Barbershops and Barbers

By Sean Trainor

Essay

Throughout much of its modern American history, barbering has been derided as “servile” work, unfit for native-born, white citizens. As such, the profession has been dominated by marginalized groups. In the Philadelphia region, African Americans owned and operated the majority of barber shops during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Since then, waves of immigrant newcomers—first Germans, then Italians—have exercised an outsized influence on the trade. Despite these transformations, several characteristics of the trade have remained constant: barbering has been practiced almost exclusively by men, who in turn have catered to an overwhelmingly male clientele; the trade has offered an appealing career choice for men short on cash and long on ambition; and barbershops have remained vital sites of neighborhood sociability.

The history of barbering in Philadelphia reflects larger trends in the history of the region and nation. In the eighteenth century, men did not place a high priority on grooming. While beardedness was stigmatized, even among the “lower sort,” scruffiness was a fact of life. Infrequent trips to the barber shop—once a week or less—were the norm for most men. Barbers might face a weekend crush, as patrons prepared for religious services, but otherwise confronted weak demand for their services. This was due, in large degree, to the absence of elite customers, who were shaved and groomed by trained body servants.

To overcome this slack demand, colonial and early republic barbers turned to making and repairing wigs. Worn by elite men and women, powdered wigs were big business for eighteenth-century barbers. Barbers also made house calls, especially to the city’s leading women, where they sculpted elaborate hairstyles. Finally, Philadelphia’s barbers catered to traveling elites temporarily deprived of their household staff.

African American Dominance

While demographic information is scant, it is likely that most early Philadelphia-area barbers were men of African descent. Prior to the passage of Pennsylvania’s 1780 gradual emancipation law, many enslaved Philadelphians worked in personal service. As black men moved out of bondage, many took the skills they had acquired during enslavement and turned them into a livelihood.

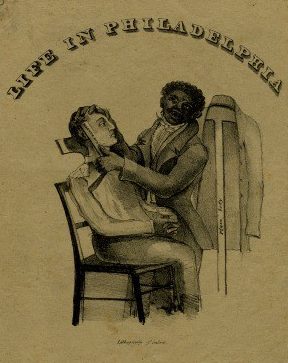

Philadelphia’s barbering trade continued to be dominated by men of color in the early nineteenth century. Although it offered opportunities for wealth, most whites regarded barbering as beneath the dignity of republican citizens. Thus, both freeborn Philadelphians of color and new arrivals born into slavery found few white competitors in the trade. Due to these favorable prospects, the number of black barbers grew dramatically over the antebellum period—with grooming professionals representing a large share of the region’s black middle class. So closely linked were black barbers and wealth, in fact, that when artist Anthony Imbert (1794/5–1834) illustrated a wrapper for the racist Life in Philadelphia series by Edward Clay (1799-1857), he chose a barber of color as the subject.

Many of these black barbers made their living by grooming wealthy white men (most barbers had stopped styling women’s hair after the Revolution). Though standards of comportment had increased since the eighteenth century, regular grooming remained the province of elites—many of whom eschewed body servants in the nineteenth century. To satisfy the tastes and prejudices of these elites, Philadelphia’s black barbers built and operated luxurious, whites-only pleasure palaces. Among the most prominent of these was the shop of Joshua Eddy (1798–1882) on Chestnut Street, which helped make Eddy the city’s wealthiest barber of color.

Although most barbers of color operated segregated shops, many actively participated in organizations committed to combating racism. Barber Joseph Cassey (1789–1848), for instance, served as the city’s first agent of the abolitionist newspaper the Liberator. On the whole, however, barbers had a well-earned reputation for conservatism—due, no doubt, to their dependence on white patronage.

Influence of German Immigrants

Beginning in the 1840s, the demographic makeup of Philadelphia’s barbers underwent a dramatic shift. Representing a mere fifth of Philadelphia’s barbers in 1850, whites accounted for over half a decade later—a percentage that would continue to grow in coming decades. Of the white barbers who plied their trade in 1860, roughly two-thirds were German immigrants. Arriving in droves in the 1840s, Germans brought a long tradition of barbering and none of the cultural baggage that barred native-born whites from the profession.

Due to growing competition from Germans, black barbers took an increasingly grim view of their profession’s future. By the 1850s, the average barber of color was middle-aged and fewer young men entered the profession as teenage apprentices. Only 5 percent stayed behind the chair for more than a decade. And a significant number of Philadelphia’s poorest black haircutters repeatedly wound up in the city’s almshouse.

A hardening of white racism and a growing discomfort with the touch of black professionals also contributed to the decline of black barbering. This discomfort was exacerbated by the popularity of fictional British barber Sweeney Todd, who was first introduced in the anonymously authored novel The String of Pearls, which appeared in serial form in the mid-1840s. This novel, along with numerous Sweeney Todd copycats who appeared in print over the following decade, inspired widespread fears about murderous barbers. While this tale negatively impacted all barbers, it had a particularly pernicious effect on those whom white customers were already inclined to fear.

For Philadelphia’s black barbers, white anxieties about race, intimacy, and violence proved nearly insurmountable. Although African Americans continued to make up a larger percentage of the barbering population in Philadelphia than in other northern cities, their share shrunk with each passing decade. Representing a fifth of Philadelphia barbers in 1880, barbers of color constituted a mere tenth by the turn of the twentieth century.

“Color-Line” Shops End

During these decades, the era of the “color-line” shop—in which black barbers served white patrons—came to an end. With few white Philadelphians willing to submit to a black man’s touch, barbers of color turned instead to the city’s growing black community for patronage. This dramatic shift was reflected in the geography of Philadelphia’s black-owned shops. Concentrated along Philadelphia’s white-dominated Market Street in the twilight years of color-line establishments, by 1920, most black-owned shops had either moved to South Street, near the predominantly black Seventh Ward, or to North Broad, near its intersection with Fairmount. Though born of hardship and discrimination, these “black barbershops” became beloved neighborhood institutions for both longtime residents and for the tens of thousands of southern African Americans who flocked to the city as part of the Great Migration. Centers of sociability, activism, and community organizing, these shops served, in the words of an adage, as “the black man’s country club.”

White barbers, meanwhile, took important steps to exorcise the specters of Sweeney Todd and black dominance from their trade. They did so by assuring would-be customers—many of whom fled the shop during the postbellum heyday of the beard—that they would be greeted by trained and certified white professionals. This was an especially urgent task for the 80 percent of white Philadelphia barbers who were either immigrants or first-generation Americans—and whose trustworthiness was therefore suspect in the eyes of many customers.

To achieve these goals, white barbers organized professional organizations. Two of the most important—the Journeyman Barbers International Union and the Associated Master Barbers of America—had strong presences in Philadelphia and the surrounding area. Save for a brief period of interracial cooperation during the 1930s, these organizations remained rigidly segregated until the mid-twentieth century. While the Philadelphia chapters of the JBIU and AMBA raised the profile of white barbers, they showed scant regard for black barbers or their role in the trade’s history.

The white barbers who filled the ranks of these professional organizations were overwhelmingly of Italian descent. Indeed, by the early twentieth century, first- and second-generation Italian immigrants had successfully challenged Germans and their descendants for dominance of the trade. Trained at institutions such as Philadelphia’s Tri-City Barber School—Pennsylvania’s oldest barbering academy—as well as in traditional apprenticeships, Italian American barbers included local celebrities such as Vincent Ionata (b. 1920), proprietor of a Suburban Station shop patronized by local politicos, and Charles Pittello (1915–2000), who catered to Frank Sinatra (1915–98), Bob Hope (1903–2003), and other stars in his Adelphia and Warwick Hotel shops.

African American Resurgence

By the late twentieth century, however, African Americans once more returned to their erstwhile position as the region’s leading barbers. This was due, in large measure, to “white flight”: the panicked departure of many white residents and their barbers for the region’s growing suburbs. But it was also due to the enduring importance of barbers and their businesses in African American communities. Though shops of the late twentieth century were far less luxurious than their nineteenth-century counterparts—with plastic chairs and linoleum floors replacing ornately carved wooden furniture and glistening wall-length mirrors—barbers continued to serve as marriage counselors, youth mentors, and community organizers. In Wynnefield, for instance, barber Robert Woodard hosted a 2004 discussion by civil rights leader Jesse Jackson on gun violence. Philly Cuts’s owner Darryl Thomas (b. 1972) invited University of Pennsylvania medical students to test patrons’ blood pressure in 2011. And the Camden shop of Russell Farmer (b. c. 1920) played host to a citywide celebration of Black History Month in 2012.

For the proprietors of these shops, as well as their overwhelmingly male workforce, barbering proved an attractive career option. Not only has it provided a steady income and a position of respect, but it also offered ex-convicts—numerous in the age of mass incarceration—opportunities for advancement that would be difficult to come by in less personal, less understanding workplaces.

Still, barbers have faced a number of daunting challenges. In the 1960s and 1970s, for instance, the long hair and beard fashion nearly dealt a death blow to the profession—with twenty thousand barbers leaving their posts nationwide, according to industry group Hair International. This was particularly devastating for African American barbers, as the labor intensive “process,” or “conk” as it was sometimes called, gave way to the comparatively low-maintenance Afro. Barbers also contended with the specter of violence. Often open late at night with large amounts of cash on hand, barbershops have been frequent targets of robbers, with numerous barbers shot and, in some cases, killed since the 1980s. Lastly, twenty-first-century barbers faced stiff competition from salons—with more than five times as many salons as barbershops in Pennsylvania in 2002, according to the state Department of Cosmetology, as there were barbershops.

Despite these challenges, however, the barbering profession endured. In fact, in the early twenty-first century, barbering underwent something of a renaissance with upscale establishments such as Center City’s Groom or Pompadours in Maple Shade, New Jersey, joining the ranks of better-established shops. Catering to a growing population of well-off white males, these shops both reflected and participated in the process of gentrification sweeping the region during the early twenty-first century.

Nevertheless, a number of the trade’s basic features stayed constant. Barbering remained, in large measure, a profession of and for men. It continued to be an attractive option for ambitious men of modest means. And Philadelphians continued to enhance their appearance and participate in shops’ social pleasures. Part social club, part community center, Philadelphia’s modern shops maintained a tradition reaching back to the city’s colonial past.

Sean Trainor teaches history and humanities at the University of Florida, Penn State University, and Santa Fe College. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, Business History Review, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Early American Studies, Salon, and TIME. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Wissahickon Barber Shop celebrates 100 years (WHYY, July 19, 2011)

- Frank the barber turns 90 (WHYY, July 23, 2012)

- Dispensing wisdom with style, barber presides in Camden 'oasis' (WHYY, February 26, 2013)

- Wissahickon Barber Shop ― the center of civic life for a century ― quietly closes (WHYY, September 30, 2013)