Bank of North America

Essay

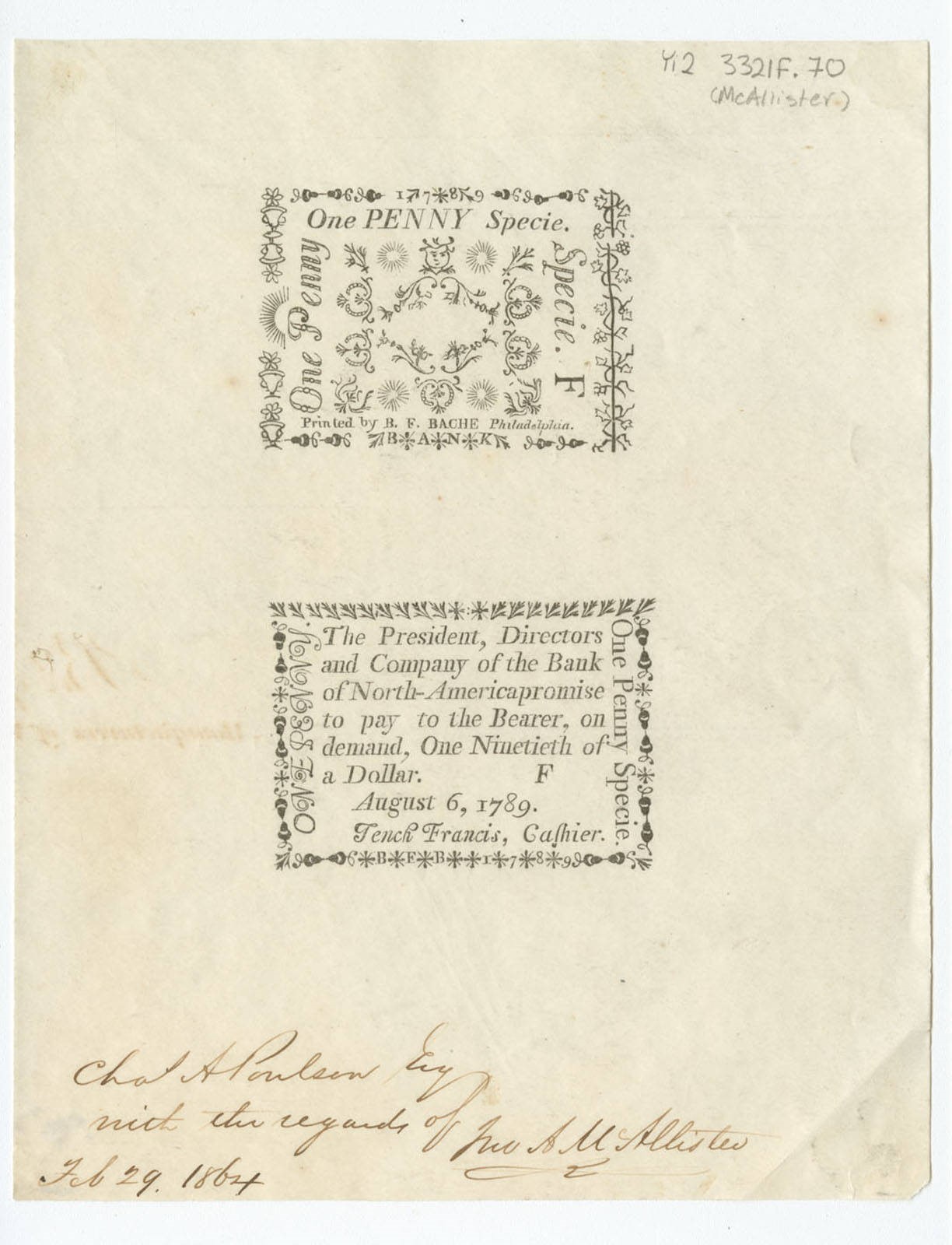

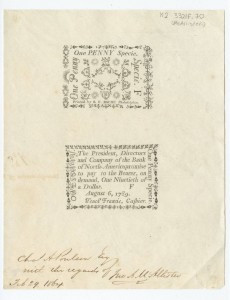

Chartered May 26, 1781, by the Continental Congress under the Articles of Confederation, the Bank of North America was the first national and truly commercial bank in the United States. Officially titled The President, Directors, and Company of the Bank of North America (BNA) until 1825, the bank was the first created by the national government to do business with and for the government. Though Pennsylvania Bank was founded in 1780, it did little business apart from subscribers who in 1782 sold their shares to BNA, which expanded its financial connections.

Robert Morris (1734-1806), congressional superintendent of finance, crafted the charter and used the bank to stabilize the national currency and save the Confederation from bankruptcy. Ninety-nine Philadelphians, along with congressmen, subscribed to bank shares and the bank opened on January 7, 1782. Morris, famous for furtive dealings, used a $450,000 French silver shipment to Congress to fund the bank, which then lent the money back to Congress. Later, when the bank feared congressional loan default, Morris sold the government’s shares to repay the bank, which then re-lent the money to Congress. Through maneuvers like this, the bank kept Congress funded through the Revolution and built itself a secure reputation.

BNA faced political controversy early on. Opponents argued it was an overreach of congressional power and a bastion for moneyed interests. Fears eased when bank directors chartered the bank in Pennsylvania giving BNA the unique distinction of holding two charters simultaneously. State politicians briefly revoked the charter in 1786. When the Confederation ceased, the national charter vanished and the bank operated under its state charter until 1864. Out of the national spotlight, the bank increasingly became a tool of the Pennsylvania government, which protected it in exchange for favorable loan conditions. BNA was a model for the federal Bank of the United States, chartered in 1791 by Congress at the behest of Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804), a protégé of Morris. BNA, however, did little business with the federal government, aside from relatively small loans to the government during the War of 1812 and the Civil War.

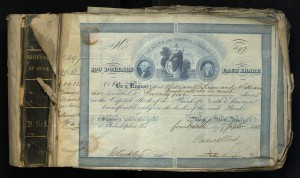

In 1863, seeking security, BNA applied to become “national” under the National Banking Act. Participating banks received national charters but were required to purchase government bonds with fixed interest rates as well as accept minimum reserve requirements. Banks benefited from consistent interest income and a federal guarantee that if the bank failed, bank depositors would be reimbursed by the sale of bank-held government bonds. Granted national status in 1864, BNA was the only bank exempted from the requirement to add the word “national” to its title.

BNA became part of the Federal Reserve System in 1914. It joined with Commercial Trust Company in 1923 to become The Bank of North America and Trust Company. In 1929, it merged into The Pennsylvania Company for Insurances on Lives and Granting Annuities, eventually renamed the Pennsylvania Company for Banking and Trust. BNA’s legacy became the First Pennsylvania Banking and Trust Company in 1955 after another merger, this time with the First National Bank of Philadelphia. In 1990, Core States acquired “First Pennsy,” which then First Union in turn acquired in 1998. In 2001, First Union merged with Wachovia, which was then purchased by Wells Fargo in 2008.

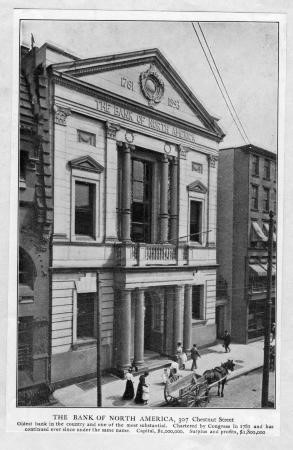

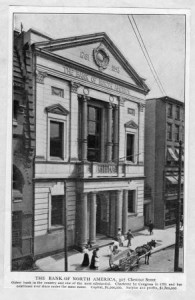

The first building BNA occupied was at 307 Chestnut Street in the home of Tench Francis (1730-1800), the first cashier. That building and its opulent nineteenth-century replacement were later demolished, however, next door at 315 Chestnut Street the original main office of First National Bank survived (later becoming home to the Chemical Heritage Foundation). BNA lived on, though its identity did not.

Robert F. Smith is Assistant Dean of Humanities and Social Sciences at Northampton Community College in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University