crushed glass and decorative metalwork in brass, copper, and stainless steel. The Fidelity Mutual Life Insurance headquarters by the firm of Zantzinger, Borie & Medary (completed 1928; today the Perelman Building of the Philadelphia Museum of Art), meanwhile, was a lower-rise building whose decoration took inspiration from classical forms, highlighting how interwar designers reworked and simplified historical styles to signal a modern spirit.

A grand example of a civic building in the Art Deco mode was the United States Post Office (built 1931–35 by the firms Rankin & Kellogg and Tilden, Register & Pepper in partnership) at the intersection of Market and Thirtieth Streets. The limestone-clad building was organized much like a factory to accelerate the mail-distribution process, and its rich but selectively applied decoration visually reinforced the ethos of speed and efficiency.

In addition to these large, expensive corporate and civic buildings, a concurrent thread of Art Deco was manifest in smaller-scale, more populist kinds of architecture like theaters, storefronts, and eateries. Business owners who wanted to mark their establishments as up-to-date and stylish deployed moderne decoration and new materials. Architect William Harold Lee (1884–1971) designed several theaters around greater Philadelphia, while Ralph Bencker (1883–1961) designed many of the region’s numerous Horn and Hardart’s automat cafeterias. And despite Art Deco’s close association with big-city life, it was not solely an urban phenomenon: The main streets in smaller communities in surrounding parts of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware often sprouted “modernistic” buildings as businesses competed for customers’ attention.

Transportation Makeover

American notions of progress were often tethered to transportation as a particular arena of invention. Amid the rise of widespread car ownership, the gradually increasing accessibility of air travel, and the luxurious experience connoted by the great ocean liners—all modes of travel that frequently carried their own Art Deco styling—railways in particular felt a need to project an image of modernity to remain competitive. Railway station architecture was one prominent vehicle for such design activity. The exterior entrances of Suburban Station (built 1930) in Center City Philadelphia appealed to the spirit of the age through exuberant decorative metalwork. Although Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station (built 1929–34 by Chicago firm Graham, Anderson, Probst & White) sported an exterior in the Beaux Arts tradition, its grand interiors epitomized the simplified moderne approach to classicism.

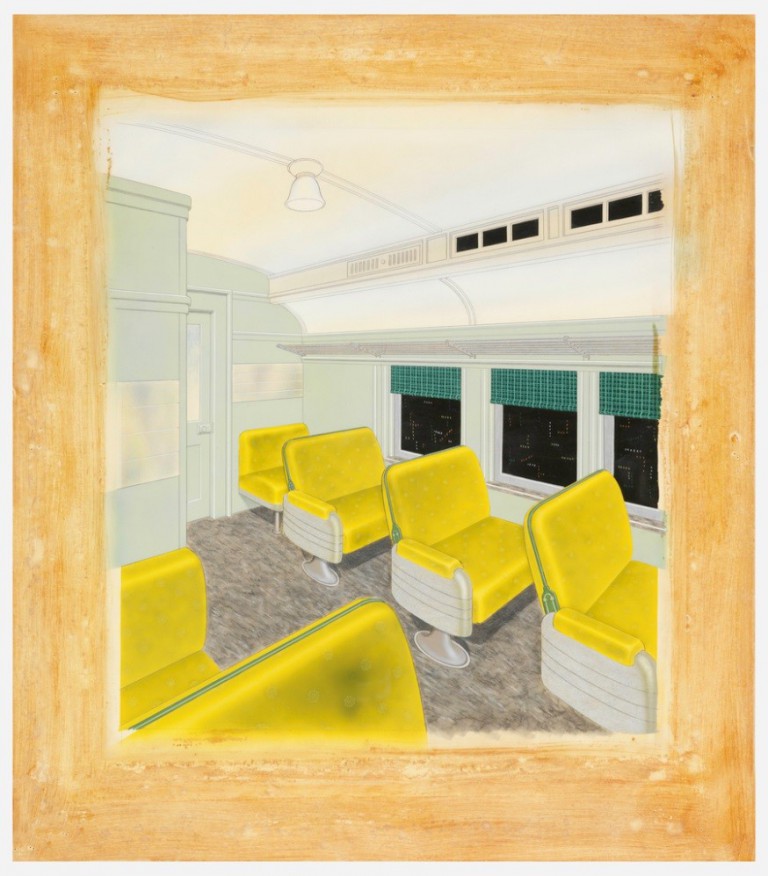

In addition to self-consciously modern station architecture, the Pennsylvania Railroad experimented with the design of locomotives and rolling stock to reinforce their connotations of speed and modernity. Locomotives like the iconic S1 Class and the interiors of passenger cars designed by the prominent industrial designer Raymond Loewy (1893–1986) typified the vogue for “streamlining” that emerged with a force in the 1930s. Characterized by smooth contours, rounded forms, and a general horizontality often heightened by bands of “speed lines” (whether the object was meant to be mobile or not), streamlining was one material manifestation of a widely held sense that the modern world was running at a faster pace than in previous periods.

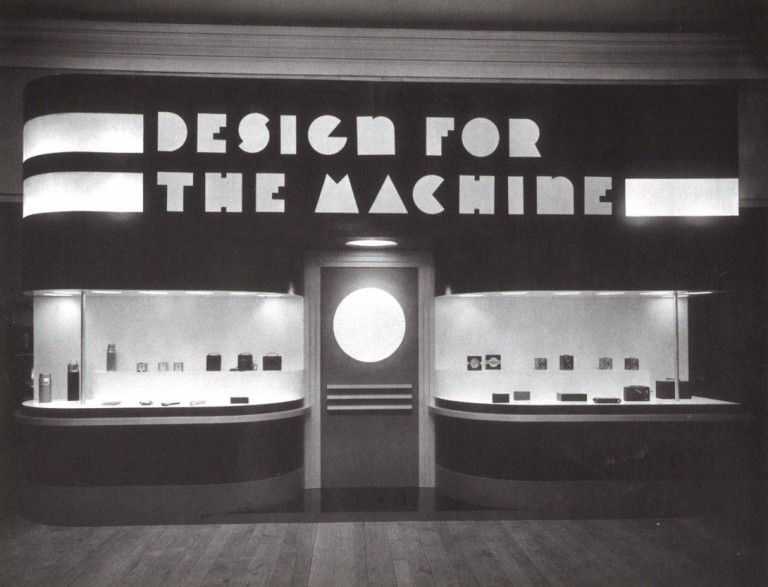

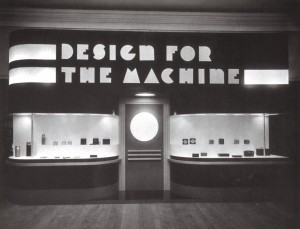

Despite the interwar romance with speed, a primary motivator for the streamlining trend was economic. In the 1930s, companies turned to professional designers to imbue products with expressive qualities without significant factory retooling. Some critics saw these attempts to stimulate consumer desire through novelty as blatantly commercial, or even morally dangerous, but streamlined products and vehicles proved hugely popular in the marketplace. Consumers in greater Philadelphia encountered the products of the young field of industrial design, whether streamlined or in a more minimal “machine” style, in contexts both commercial and cultural. Department stores were a key venue for the dissemination of new ideas in design, while arts institutions like the Philadelphia Museum of Art played a prominent role with exhibitions like the 1932 Design for the Machine: Contemporary Industrial Art. The museum displayed an array of furniture, appliances, and other home goods designed to take advantage of modern manufacturing techniques, and the installation opened with a mock storefront by noted New York industrial designer Walter Dorwin Teague (1883–1960) that echoed the Art Deco architecture appearing across the region.

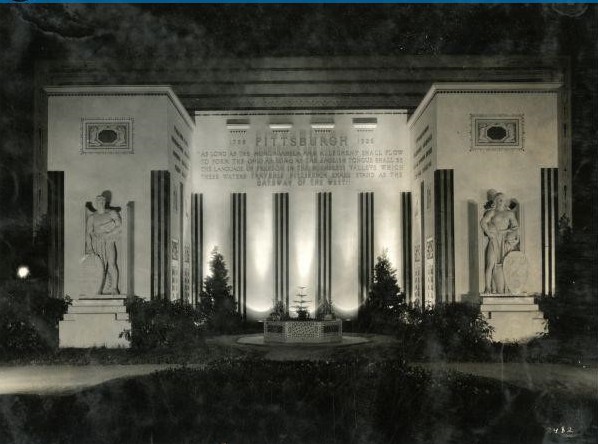

While many of the most famous firms, designers, and manufacturers featured in these displays were based in New York or Chicago, some production took place around Pennsylvania, capitalizing on its long industrial history and transportation connections. The prominent Westinghouse Company was based in Pittsburgh, while the Stehli Silks Corporation—best-known for its “Americana Prints” collection (manufactured 1925–27), commissioned from artists to capture the “modern spirit” of the country—maintained a large mill in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, until 1975, with operations peaking in the 1920s. On the more exclusive end of the textile spectrum, Philadelphia’s House of Wenger (active 1903–38) created luxurious clothes responding to the taste for streamlined modern forms in fashion as well as home goods.

Craftsmanship Valued

Mass-produced goods and the growing prominence of the industrial design profession came to dominate the decorative arts under the Art Deco umbrella, but there remained a thread of high-end making that prized individual craftsmanship and traditional techniques while it adapted to twentieth-century sensibilities. Samuel Yellin (1885–1940), a Philadelphia ironworker deeply rooted in the Arts and Crafts tradition, was one such exemplar, producing architectural elements like gates, railings, and grilles in the 1920s and 1930s that complemented the design language of the thoroughly modern buildings for which they were commissioned.

As the Depression marched on and construction and manufacturing slowed ever further, federal involvement in the arts through the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and Public Works Administration (PWA) supported some later buildings and works in the Art Deco vein. Harry Sternfeld’s post office building at Ninth and Market Streets in Center City (built 1937–41) incorporated relief sculptures by Edmond Amateis (1897–1981) in the moderne style shared by many other WPA-funded artworks. Similarly, the Edward W. Bok Technical High School (built 1935–38) was a PWA-supported project with restrained geometric Art Deco ornament.

However, a number of overlapping factors contributed to the slow decline and eventual end of Art Deco’s fashionability, including compounding economic difficulties in the 1930s and finally the onset of World War II. Stylistically, avant-garde attention in the design professions shifted toward the more strictly rationalist “International Style,” modeled after the progressive theories of European modernism. As a result, Art Deco was increasingly seen as overly decorative and retrogressive. It wasn’t until the 1960s that scholars began to reevaluate the style as a distinct expression of the economic and cultural complexities of the interwar United States. Philadelphia’s own Art Deco legacy reflects this national history in microcosm, from the commercial circumstances that birthed the city’s first skyscrapers, to the rise of radio and other forms of mass entertainment, to the WPA’s attempt to stimulate the Depression economy through art and design.

In the twenty-first century, Philadelphia’s Art Deco buildings remained in somewhat mixed condition: many have been demolished or stripped of their ornamental architectural details. Others, however, retained their characteristic Deco styling, contributing to the distinctive character of many Philadelphia neighborhoods. Accordingly, organizations like the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia continued to actively advocate for Art Deco’s importance to the region’s built heritage.

Colin Fanning is Curatorial Fellow in the Department of European Decorative Arts and Sculpture at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He holds an M.A. in Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture from the Bard Graduate Center. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Art Deco Style 1925-1940 (Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission)

- Deco City? One of the Best (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- From Classic to Electric: Art Deco and American Business (PhillyHistory Blog)

- What Lies Within: The Dazzling Art Deco Interior of 1616 Walnut Street (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Philly's Art Deco materpieces, mapped (Curbed)

- Let's Take One Last Look Back at Philly's "Art Deco Palace" (Curbed)

- Friends of the Boyd

- Perelman Building (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

- Art Deco (Victoria and Albert Museum)

- French Art Deco (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

- Art Deco Society of New York