Grand Federal Procession

By Laura Rigal

Essay

Three hours long and a mile-and-a-half in length, the Grand Federal Procession was an ambitious act of political street theater, scripted by federalist supporters of the newly ratified U.S. Constitution and performed in the streets of Philadelphia on the Fourth of July 1788. From its commencement at Third and South Streets to its conclusion on Bush Hill north of the city center, the procession involved an estimated 22,000 Philadelphians: 5,000 men in the parade, with a vastly more diverse crowd of 17,000 men, women, and children watching from streets and windows, fences and roofs. Organized by rank and occupation, the marchers were roughly divided between federalist gentlemen (bankers, merchants, members of the Marine and Manufacturing Associations) and thousands of artisan-mechanics who, as the city’s producing class, were central to the ideology of federalism.

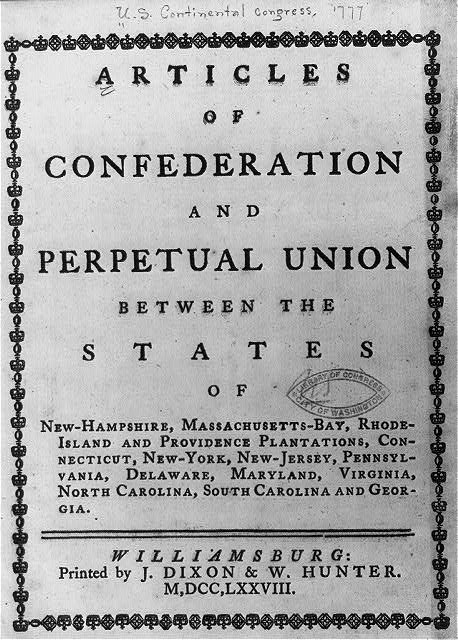

Philadelphia’s was not the first federal procession in 1788. The ceremonial template had been set in Boston (on February 8), Baltimore (May 1), and Charleston (May 27), where shipbuilding craftsmen celebrated their states’ ratifications of the Constitution with processions that put artisans at their center and featured a “Federal Ship” pulled by horses through the streets. While ratification was celebrated around the country, federal processions occurred in urban seaports where artisans had become allied with federalist merchants after years of economic adversity caused by the recession that followed the Revolution. The processions communicated an expectation shared by urban artisans and merchant-capitalists alike, that the Constitution would “lift all boats” by reviving trade and stabilizing financial instruments (such as debt financing and banking) degraded by a lethargic economy under the Articles of Confederation.

In Philadelphia, however, the goal was to seize the political and national center for the city with a “Grand” Procession on the Fourth of July that would supersede all the rest. Taking place after the Constitution had reached the necessary ratification by nine states, supporters sought to demonstrate that the national superstructure had been flat under the Articles of Confederation; the federal Union would be a “grand federal edifice,” raised from the center to more elevated and stable height. The “old boat” was unsound. A new ship of state, raised in Philadelphia’s shipyards, would succeed in global commerce.

The Order of March

The procession opened by linking federalism with colonial settlement, as twelve “axe-men” in costume clearing the road for “civilization” and for the parade itself. Federalist gentlemen followed, with silk flags marking key dates (1776, 1783, 1787) recalling the nation’s historical birth in war, accompanied by nine corps of infantry and cavalry demonstrating the police power of city troops. Then, the “Constitution” rolled into view in the form of an American eagle, thirteen feet high, pulled by six horses, with a replica of the text signed in gold by “the people.” Next came the “grand federal edifice,” or “new roof.” A neoclassical temple, thirty-six feet in height and supported by thirteen columns, it epitomized the federalist ideal of an elevated center raised by and over “the people.”

While the first half of the Grand Federal Procession featured allegorical floats and military troops, the second half was an extended pun on collective nation-making, with seventeen of some forty-five trades literally producing their respective commodities on horse-drawn stages, occasionally tossing objects (such as printed poems and baked bread) into the crowd. The joke was obvious. In a mass spectacle of American manufacturing, Philadelphia’s procession associated national assembly and political representation with the assembly and consumption of commodities. The shipbuilding crafts (mast makers, caulkers, sail makers, and carpenters) walked at the head of the trades with the Federal Ship Union, mounted with twenty guns. As the single most theatrical float of the day, the ship was noisy, inclusive, and large, with a sheet of blue canvas to simulate water and conceal wheels and machinery below. Commanding great applause, it functioned as a stage upon which a crew of twenty-five, including four young boys in costume, performed “sea ceremonies” such as “calling anchor” and “trimming sails to the wind” whenever the ship turned a street corner.

The majority of craftsmen walked in the street. Journeymen and apprentice rope makers followed masters with spinning tools (“clouts”) in hand. Coach painters carried palettes. Bricklayers marched with trowels, their flag representing a “Federal city rising” beneath a rising sun, with the motto “both buildings and rulers are the works of our hands.” Three hundred shoemakers in white aprons walked with a horse-drawn shop with six men making shoes. Hundreds of blacksmiths, tinsmiths, and nailers accompanied a working forge, drawn by nine horses, where they turned “old swords” into “plough-irons,” forged pliers, and sold nails along the route. Their motto: “By hammer in hand, all arts do stand.”

Conflicts Beneath the Surface

Despite the air of celebration, connections among American industry, settler colonialism, and state violence were never far from the surface. The United States was already fitfully at war with Shawnee, Wyandot, Delaware, and Haudenosaunee of the interior, who resisted white settler expansion beyond the Ohio River. In the Grand Federal Procession, the gunsmiths followed the biscuit bakers on a horse-drawn stage dubbed the “federal armory.” And near the end of the procession the famous armorer Daniel King (1731-1806) directed a brass-founder’s float, with furnace in full blast. King’s howitzers had helped to win the Revolutionary War, and he contributed a three-inch howitzer for firing at the procession’s closing ceremonies on Bush Hill, dubbed “Union Green.” Eventually, King howitzers would be sent to the Ohio Valley, where they furnished forts in the federalist struggle to keep Indian resistance at bay, hundreds of miles west of Philadelphia.

Details about the Grand Federal Procession come almost entirely from federalist print publicity: an “Account” by Francis Hopkinson (1737-91), chair of the organizing committee, and “Observations” by physician Benjamin Rush (1746-1813). According to Hopkinson, only six women rode in the parade, all of them on a float loaded with machinery for textile production. One unidentified woman ran the spinning jenny, while five others—the daughters and wife of calico printer John Hewson (1744-1821)—worked at “penciling a piece of very neat sprigg’d chintz of Mr Hewson’s design.” Women also provided invisible labor behind the procession. Sally Bache (1743-1808), daughter of Benjamin Franklin (1706-90), created the “flesh-coloured” costume, blue cap, sash and feather wings worn by actor John Durang (1768-1822) on the printer’s float. There, in the character of the god Mercury, he tossed copies of an ode written by Hopkinson, outlining the federalist fantasy of a global stage on which “an empire rises” before the eyes of a watching (and reading) world.

Oh for a muse of fire ! to mount

The skies,

And to a list’ning world proclaim –

Behold! Behold! An empire rise!

An era new, Time as he flies,

Hath enter’d in the book of Fame.

As a celebration of productivity the Federal Procession (like the Constitution itself) implicitly raised while sidestepping the fact of slavery. In a single, oblique reference to race, Rush cited “king cotton” and celebrated textile manufacturing as a site of national integration, uniting slave labor in the southern states with wage workers in the north. “COTTON,” Rush enthused, “may be cultivated in the southern, and manufactured in the eastern and middle states… Hence will rise a bond of union to the states, more powerful than any article of the New Constitution.”

The Constitution had been sharply contested. Pennsylvania had ratified it by a vote of only 46 to 23. By taking the streets for federalism, the Grand Federal Procession made ratification seem inevitable and popular. At parade’s end, marchers and spectators converged on the lawn of Bush Hill, the estate of William Hamilton (1745-1813) in the vicinity of Seventeenth Street and Fairmount Avenue, Philadelphia, for a citywide feast that consumed 4,000 pounds of beef, 2,600 pounds of ham, and 1,000 barrels of strong beer. In an open-air spectacle, at once solemn ceremony and mass entertainment, thousands of Philadelphians who were not actually present at the writing or ratification of the Constitution found themselves assembled as “the people,” by a grand federal act of framing, forging, and fabrication.

Laura Rigal is Associate Professor in the Departments of English and American Studies at the University of Iowa. She is the author of The American Manufactory: Art, Labor, and the World of Things in the Early Republic (Princeton University Press, 1998). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Constitution of the United States (National Archives)

- Francis Hopkinson, "An Account of the Grand Federal Procession" (Archive.org)

- Benjamin Rush, "Observations on the Fourth of July Procession in Philadelphia" (PDF, University of Wisconsin)

- "The Federal Procession of 1788," talk given by John C. Van Horne (UShistory.org)

- The Original Made in America Festival (HiddenCity Philadelphia)

- The Federalist Papers (Library of Congress)

- Federalists (UShistory.org)

- Antifederalists (UShistory.org)