Fire Escapes

By Sara E. Wermiel | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Introduced in the nineteenth century, fire escapes supplemented interior stairways to allow people on the upper floors of buildings to escape in case of fire. Fire escapes can be portable or fixed on or in buildings, and they have taken many forms. Philadelphia enacted the first municipal law mandating fire escapes on all sorts of buildings and is associated with an important innovation in fire escape design: the Philadelphia fire tower.

In 1876, Philadelphia enacted the first municipal fire escape law in the United States. This ordinance had been proposed by the chief engineer of Philadelphia’s newly organized, paid fire department, partly in anticipation of the crowds expected to attend the Centennial Exhibition but mainly because of deadly fires in factories. The law created a Board of Fire Escapes, which could order the construction of fire escapes on any building, in whatever form the board believed best. Significantly, the law applied to existing buildings as well as new construction, and by specifying that fire escapes be “erected,” assumed these would be structures in or on buildings.

Soon thereafter, in 1879, Pennsylvania’s legislature passed a fire escape law. Like the Philadelphia law, the state act specified that fire escapes be “permanent,” and now they also had to be “external.” It obliged not only building owners, but also building managers, to put in the fire escapes. The law was ineffective, however. It gave no guidance on what a fire escape should be like, apart from being permanent and external. Moreover, the legislature provided no resources, no state officers, and no funds to enforce the act.

Philadelphia’s City Councils took the occasion of this law to discontinue funding for the Fire Escape Board, thereby allowing the city’s ordinance to lapse. Without any enforcement, few building owners voluntarily complied with either law. For example, five years after the ordinance passed, and two after the state law, few factories in Philadelphia had fire escapes.

Randolph Mills Fire of 1881

A deadly fire in a Philadelphia factory, Randolph Mills, on the night of October 12, 1881, exposed the possible catastrophic consequences of a lack of adequate egress. This large textile factory, on Randolph Street in North Philadelphia, was built in 1878–ironically, on the ruins of a mill that burned down the previous year. Before the first mill burned down, the Fire Escape Board had advised the owner to put up a fire escape. But even as he rebuilt the mill, the building owner did not do so–he considered fire escapes unnecessary. About forty people were working the night shift at the time of the second fire. The mill’s new electric lights were believed to have been the cause of the fire, which started on the second floor. Workers on the floors above became trapped when fire engulfed the building’s stairway. Many jumped from windows. Nine died in the fire or after jumping, five of them teenagers. Sixteen other employees suffered serious injuries.

The fire stirred public indignation and demands for government to compel mill owners to provide adequate means of emergency egress. The coroner’s jury found the building owner criminally responsible for the loss of life, and it also found the City of Philadelphia responsible for not enforcing the fire escape law. The horror of the tragedy–burned, crushed, and broken bodies–motivated city leaders to do something about fire escapes. A few days after the fire, Mayor Samuel King (1816-99, in office 1881-84) ordered the police to notify owners of factories, tenements, and other buildings to erect fire escapes, pursuant to the 1879 state act. However, police officers had no background in the design and installation of fire escapes.

Iron Fire Escapes and the Philadelphia Fire Tower

Soon after the Randolph Mills fire, the Franklin Institute formed a committee to take up the question of fire escapes. This was probably the first time a group of technically-minded men considered the matter of emergency egress and fire escape design. The committee made practical suggestions, but its main contribution was to propose a novel type of fire escape: an enclosed stairway tower that could not fill with smoke and fire. This could be connected to all floors of a mill by bridges, and in cases where buildings covered their lots, it could be an internal enclosed stairway accessed from the outside, by balconies. The committee’s recommendations were not immediately adopted, however.

In 1885, the state legislature remedied adverse court rulings by amending the 1879 law. Like the earlier law, this act applied to many kinds of buildings in addition to factories, including hotels, schools, hospitals, warehouses, tenement houses and, new to this act, public halls. It included specifications for a fire escape: an outside, iron stairway, not too steep, with treads.

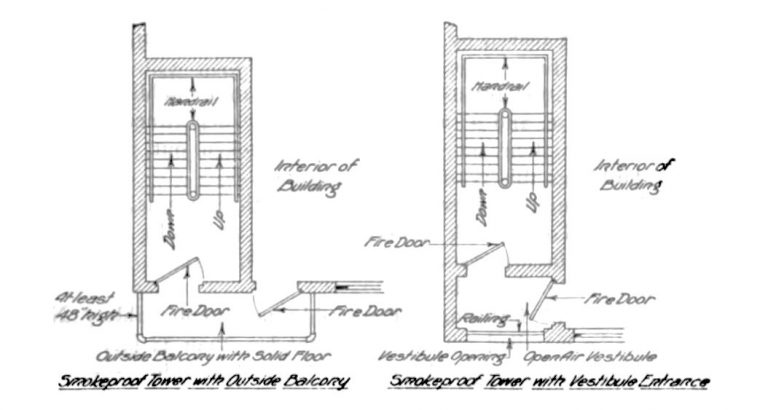

Later in the nineteenth century, fire escapes consisting of a stairway enclosed in masonry walls came to be required in factories and then other kinds of buildings in Philadelphia–a design that evolved to become the “Philadelphia fire tower.” Philadelphia’s 1893 building law called for various kinds of buildings to have stairways enclosed in brick walls or “incombustible” partitions. Large stores were to have “a tower fire escape enclosed in incombustible material adjoining one of its fronts.” Larger mills were to have “brick enclosed fire escapes” or other approved escapes. The design of these enclosed stairs developed into the Philadelphia fire tower–constructed so that smoke and flames could not enter. The towers were built usually in one of two forms. The “balcony type” had balconies at each floor connecting doors from the building with doors in the stair tower. A second “vestibule type” had a landing recessed into the wall of a building connecting a floor to the tower. Occupants would exit onto the balcony or the landing and then enter the door of the tower.

Fire protection authorities considered the Philadelphia fire tower, also called a smokeproof tower, the best means of emergency egress. H. Walter Forster (1883-1968), an engineer and at the time (1920) chairman of the National Fire Protection Association’s Committee on Safety to Life, wrote that they provided “the safest means of downward exit for able-bodied persons.” Yet this type of fire escape was rarely built outside of Philadelphia. Other kinds of fire escapes, such as iron skeletons, were allowed in certain cases in Philadelphia and became a common type in other cities.

These towers survived into the twenty-first century in many older Philadelphia buildings. The old type of external, iron fire escapes also remained visible on buildings, although these have long been criticized as sub-optimal means of emergency egress. A Philadelphia ordinance passed in 2017 required inspections of external fire escapes and fire balconies every five years and repair if needed. Meanwhile, the Philadelphia fire tower remained a progressive symbol of the city’s efforts to save lives in building fires and a forerunner of the enclosed, protected stairway, the fire escape of the twenty-first century.

Sara E. Wermiel is a historian of building construction and the construction industry. She has a Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Her book, The Fireproof Building: Technology and Public Safety in the Nineteenth-Century American City (2000), treats the history of structural fire protection in buildings. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University