Grocery Stores and Supermarkets

Essay

Local grocery stores, along with churches, elementary schools, and often saloons, have defined and anchored urban and suburban neighborhoods. General grocery stores first appeared in Philadelphia and the surrounding area in the early nineteenth century and increased in number after the Civil War as populations exploded in industrial cities like Camden and Philadelphia and their adjacent suburbs. By the end of the century, independent groceries faced increasing competition from stores operated by chains and grocers associations. Although supermarket chains never completely replaced small neighborhood grocery stores, they became typical in post-World War II suburbs. Some urban areas, meanwhile, lost their supermarkets as population declined and poverty rose. Some “food deserts” remained by the early twenty-first century, but a transformed grocery and supermarket model began to deliver nutritious food options to more Philadelphia-area residents.

In colonial times, outdoor street markets near waterfront docks provided fresh meat, fish, and produce. Such public markets, later located near railroad lines, supplied food to many town and city dwellers (and, eventually, retail grocers) into the twentieth century. In Philadelphia, a few retail stores specialized in food items, but they generally sold expensive, imported “fancy goods” such as coffee, tea, wine, sugar, and chocolate. Gradually, some of these shops began offering everyday foods as well. Butchers, bakers, dairy stores, dry goods stores (which also carried some nonperishable food items), and apothecaries (which sometimes sold spices) also sold food items.

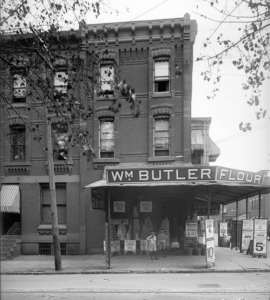

The early nineteenth century marked a transition to general groceries that carried a range of dry food items and sometimes a limited selection of longer-lasting perishables, such as potatoes and apples. In Philadelphia, hundreds of general groceries opened in both older and developing residential neighborhoods as the city expanded. DeSilver’s Philadelphia Directory and Stranger’s Guide for 1835 & 1836 listed 485 Philadelphia grocers. Some grocers operated in semi-detached and detached dwellings, depending on the neighborhood, but in Philadelphia and Camden, cities characterized by row-house blocks, most were located in row houses.

The stereotypical “corner store” offered clear retail benefits: two sidewalk facades provided extra space for displaying goods, increasing the relatively limited interior stock and display space and creating the possibility for two large plate glass display windows. However, even in this early era fewer than half of Philadelphia’s grocers, about 45 percent, had corner locations. They vied with many types of retail stores—saloons, pharmacies, dry goods, bakeries, hardware stores, and tobacconists/newsagents—all desiring visible locations. There simply were not enough corners to go around.

Challenges of Perishables

Before refrigeration, the small grocery was an especially risky business. Grocers had to estimate the quantities of foods they could sell, which could require years of experience to accurately predict the needs of a store’s particular group of customers. Many perishable goods had to be sold the same day the grocer purchased them. Overstocking, particularly of quickly perishable items, led to failure for many stores.

As the number of grocers increased, national trade publications, such as American Grocer (first published in 1869) and later Progressive Grocer (established in 1922) provided advice augmented by local and regional publications. For grocers in Philadelphia, Camden, and adjacent counties, Grocers’ Price Current (1873-86), Cash Grocer (1874-94), and Grocer (1875-90) offered price and transportation information for the region. By the end of the century, the national rail network and the appearance of nationally manufactured packaged food items reduced the need for local publications. National publications kept grocers apprised of weather conditions affecting growing seasons and reported on rail strikes or other factors that affected the quality, supply, or price of food items, which the grocer might need to explain to disappointed or even angry customers. By carrying items from an expanded marketplace, the local grocer connected each family in the neighborhood to a global food economy.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as Philadelphia transformed into the “workshop of the world” and outlying wards urbanized, the system of food distribution became increasingly complicated; at the end of the system, the neighborhood grocery made it all work. By 1920, Philadelphia had an estimated sixty-five hundred independent retail grocers and two thousand additional chain and association stores, not including delicatessens, variety stores, caterers, small shops and restaurants that sold a few groceries as a sideline, or food halls at department stores that sold primarily “fancy goods.” The number of grocery stores increased steadily through the building boom of the 1920s.

The advent of chains and grocers’ associations beginning in the 1890s increased competition in this relatively risky business, but many independent small grocers absorbed and implemented new methods. Like chain grocers, they began carrying manufactured, packaged foods, which they displayed on shelves, in glassed counters, and in complicated arrangements like pyramids. The independent grocers also continued to offer goods and services that made them indispensable to many customers. Many grocers took pride in offering homemade ethnic foods, such as German lunch meats, or homemade honey or home-smoked hams. Neighborhood grocery stores also offered an extension of family domestic space as women and children ran in and out every day, even several times a day, before most families acquired electric refrigerators.

By the early years of the twentieth century, independent grocers had to show they were keeping up with modern methods as a defense against criticisms by some Progressive reformers. Journalist Ida Tarbell (1857-1944), for instance, suggested that in addition to being tempted to overweigh goods, independent grocers might sell unpackaged goods that could be contaminated or adulterated. For this reason, professional trade publications suggested displaying packaged and branded foods in large storefront windows, which also allowed passersby a full view of the interior of the store.

Chains and Supermarkets

The first grocery store chains in Philadelphia, established by several Scots-Irish and British immigrants, emerged in the 1890s. By 1910 they accounted for about 490 stores, including the Acme Tea Company with two hundred stores and Robinson and Crawford, first established in South Philadelphia, with about one hundred. Originally very similar to independent groceries in size and daily operation, stores within a chain system benefited from central management of inventory.

Chains practiced economies of scale unavailable to independent grocers. By standardizing inventories of member stores, they could purchase large quantities at discount from wholesalers and pass on lower prices to customers. A Wharton School economist, Clyde Lyndon King (1879-1937), suggested, though, that chains actually lowered their prices to points only just below those of independent grocers. The largest chains skipped the wholesalers and dealt directly with food manufacturers and sometimes even with farmers.

To compete with these chains (and the growing number of independents), by the 1890s some retail grocers joined together to form wholesale associations. Reformers noted these retail cooperatives were especially successful in Philadelphia. The Retail Grocers’ Association (Girard Grocery Company) included about seven hundred Triangle Stores, so-called because their newspaper advertisements featured a triangular emblem. The other significant grocery association in Philadelphia was the Unity-Frankford Association (Frankford Grocery Company). By 1920, about twenty-two hundred grocers had joined one or the other. Smaller groups of grocers had less success. A group of thirty Polish grocers started the Richmond Grocery Company, but they did not have adequate working capital to purchase the large quantities necessary to pass on competitive lower prices to customers. Their association folded after just a few years.

Grocers, as well as customers, struggled with the increasing price of food. Like reformers, grocers identified the various middlemen in the food distribution process as a cause of rising food prices. As retailers joined together in wholesale cooperatives, wholesalers fought back by creating retail cooperatives. Food prices fluctuated wildly and became an issue in the 1912 election. The years 1916-17 saw a steep rise in prices of many goods, including the daily staples of flour and potatoes; women in several districts of the city, primarily in South Philadelphia, attacked pushcart vendors and grocers. A mayoral commission appointed to investigate found that prices varied widely from grocer to grocer and that independent grocers invariably charged more than chain stores.

Chain-Store Efficiencies

Progressive reformers approved of the large-scale efficiency of the chain stores and attacked the independent retail grocer as the main culprit in high food prices. In Philadelphia, important avenues devoted to small retail stores (Frankford Avenue, Germantown Avenue, Ridge Avenue, Woodland Avenue) frequently had two or three grocery stores to a block. In many areas of the city, two of four corners at an intersection were occupied by grocery stores. By World War I, the city had one retail grocery for every fifty-nine families or 295 people. Experts estimated this allowed the average grocer an income of $640 or less after expenses. Reformers believed cooperative associations should regulate the grocery trade by imposing stricter credit requirements on grocers, reducing both competition and failure.

Even the chains had difficulty competing effectively. During and after World War I, they began merging with each other. When the Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company, the first grocery store chain in the nation, entered Philadelphia from New York and New Jersey, local mergers followed. Five Philadelphia chains, including the Acme Tea Company, combined to create the American Stores Company, parent of ACME Markets. By 1920, six hundred grocers in the city and another six hundred in the surrounding counties had become part of American Stores. ACME experimented in New Jersey with two self-serve supermarkets, but both ACME and A&P were reluctant to abandon the familiar and overall successful model of the neighborhood grocery.

From the mid-1920s to the mid-1930s, automobile and refrigerator ownership, the latter of which increased tenfold, changed the way Americans shopped for food. The Great Depression of the 1930s made customers even more sensitive to food prices and that decade saw a wave of supermarket expansion and innovation. Three local businessmen founded the Penn Fruit Produce Store (1927-78) as a green grocery (only produce), but they quickly transformed their stores into a full general groceries in response to competition from ACME and A&P. By the late 1930s, Penn Fruit operated six self-serve supermarkets in Philadelphia. At its height in the 1950s, Penn Fruit ranked as one of the most successful supermarket chains in the United States.

The Depression also provided the impetus for grocery and supermarket modernization. New Deal Main Street Programs encouraged even small businesses to remodel in a Moderne style characterized by glass and chrome, and newly constructed supermarkets most fully exploited the new visual taste. Most iconically, Penn Fruit became known for its modern streamlined curving arched storefront, even more so in 1955 when the company hired commercial architect Victor Gruen (1903-80) to create a prototype store design for the Black Horse Shopping Center in Audubon, New Jersey. By the 1950s, developers looked to supermarkets as anchor stores for new suburban shopping centers reached by automobile. In 1953, Penn Fruit opened the first store in Shop-a-Rama in Levittown, Bucks County. Food Fair, which originated Harrisburg in the 1920s, soon followed. Compared to these large, well-lit, glass and chrome structures in colorful new shopping centers surrounding by parking lots, traditional corner groceries in cities and the small shopping districts of inner suburbs like Swarthmore and Drexel Hill, Delaware County, often seemed out of date, unhygienic, and simply inconvenient.

Suburban Migration

In the mid- to late-twentieth century, supermarkets were identified with suburbia. Giant, which began as a small meat market in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, expanded to several cities, but after World War II the company followed families moving to the suburbs. Genuardi’s, which began as a green grocery in Norristown in the 1920s and evolved into a supermarket by the 1950s, expanded in the suburban counties west and north of Philadelphia but never opened a store in the city.

By 1970, supermarkets, which had revolutionized food distribution by carrying all kinds of foods under one roof and had largely stabilized food prices, accounted for about 70 percent of national food sales. Still, competition emerged. Offering an alternative to congested parking lots and long check-out lines, new “convenience” stores with easily accessible, roadside locations stocked basic items such as milk, snacks, and ready-made foods, tobacco products, newspapers, and sundries. In the 1990s, many began installing automatic-teller machines. Convenience stores generally charged higher prices than grocery stores and supermarkets, but they offered longer hours, sometimes twenty-four hours a day, and relatively quick service.

As with supermarkets, local and regional convenience stores competed with national chains. A decline in popularity of home-delivered milk led two of the region’s dairy producers into the convenience store business: Heritage’s Dairy Stores, familiar in Camden and other southern New Jersey counties, opened its first convenience store in Westville, New Jersey, in 1957. In Pennsylvania, the first Wawa Food Market opened in Folsom, Delaware County, in 1964. Wawa expanded into New Jersey in 1968 and just one year later into Delaware. In the early twenty-first century, Wawa also opened Center City Philadelphia stores geared toward urban pedestrians. Wawa and Heritage’s competed with the national 7-Eleven chain, founded in Texas in the 1920s, which became more famous for its Slurpee and large-sized sugared drinks than for milk and daily basics.

Large discount stores, such as Walmart and Target, also competed with supermarkets. With grocery departments as just one of their many offerings, these stores successfully offered one-stop shopping. Price clubs, like BJs and COSTCO, offered even more inexpensive food items for those who could pay annual memberships and buy in larger than usual quantities.

Food Deserts and Obesity

By the 1990s, the Philadelphia region had a full complement of supermarkets, including Giant, Shop Rite, IGA, Trader Joe’s, and Whole Foods (joined in the twenty-first century by Aldi, which sold discount organic produce). Quality and prices varied significantly between supermarkets and between neighborhoods, as new food categories—organic, non-GMO, and gluten-free—came into demand, for health or political reasons. As “foodies” sought tasteful and unusual ingredients, supermarkets competed with farmers’ markets for customers who sought to “buy local.”

At the same time, in the 1990s several studies indicated that Philadelphia residents exhibited increasing levels of obesity, diabetes, and other diseases closely related to poor nutrition. This once again made small, independent grocery stores the target of critics. Most neighborhood grocery stores still carried mainly packaged processed foods, with limited produce, meat, and seafood selection. Some urban areas (sections of Germantown, for instance, and the city of Camden) had deteriorated into “food deserts,” defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as areas lacking relatively easy access to the ingredients for a healthy diet, such as affordable fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low fat milk, and other fresh food products.

To combat the high incidence of diet-related diseases in low-income neighborhoods, in 1992 Duane Perry (b. 1955), then-executive director of the Reading Terminal Market Merchants’ Association, founded the Food Trust to encourage public-sector support of a nutritious food supply and a return of supermarkets to lower-income neighborhoods. Because more Philadelphians had convenient access to small neighborhood groceries, the Philadelphia Department of Public Health launched the Get Healthy Philadelphia initiative and offered neighborhood grocers financial incentive to carry at least two healthy food items in at least two food categories. In Camden, the situation was less promising as plans for a second full-service supermarket, a new ShopRite, fell through in 2016. Earlier, the city lacked a full-service supermarket for one year until a PriceRite opened in 2014, the first new supermarket to enter the city since the late 1960s.

Due to increasing publicity, dedicated activists, and widespread health concerns, supermarkets and neighborhood grocery stores brought an improved selection of healthy foods to many of Philadelphia’s residents by the beginning of the twenty-first century. Despite new forms of competition, the corner grocery—the original convenience store—survived, and the distinctive offerings of Mexican, Asian, Italian, Nigerian, and other ethnic grocery stores in the city’s neighborhoods continued to attract a loyal following.

Anne Krulikowski holds a Ph.D. in American History with a concentration in material culture/historic preservation from the University of Delaware. She teaches at West Chester University and has published articles on working-class neighborhoods, oral history, vernacular architecture, and grocery stores. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Mapping: Grocery and convenience stores in Pa. where you can buy beer (and soon, wine!) (WHYY, June 16. 2016)

- Turning chores into classrooms: New grocery store experiment hopes to inspire learning (WHYY, September 10, 2018)

- Will Philly’s parking wars cost Mount Airy a new grocery store? (WHYY, September 14, 2018)

- Grocery stores are popping up in Philadelphia. Don’t be fooled, the boom is over (WHYY, September 19, 2018)