Educational Reform

By Cody Dodge Ewert | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Since the early nineteenth century, several reform efforts have aimed to improve Philadelphia-area public schools. While the historical context and the individual actors changed over time, a firm belief that basic education for all could foster social equality animated reform in every era. Of course, race- and class-based inequality did not disappear, but educational reform had a lasting influence nonetheless, shaping both the day-to-day operations of area schools and their role in society.

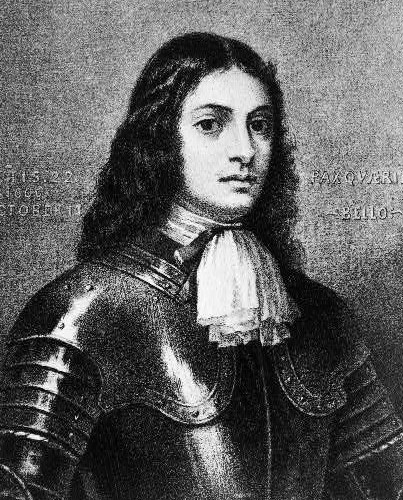

Educational matters have long attracted the attention of political leaders and citizen groups in the Philadelphia area. Indeed, Pennsylvania founder William Penn (1644-1718) believed the public welfare could be uplifted through universal religious education. In Philadelphia, the earliest attempt to make this vision a reality came when the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) opened a free school in 1689. While the school welcomed students regardless of their class or religious backgrounds, the growing city’s educational needs quickly outpaced its ability to accommodate students. For the bulk of the eighteenth century most area children learned basic reading and writing skills at home, if at all.

An effort to promote the development of free “charity schools” in the late eighteenth century signaled the area’s first major educational reform movement. Lacking state or municipal support, religious voluntary associations spearheaded efforts to bring basic education to the disadvantaged. Although most targeted white children, some charity schools also aimed to enroll the children of Black freedmen. Philadelphia Quakers opened a school for Black boys in 1770, followed by a girls’ school in 1787, and one for adults in 1789. Similar schools appeared in Burlington, New Jersey, and Wilmington, Delaware, during these years. While charity schools ostensibly promoted social stability by providing poor children with educational and vocational opportunities, their goals for Black children and adults were limited. Local leaders often considered education for Black people to be merely a bulwark against their perceived penchant for criminal activity and vice. While some thought education could narrow racial differences, beliefs about the different educational needs of Black and white children–and school segregation–persisted. Racial inequality compounded the already significant gap in resources between schools serving poor children and those catering to wealthier families.

By the time of the Civil War, once-independent area charity schools formed the basis of a public education system. This process began when Pennsylvania’s state legislature passed a measure placing Philadelphia’s charity schools under public control in 1818, shifting their management from voluntary associations to appointed officials and locally-elected school boards. Both reformers and workingmen claimed that making schools a public good could eliminate lingering inequalities. In 1834, a group of tradesmen in New Castle, Delaware, for instance, demanded “a rational system of education to be paid for out of public funds,” decrying the old system as “destructive of the equality which is predicated in the Declaration of Independence.” By 1836 this reform came to fruition across Pennsylvania, as the state empowered local officials to open publicly supported schools to students regardless of income, a move that led to the creation of local public school systems.

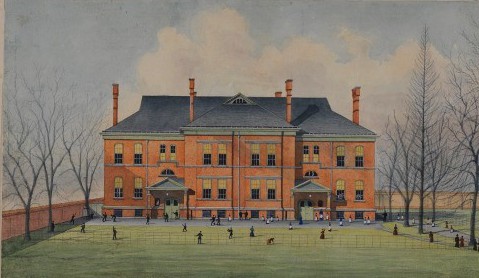

By the turn of the twentieth century growing populations in Philadelphia, Camden, and Wilmington strained their loosely organized, locally controlled school systems. In Philadelphia, dozens of ward-based school boards hired teachers, implemented curricula, and collected taxes as each deemed necessary. An early attempt to reorganize the Philadelphia system came in 1882 when Philadelphia’s first city-wide superintendent of schools took office. In addition to seeking centralized control, the city’s educational leaders began pushing for mandatory attendance and new school construction in order to replace the antiquated and insufficient facilities that left over 20,000 students without seats in classrooms.

Despite the progressives’ zeal, opposition was fierce. Defenders of localism dismissed the era’s educational experts as power-hungry elites seeking to enhance their status by silencing parents. In response, reformers eschewed the rhetoric of modernization, instead emphasizing the existing system’s widespread corruption, which muckraking journalists like Adele Shaw (1865-1941) ably documented. This placed pressure on local politicians, and in 1905 the state legislature responded by weakening the individual ward boards and reducing the size of the central school board from forty-two to twenty-one members. Reformers deemed this law a “revolution” and touted its transformative potential for future generations. Their enthusiasm quickly spread throughout the state and region. In 1911, all state schools became subject to the “Pennsylvania School Code,” which centralized administrative control and strengthened existing laws that made education compulsory.

In the context of popular concern about rapid urbanization and rising immigration, reformers’ lofty rhetoric heralding the far-reaching consequences of modern schools helped secure support for their agenda. In addition to average citizens, private philanthropists came to believe in educational reform’s progressive potential, donating large sums to improve area schools. This vision came to Delaware’s school system in 1917 when Wilmington-based industrialist Pierre S. du Pont (1870-1954) began pouring millions of dollars into the state’s public schools. High-profile efforts like this pushed legislators to act, and in 1919 Delaware adopted a measure similar to Pennsylvania’s 1911 law, bringing modern educational practices to a state that had been operating its schools as if it was still the nineteenth century.

Although professional educators, politicians, and philanthropists spearheaded this wave of reform, middle-class parents and concerned citizens alike soon took an important role. A rising number of “home and school leagues” pushed for smaller school boards and increased teacher pay. Similarly, voluntary associations–particularly women’s clubs–played a key part in shaping the schools in Philadelphia’s growing suburbs. As early as 1920, many middle-class suburban parents became vocal advocates for local schools, a decided shift from the ambivalence many area parents expressed toward public schooling in previous decades.

Black families and community activists also pressed for reforms in the first part of the twentieth century. A campaign in the 1930s led by civil rights activist Floyd Logan (1901-78) convinced Philadelphia to appoint its first Black school board member and begin assigning African American teachers to the city’s junior and senior high schools. Still, segregation only increased in area schools, as thousands of Black migrants moved to the region both before and after World War II. Upon arrival, they faced widespread housing discrimination that often confined their children to neglected schools in poor neighborhoods. Following the Supreme Court’s Brown v Board of Education decision in 1954, Philadelphia’s NAACP mounted a citywide desegregation effort. While the school board officially condemned discrimination in 1959, it did little else. In response, parent associations like the one at the Emlen School in the Germantown neighborhood, where Black pupils made up 86 percent of the student body in the 1950s, teamed with the NAACP to challenge the city’s practice of placing overflow students in mobile units rather than redrawing district lines or busing them. In 1963, the threat of a prolonged legal battle led the board of education to expand its anti-discrimination resolution, making school integration official policy. But opposition from many middle-class whites ruled out proposed solutions like busing to existing schools or new schools built in clusters (otherwise known as educational parks). One white neighborhood organization even carried a coffin representing “the death of the neighborhood school” into a school board meeting. In Philadelphia, desegregation efforts resulted in only meager progress by the 1970s while engendering significant opposition.

A related effort aimed at ending class-based educational inequality stirred New Jersey. A state Supreme Court decision (Robinson v Cahill, 1973) determined that New Jersey’s system of funding public schools primarily by local taxation reinforced both educational and economic inequalities. To compensate, the state needed to move revenue to financially disadvantaged districts. Robinson, which charged New Jersey with violating its own constitution and the equal protection clause of the United States Constitution, served as both a legal and political challenge to the state’s overwhelming educational disparities. In 1990, New Jersey had to move even more aggressively on the issue of inequality following the state Supreme Court’s landmark Abbott v Burke II ruling, which found that “the poorer the district and the greater its need, the less the money available and the worse the education.” This finding led the court to establish the funding principle of “parity-plus” for underprivileged districts. It required that additional funds go to districts that met the state’s new need-based qualifications.

The dilemmas of race- and class-based inequality in public education also came to a head in Delaware in these years, as urban and suburban schools filled with disproportionate numbers of Black and white students, respectively. These trends continued until a 1975 District Court decision—later affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court (Buchanan v. Evans)—forced the consolidation of the public schools in New Castle County. This ended the Wilmington area’s neighborhood-based public school system and created four new districts that brought Black children from the inner city into the same schools as white suburbanites. As was the case with similar measures in New Jersey, public reaction was mixed. While many cheered the decision, others, especially parents fearing for the quality of their children’s education, bemoaned the dissolution of their community schools. Some turned to private schools, homeschooling, or, beginning in 2001, charter schools.

While measures aimed at creating a more equitable funding system in New Jersey and integrating schools in Delaware sparked controversy, so too would efforts to bring private management to public schools. In late 2001, citing over half of Pennsylvania students’ failure to demonstrate proficiency on standardized reading tests, Governor Mark Schweiker (b. 1953) spearheaded an effort that forced the School District of Philadelphia to abolish the city’s school board and place its schools under the control of a “School Reform Commission.” Despite staunch opposition from many teachers, grassroots activists, and union leaders, the state won the approval of Philadelphia Mayor John F. Street (b. 1943). After assuming control, the commission appointed a private company to manage several under-performing schools. This decision opened the door for an expansive system of publicly funded, privately controlled charter schools just as the federal government’s No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) began demanding that states receiving federal funds show “adequate yearly progress” based on standardized test results. While the charter school movement chiefly affected urban schools, some suburban districts like Chester-Upland, which placed nine of its ten schools under private control, also embraced these measures. By mid-2002, private groups managed forty-five of Philadelphia’s 264 public schools.

Politicians, parents, and educators were divided on charter schools by 2010. Some claimed they held the key to academic success for low-income, minority students; others condemned them as an antidemocratic scheme to place a public obligation into private hands. Citing modest gains on standardized tests, supporters touted them as academic game-changers. But opponents pointed to a number of ill effects, warning, for example, that charters turned away too many special needs students. Lack of public oversight also concerned many critics. By 2011, nineteen of the Philadelphia’s seventy-four charter schools had been investigated for fraud, mismanagement, and other conflicts of interest. Rifts also grew over the emphasis on standardized testing and accountability that accompanied both NCLB and the embrace of charters.

Through it all, both advocates of reforms like charters and high-stakes testing and champions of traditionalism in education described their efforts in almost messianic terms. Each aimed not only to improve the quality of education, but also to alleviate racial and economic inequalities. Indeed, several generations of Philadelphia-area school reformers have believed education could solve these enduring problems. The way there, however, has been constantly contested.

Cody Dodge Ewert is a Ph.D. candidate in American history at New York University. His dissertation examines the relationship among school reform, patriotism, and political culture during the Progressive Era. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- How is Special Education Paid for in Pennsylvania Public Schools? (WHYY, April 29, 2015)

- Camden School District Asks for Public Input on Education Priorities (WHYY, August 6, 2015)

- Philly SRC votes to phase out two middle schools, not close immediately (WHYY, February 19, 2016)

- Philly approves one new charter school, rejects another two (WHYY, February 9, 2017)

Links

- Legal History of Brown v. Board of Education (United States Courts)

- History of the National Education Association (National Education Association)

- Recent National Education Reform Information (U.S. Department of Education)

- Pennsylvania Department of Education Explanation of Charter Schools (Pennsylvania Department of Education)

- An Explanation of the Common Core Standards (Common Core Standards)

- History of William Penn Charter School (William Penn Charter School)

National History Day Resources

- Complaint in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 1951 (DocsTeach)

- President's Daily Diary Entry, April 11, 1965 (DocsTeach)

- Educational Equality League v. Tate, 1971 (Google Scholar)

- Mayor of Philadelphia v. Educational Equality League, et. al., 1974 (Google Scholar)

- Abbott v. Burke, 575 A. 2d 359 - NJ: Supreme Court 1990 (Google Scholar)