Glassmakers and Glass Manufacturing

Essay

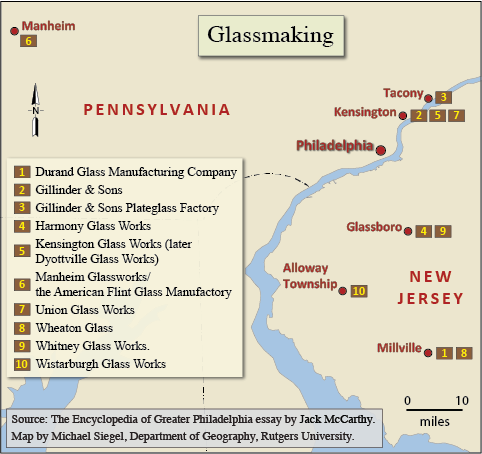

Glassmaking was one of Philadelphia’s earliest industries. Although it never became a major part of the city’s economy to the extent that industries such as textiles and metalworking did, a number of large glass manufacturers operated in and around Philadelphia from the early eighteenth to early twentieth centuries. The industry went into decline within the city itself in the mid-twentieth century, but it remained a key part of the economy of southern New Jersey. Beginning in the 1730s, areas such as Alloway and Glassboro, New Jersey, became important glassmaking centers, while Millville was home to large-scale glass manufacturing from the early nineteenth through early twenty-first century.

Of the dozen or so glassworks in colonial America, four operated in the Philadelphia region. The first was established in 1683 by the Free Society of Traders. Society treasurer James Claypoole (1634–87) wrote in July 1682 of the company’s intention “to set up a glass house for bottles, drinking glass, and window glass,” and the following year William Penn (1644–1718) noted that the society’s glasshouse was “conveniently posted for Water-carriage.” In September 1683 English glassmaker Joshua Tittery (?–c. 1709) arrived in Philadelphia as a servant of the Free Society, presumably to operate or work at the society’s glasshouse.

The location of this glassworks is uncertain; it could have been near the village of Frankford, where the Free Society owned a large tract of land and Frankford Creek would have provided water transport, or along the Delaware River in Shackamaxon (later the Kensington/Fishtown area), where there were several glasshouses in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The Free Society failed as a business enterprise after only a few years, apparently including its glassworks. The July 1685 minutes of Philadelphia Meeting, the area’s ruling Quaker institution, included a complaint from “Joshua Tittery a glass maker belonging to the Society … that they deny him his wages.” By the 1690s Tittery was working as a potter.

Wistarburgh Glass Works

The most successful glassmaking operation in colonial America was that of Caspar Wistar (1696–1752), an entrepreneurial German immigrant based in Philadelphia who in 1739 set up the Wistarburgh Glass Works in partnership with four German glassblowers in what is now Alloway Township, Salem County, New Jersey. By the mid-1750s Wistarburgh had twenty-eight workers who primarily made bottles and window panes, along with tableware such as drinking glasses and decanters (although most table glass was imported in this period). In the 1740s Wistar worked with his neighbor Benjamin Franklin (1706–90) on making tubes and globes for Franklin’s scientific experiments.

In a 1768 report to Britain on manufacturing in New Jersey, Governor William Franklin (Benjamin’s son, c.1730–1813) noted that “The Profits by this [Wistarburgh] Work have not hitherto been sufficient … to induce any Persons to set up more of the like kind in this Colony.” Given political tensions at the time, Governor Franklin was probably deliberately downplaying Wistarburg’s success to prevent England from perceiving it as a threat to its own glass-making industry. Following Caspar Wistar’s death, his son Richard (1727–81) continued the glassworks until it closed during the Revolutionary War.

Wistarburgh served as a training ground for a number of colonial glassmakers, many of whom stayed in the area. With an established community of skilled glassmakers, rich local deposits of sand and clay that were the primary raw materials for glass production, and plentiful oak trees to fuel the wood-fired furnaces, southern New Jersey became an important glass manufacturing region. German immigrant Soloman Stanger (1743–94) worked at Wistarburgh for several years before establishing his own glassworks eighteen miles away in 1781. Financial difficulties forced Stanger to sell the business after only a few years, but he and his descendants continued working in the area, while the community they founded became Glassboro, New Jersey, longtime home to a number of important glassworks.

German immigrants played a key role in colonial glassmaking elsewhere in the broader Philadelphia region as well. When the ship Nancy arrived in Philadelphia in August 1750, onboard were Johann Georg Musse (d. 1760), who built a glassworks in 1752 in Hilltown Township, Bucks County, that operated until 1784, and Heinrich Wilhelm Stiegel (1729–85), who eventually settled in Lancaster County, where he prospered as an ironmaster and glassmaker. Stiegel established two glassworks in the 1760s, one of which, the Manheim Glassworks, later known as the American Flint Glass Manufactory, became the largest flint glass factory in America. Flint glass was a high-quality glass generally used for making fine tableware. Despite initial success, Stiegel went bankrupt in the mid-1770s and his glassworks ceased operations soon thereafter.

Kensington, Hub of Glassmaking

Several workers from the Manheim Glassworks eventually found employment at what came to be called the Kensington Glass Works, founded in 1771 by leather tanner Robert Towars and watchmaker Stephen Leacock. It was the first of several glass factories established in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in the area where Gunner’s Run emptied into the Delaware River. Then part of Kensington but later called Fishtown, this area would be the hub of Philadelphia glassmaking for over a century. Ownership of the Kensington Glass Works changed hands several times, and it operated only intermittently from 1777, when it closed during the Revolutionary War, through the late 1790s, when production became more regular again. Meanwhile, on the Schuylkill River, financier Robert Morris (1734–1806) and his partner John Nicholson (1757–1800) established a glassworks in the 1780s at Falls of Schuylkill (later East Falls), part of a larger industrial complex and factory town they sought to create at the site. The enterprise failed in the 1790s following the collapse of Morris and Nicholson’s other business ventures.

The Union Glass Works was another important company in Kensington’s early glassmaking hub. Established in 1826 by a group of partners from Kensington and the Boston area, the Union Glass Works grew to over one hundred workers who made blown, pressed, and cut glass. The company exhibited its products at the Franklin Institute in the late 1820s and early 1830s. Legal issues and dissension among the partners led to its closing in 1844. Another firm took over the plant in 1847 and made bottles there for many years.

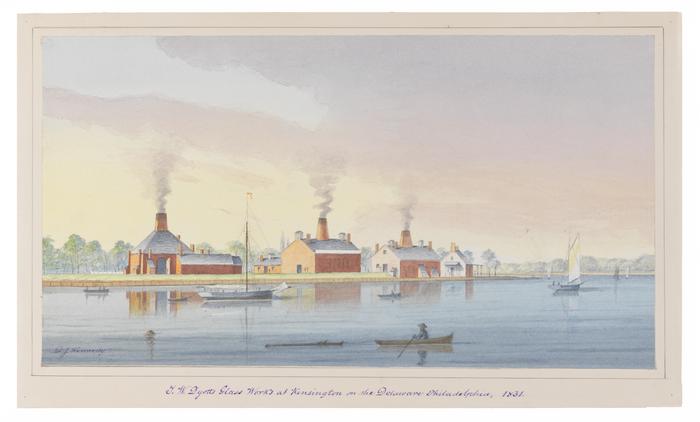

In 1816, a company headed by Kensington calico printer John Hewson (1744–1821) announced plans to build a new glassworks “on the lot adjoining the old glass works in Kensington.” The latter referred to the 1771 glass factory, which had apparently ceased operations or been converted to another use. The new factory was also called the “Kensington Glass Works.” The earlier glassworks may have been revived at some point—the historical record is unclear—but in the 1830s Thomas Dyott (1777–1861) acquired both properties and incorporated them into his Dyottville Glass Works, the nation’s largest bottle-making enterprise of the early to mid-nineteenth century.

Born in Britain, Dyott settled in Philadelphia about 1805 and became a successful maker of patent medicines, over-the-counter elixirs of dubious effectiveness that were marketed with exaggerated claims of their medicinal qualities. Patent medicines were very popular in this period and by the 1810s Dyott was selling his products in multiple states. Needing a reliable source of bottles for his medicines, Dyott invested in several glassworks in Philadelphia and New Jersey in the 1810s and 1820s, including the Kensington Glass Works, which he purchased outright in 1833. He expanded the business, renamed it the Dyottville Glass Works, and created the company town of Dyottville, a self-sufficient community based on his vision of morality, work, and clean living. Some four hundred employees worked in five glasshouses at Dyottville, which also included worker housing, a chapel, school, hospital, shops, and stores. Dyott required employees to adhere to his principles of temperance, cleanliness, exercise, and other virtuous practices. Locals called the town “Temperanceville.” Despite great initial success, Dyott went bankrupt in 1838 and spent time in prison for fraudulent business practices.

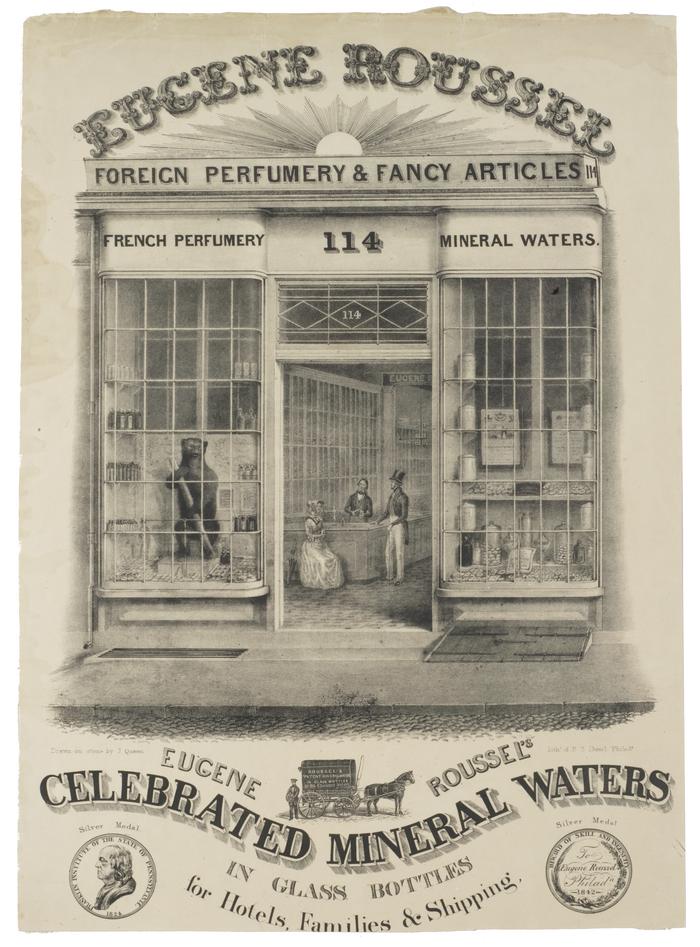

The Dyottville factories sat idle for a few years before French immigrant Eugene Roussel (1811–78) acquired them in 1842. Roussel had a perfume shop in Philadelphia in the late 1830s, from which he branched into making flavored mineral and soda waters. Largely credited with creating the American mineral water industry, Roussel’s products proved very popular and his business prospered. Like Dyott before him, Roussel purchased the Kensington/Dyottville glassworks to ensure a reliable source of bottles for his company. He sold the business in 1867, and the glassworks continued under various owners until closing around the turn of the twentieth century.

Glassworks in South Jersey

Across the river, glassmaking remained a major industry in southern New Jersey throughout the nineteenth century. Around 1817, William Coffin (d. 1844) established a glassworks with a partner in a community in Atlantic County they founded as Hammondton (later Hammonton). This was the first of eight glass works operated by Coffin and his descendants in the region over the years. Harmony Glass Works, founded in Glassboro in 1813, merged in the 1820s with the nearby Olive Glass Works, which had been started by the Stanger family in the late eighteenth century, before being acquired by the Whitney Glass Works. Operated by the Whitney family from 1838 until it closed in 1929, Whitney Glass Works was the largest and longest running of the various Glassboro manufacturers, with over a thousand workers at its peak. Dozens of other glassmakers operated in southern New Jersey in the nineteenth century as well.

In addition to Dyott, Philadelphia’s other large-scale nineteenth-century glass manufacturer was William Gillinder (1823–71), a skilled immigrant English glassmaker who in 1861 settled in Philadelphia, where he worked in area glasshouses before opening his own factory. Gillinder made a variety of products but specialized in lamps and lighting fixtures. By 1867, his company was the largest glassmaker in Philadelphia, with a workforce of two hundred at its factory in Kensington. For the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, the company, then known as Gillinder & Sons, built an elaborate working glasshouse on the festival grounds that was a very popular attraction. Gillinder & Sons opened a large plate-glass factory in Tacony in 1883, which it sold in 1887 and then purchased another glass factory in Tacony in 1901. By 1909, the company employed approximately eight hundred workers and was the largest of four glass manufacturers operating in Philadelphia.

Natural Gas Arrives in Glassmaking

Glassmaking requires intense heat and glass manufacturers often sought locations close to energy sources. Coal was the main fuel in the nineteenth century. While keeping its Philadelphia operation, Gillinder & Sons opened a plant in the coal region of southwestern Pennsylvania in 1889. The Gillinders merged the western plant with the United States Glass Company in the 1890s before selling their interest in it several years later. Natural gas replaced coal as the main energy source in the early twentieth century, and in 1912 three Gillinder brothers, grandsons of the founder, left Gillinder & Sons to operate a glassworks in Port Jervis, New York, home to rich natural gas deposits. The new company was Gillinder Brothers, separate from Gillinder & Sons in Philadelphia. The latter company abandoned its Kensington factory in 1913 and consolidated operations in Tacony, but a devastating fire in 1929 put it out of business. Gillinder Glass in Port Jervis remained in operation, however; in the late 2010s it was managed by the sixth generation of the family.

The demise in 1929 of two of the area’s largest glassworks, Gillinder in Tacony and Whitney in Glassboro, was part of an overall decline in the region’s glassmaking industry in the first half of the twentieth century. The invention of the automatic bottle machine in 1904, the relocation of large glassmakers like Gillinder to other areas, and the introduction of plastic bottles in mid-century were among the contributing factors.

However, one city—Millville, New Jersey—continued as an important glassmaking center into the twenty-first century. Pharmacist Theodore Wheaton (1852–1931) founded Wheaton Glass in Millville in 1888 to make medicine bottles. The company grew into a multinational corporation with a large local workforce that made a variety of glass products. Operating in the late 2010s as DWK Life Sciences following a series of mergers and acquisitions, it employed about two hundred workers in Millville who made laboratory products. Millville’s largest glassmaker in the early twenty-first century was Durand Glass Manufacturing Company, a tableware maker founded in 1979 that employed over a thousand workers. Its parent company, French multinational firm ARC International/Durand Glass, undertook a $40 million upgrade to the Millville facility in 2012.

Millville notwithstanding, large-scale glass manufacturing had mostly left the Philadelphia area by the early twenty-first century. Although the large glasshouses were gone, a number of small artisan glassmaking companies operated in the region, while in Millville the Glass Studio at WheatonArts, a cultural center founded by Theodore Wheaton’s grandson, continued southern New Jersey’s centuries-old glassmaking tradition.

Jack McCarthy is an archivist and historian who specializes in three areas of Philadelphia history: music, business and industry, and Northeast Philadelphia. He regularly writes, lectures, and gives tours on these subjects. His book In the Cradle of Industry and Liberty: A History of Manufacturing in Philadelphia was published in 2016 and he curated the 2017–18 exhibit Risk & Reward: Entrepreneurship and the Making of Philadelphia for the Abraham Lincoln Foundation of the Union League of Philadelphia. He serves as consulting archivist for the Philadelphia Orchestra and Mann Music Center and directs a project for Jazz Bridge entitled Documenting & Interpreting the Philly Jazz Legacy, funded by the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University