Elfreth’s Alley

By Joanne Danifo | Places and New Knowledge

Essay

Nestled between Second Street and the Delaware River, thirty-two Federal and Georgian residences stand as reminders of the early days of Philadelphia. Elfreth’s Alley survived in the twenty-first century as a residential street, historic landmark, and interpreted site labeled the “Nation’s Oldest Residential Street.” The heroic efforts of residents and local historians from the 1930s to 1960s preserved the Alley as a typical colonial street, but it took decades of new scholarship for the Elfreth’s Alley Association to create an interpretation encompassing the everyday lives of all generations who lived on this street.

Elfreth’s Alley, which has existed for three centuries as a residential enclave, was not included in William Penn’s original plans for Philadelphia. Demand for land in proximity to the Delaware River erased Penn’s dream of a bucolic country town composed of wide streets. As Philadelphia became a bustling city, artisans and merchants purchased or rented the in-demand property close to the ports where goods and materials arrived daily. By 1700, most of the population of Philadelphia settled within four blocks of the Delaware River. This led to overcrowding, and landowners recognized that tradesmen needed alternate routes to the river through the crowded streets Penn had laid out decades earlier. Landowners Arthur Wells and John Gilbert combined their properties between Front and Second Streets to open Elfreth’s Alley, named after silversmith Jeremiah Elfreth, as a cart path in 1706.

Taking advantage of trading on the waterfront, artisans soon created a small community of people living and working on the Alley. The homes they inhabited ranged between two and four stories, and residents often used the front room on the first floor as workplaces and shops, while the kitchen and upper levels served as private space for the family. Residence #112 alone was home to a carver, boat builder, baker, and joiner throughout the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Several Alley residents also earned income by renting rooms to sailors, and others engaged in work on the waterfront. Census records suggest that Widow Esther Meyer in #119 and Sarah Melton in #124 rented rooms to sailors, and Ann Taylor, the widow of bricklayer Enoch Taylor, ran a boarding house from half of her home in #116.

Factories Surrounded the Alley

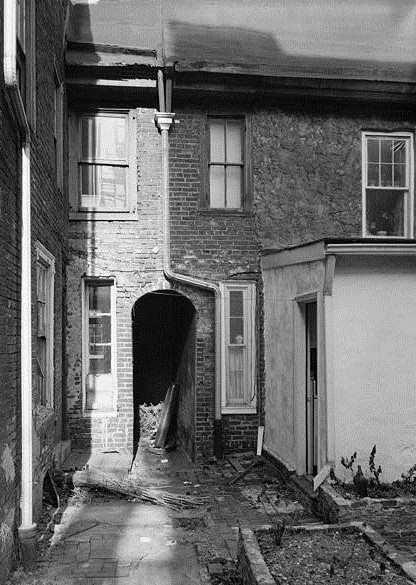

The move of manufacturing from the home to the factory during the Industrial Revolution transformed the Alley and surrounding neighborhood in the mid-nineteenth century. Factories lined Second Street, with no fewer than four surrounding the homes on the Alley. As the years passed, immigrants flocked to the street to take advantage of the many factory jobs in the area, first Irish and Italians and later Russians. In 1900, the Freemans, a Russian family, lived in #125 with another family, and some of the residents worked in local button factory. With the increase in demand for housing near the factories, several Alley residents built tenements in the courtyards and rented them for extra income. A typical tenement, like the one behind #126, consisted of two to three floors with one room on each floor, and families used side alleys to access them. Each home no longer housed an artisan and his small family or a widow with two tenants. According to census records, between 1870 and 1930 no fewer than two families lived in #123, twenty-six people resided at #124-126, and more than three hundred people lived in the homes and tenement buildings by 1880.

By the 1930s, decades of overcrowded homes and encroaching industrial buildings had taken their toll on the street. While the houses on the Alley were in high demand when Philadelphia was a leading colonial port city and manufacturing hub, these eras had passed. Many factories left the neighborhood, and residents moved away as the jobs did. Condemned homes and abandoned tenements plagued the Alley, and the area was considered a slum. Conditions only worsened after World War II as the city witnessed a population exodus to newly developing suburbs. Real estate values plummeted in the area around Elfreth’s Alley.

Touched by the Colonial Revival movement that looked to the birth of the nation as a simpler, romantic time, Alley residents attempted to reverse the decline of their neighborhood. The city condemned #126, and Wetherill Paint Company rented the run-down #124 to tenants. Inspired by the preservation efforts of the Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks at the Powel House, Alley resident Dolly Ottey drew on Colonial Revivalist themes to combat the Alley’s deterioration. The Elfreth’s Alley Association, established in 1934, raised funds to purchase and restore #126 by 1937 through house tours, fund-raising events, and an annual summer street festival filled with colonial costumes and eighteenth-century games. The Association established a house museum in #126. After saving #124 from demolition by Wetherill Paint Company in the 1940s, the Association used the house as a rental property until turning it into its headquarters in the late 1990s.

Officially Historic

Facing another challenge to the survival of the residences in the 1950s, the Elfreth’s Alley Association secured National Historic Landmark status to ensure that Interstate 95 construction did not erase the homes on the street. They restored the Georgian and Federal architecture, demolished tenements, and placed telephone wiring under new stone street pavement. Except for a few factories that survived on Second Street, most of the vestiges of nineteenth and early twentieth century life and industry on the Alley and in the surrounding neighborhood disappeared, and the neighborhood seemed frozen in time.

In the early 1960s, the Association hired an architectural historian to create a house museum on the Alley celebrating the colonial period. The Association acquired furniture from the Philadelphia Museum of Art to recreate the residence of an eighteenth-century artisan in #126, further helping establish the Alley as a showcase for colonial Philadelphia. That remained the main story told to visitors for several decades. The rise of social history and developments in the field of public history in the following decade led the Association to take steps toward transforming the colonial interpretation of the Alley. As a result, the Association broadened its story to include the full range of alley occupants and the urban developments that affected their lives. Beginning in the 1990s and continuing into the present-day, relationships with local scholars, new research methods, and an emphasis on the identity of the street as continuously residential helped the Association expand the scope of the Alley’s story and define this urban space so rich with associations over several centuries.

Joanne Danifo holds a master’s degree in history from Rutgers University with a focus in administration and programming at historic sites. She has worked for the Elfreth’s Alley Association, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and in freelance research positions. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2012, Rutgers University