Scots Irish (Scotch Irish)

Essay

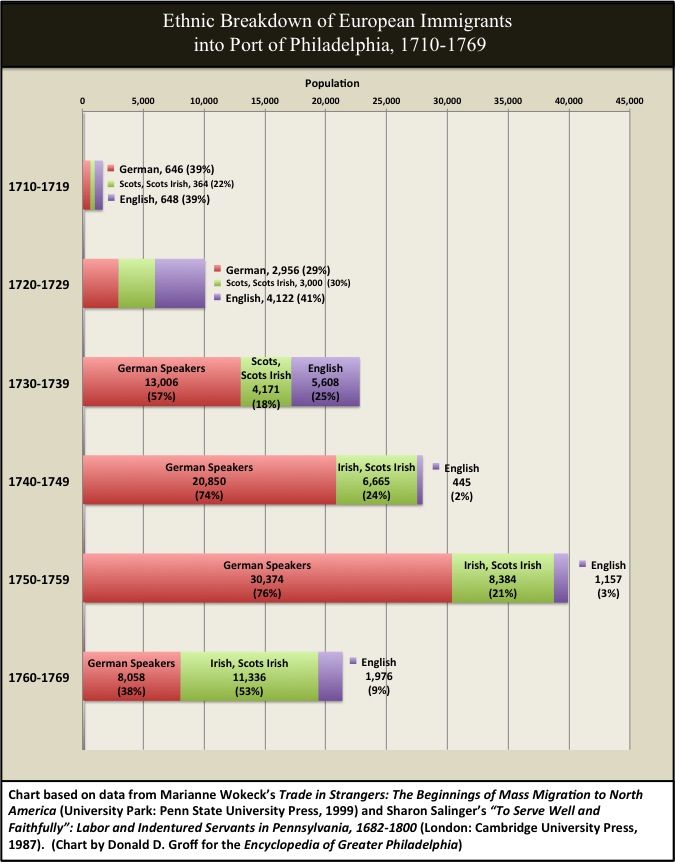

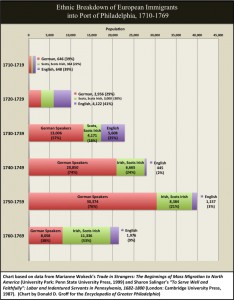

Pennsylvania’s Scots Irish, a hybrid people of Scots and Irish ancestry, were the most numerically predominant group within an Irish diaspora migration that brought between 250,000 and 500,000 Irish immigrants (most of them Protestants from Ulster and predominately Presbyterians) to America between 1700 and 1820. Philadelphia was one of their principal destinations.

As the prototypical “peoples in motion” of their time, the Scots Irish moved first from the Scottish Lowlands to Ulster during the seventeenth century at the behest of the English, who desired them to act as a Protestant colonizing force among Ireland’s native Catholics. After 1700, when faced with deteriorating economic conditions and mounting religious and political persecution as dissenting Protestants (not members of the official, state-sponsored Church of Ireland) in Ireland, and later, after the failed 1798 Uprising (a rebellion of Irish Protestants and Catholics that aimed to overthrow British rule and establish a republic) and the British crackdown that followed it, they chose to migrate again.

This time, the Scots Irish came to America, migrating as servants and free people, individuals and families, and sometimes as political exiles and refugees. They arrived in two major waves at the ports of New Castle, Delaware, and Philadelphia between 1710 and 1776 and then again between 1780 and 1820. After nearly a century of migration, the Scots Irish became one of the largest non-English ethnic groups in Pennsylvania, composing approximately 25 percent of Philadelphia’s population and 15 percent of the state’s population in 1790; they were also among the most influential.

Cradle of Scots Irish Culture

The Mid-Atlantic, particularly Pennsylvania, was thus the first American home of the Scots Irish, serving as the cradle for their culture. Pennsylvania had much to offer them. Because of the value proprietor William Penn (1644–1718) had placed on religious tolerance in planning his colony, Pennsylvania had a pluralistic society where these Scots Irish Presbyterians would no longer be stigmatized as dissenters. The colony’s economy, anchored by the rapidly expanding port city of Philadelphia, was also growing rapidly. An expanding flaxseed trade with Ireland during the eighteenth century, one closely tied to the immigrant trade, offered immigrant Scots Irish merchants abundant commercial opportunities in Philadelphia and encouraged farm families to continue the linen production they had done in Ireland in America. The growing colony and its practice of purchasing lands from Indians also offered newcomers abundant rural lands and a generally peaceful climate in which to settle. Finally, with Philadelphia as the headquarters of the Presbyterian Church in America, the Delaware Valley also offered Scots Irish Presbyterians the promise of a spiritual home.

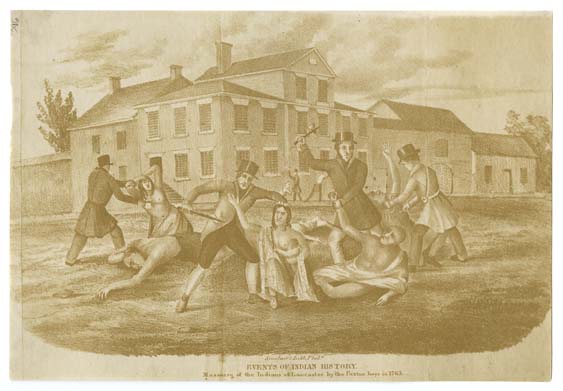

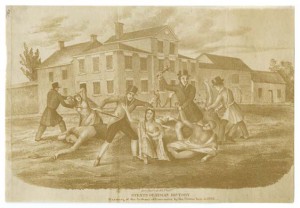

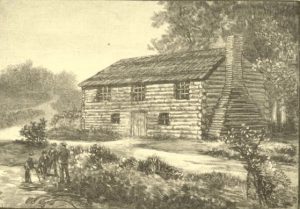

Popular histories of Pennsylvania’s Scots Irish associate them mostly with the expansion of the colonial frontier, where, as prototypical American backwoodsmen, they built log cabins, farmed and traded, wove flax into linen, distilled whiskey, and fought Native Americans. Because of their participation in the notorious Paxton Boys’ “massacre” of the Christianized Conestoga Indians at Lancaster (1763) and their eagerness to fight brutally against Native American, French, and British enemies during first the Seven Years’ War (1756–63) and then the American Revolution (1776–83), scholars have often portrayed them as violent Indian-haters and frontier ruffians. Their violent resistance against the whiskey tax during the Whiskey Rebellion (1794) and their especially vicious destruction of Philadelphia’s Catholic Irish immigrant neighborhoods during the city’s “Bible riots” (1844) not only confirmed their reputed predilection for violence, but ensured that historians would regard them as racists and nativists, too.

Yet these stereotyped and negative images are only partly correct. In actuality, Pennsylvania’s Scots Irish were a socioeconomically diverse immigrant group from a variety of class, occupational, and educational backgrounds. While many did settle on the Pennsylvania frontier, many others did not; not all Scots Irish were country bumpkins and gun-toting ruffians. Many Scots Irish individuals and families, who ranged in status from impoverished indentured servants, to middling shopkeepers and traders, to wealthy Atlantic World merchants and professional men, made their homes in urban Philadelphia and its hinterlands and in other, smaller interior Pennsylvania towns such as Carlisle, Easton, Bedford, and Pittsburgh. They did not farm, but traded, retailed goods or services, practiced professions or trades, or labored as servants. And while some did live in log cabins, many others resided in stylish stone and brick homes where they enjoyed the kind of cosmopolitan lifestyle that other elite Americans did, albeit with a Scot-Irish emphasis on family, church, and education.

Positive Contributions

Pennsylvania’s Scots Irish thus contributed to the Philadelphia region in many positive ways, including by shaping the religious landscape. Having suffered as dissenters in Ulster, Scots Irish Presbyterians relished Pennsylvania’s commitment to religious pluralism. When the Ulster-born minister Francis Makemie (1658–1708) founded the first presbytery in the colonies at Philadelphia in 1706, Presbyterians claimed the Delaware Valley as their own. The establishment of their first American synod at Philadelphia and the creation of new presbyteries at New Castle, Delaware, and Long Island, New York, cemented these regional ties in 1717. The Presbyterian presence in the region grew quickly thereafter, with new congregations and meetinghouses closely following the founding of Scots Irish settlements near Philadelphia and in the colony’s growing backcountry. The church’s influence continued into the twenty-first century, as the Synod of the Trinity (formerly the Synod of Philadelphia) remained one of the largest synods in the church.

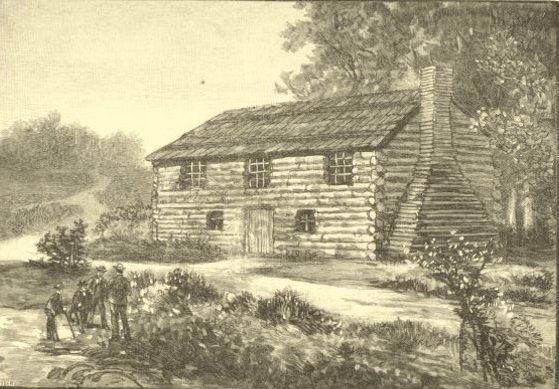

Scots Irish Presbyterians also had a profound impact on higher education in the region. When the transatlantic religious revival known as the Great Awakening (approximately 1730–60) bitterly split Scots Irish Presbyterians into New Sides who favored conversion and Old Sides who adhered to the primacy of scripture, it heightened Presbyterian commitments to education. New Side Presbyterian evangelicals such as the Ulster-born Rev. William Tennent (1673-1746) bolstered their influence by founding schools to train evangelically minded, converted clergy. The success of Tennent’s boys’ academy (derisively called the “Log College” by critics), which he founded at Neshaminy, Bucks County, in 1726, helped set the stage for the 1746 chartering of the College of New Jersey (Princeton University). Old Side Presbyterians responded by founding their own schools. The Ulster-born Rev. Francis Alison (1705-79) established his New London Academy in 1743 in Chester County (it was later moved to Newark, Delaware, and evolved into the University of Delaware) and served as vice provost at the College of Philadelphia (University of Pennsylvania) until his death in 1779. Later, long after the church repaired this schism and reunited, Benjamin Rush and a group of Old Side Presbyterians chartered Dickinson College in Carlisle in 1783. Presbyterians also founded Arcadia, Wilson, Waynesburg, and Westminster Colleges.

Leadership Positions

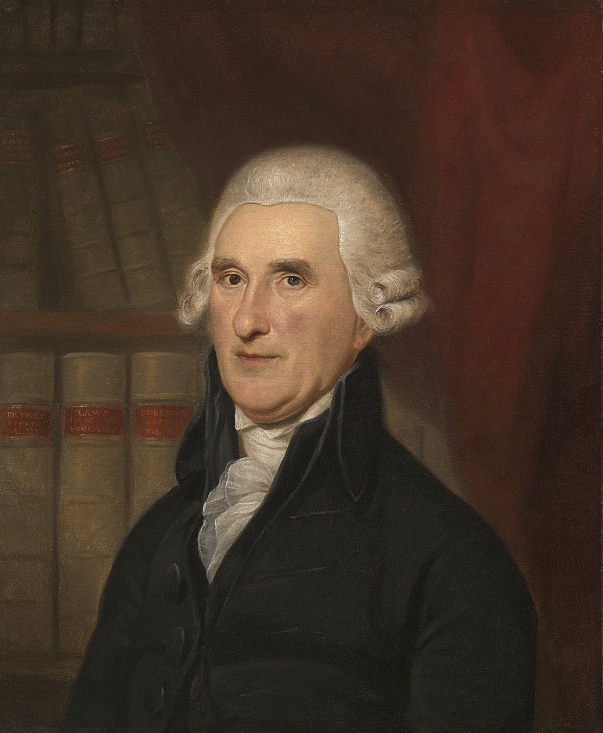

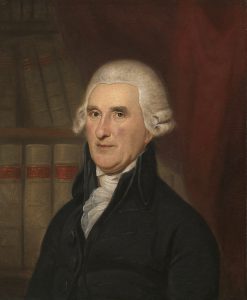

In politics, the Scots Irish held many critical political leadership positions in the state. Having experienced discrimination under British penal laws in Ireland, the Scots Irish formed the core of the commonwealth’s revolutionary vanguard by leading the resistance movement to Great Britain and volunteering in large numbers for Continental army and militia service. As committed republicans, they drafted a radical state constitution that democratized the new state’s republican political order by establishing a unicameral legislative government. Although that government model lasted only until 1790, it was the most radical state government of the revolutionary period. Scots Irish political participation continued during the early republic when they strengthened their control of state politics with the election of one of their own, the Chester County–born attorney and state Supreme Court Justice Thomas McKean (1734–1817) as the state’s Democratic-Republican governor (1799–1808).

Despite such gains, Scots Irish influence gradually waned during the nineteenth century. This happened in part because the new waves of more predominately Irish Catholic immigrants who began to arrive after 1815, and especially during the famine migrations of the late 1840s and 1850s, challenged what it meant to be Irish in America. The Scots Irish, who could claim a heritage as proud patriots and republicans during the Revolution and its aftermath, reacted defensively by aligning themselves with America’s white, Protestant, and sometimes xenophobic cultural mainstream. Some of their working-class members took to the streets to join other nativists in violent anti-Catholic riots, and they supported the anti-immigrant platform of the Know-Nothing Party during the 1850s. Others acted in less confrontational ways to shed their identity as “Irish,” the label they had long accepted, and to adopt the name “Scotch Irish” as a way to highlight their Scots Protestant heritage, a testament to their status as white American pioneers of the nation. To reinforce their claims as pioneers and weave themselves into the fabric of the nation’s founding, they established organizations such as the Pennsylvania Scotch Irish Society (1889) to preserve their history, “keep alive the spirit de corps of the Scotch Irish people,” and promote their unique contributions to American culture.

Scots Irish influence in the region also dwindled because this “people in motion” continued to move. While some stayed in Pennsylvania, many other families left the region in search of new opportunities elsewhere beginning in the eighteenth century. At first, they followed the Great Wagon Road into the southern backcountries of Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia. Later, they traveled other overland routes across the Appalachian Mountains to pioneer the American Midwest and states such as Kentucky and Tennessee. In moving, they created a “Greater Pennsylvania” culture region that extended Scots Irish influence well beyond the state’s borders, while simultaneously putting a Scots Irish stamp on southern backcountry and Appalachian culture. It is no surprise, then, that according to U.S. Census data from 2015, only 1.1 percent of Pennsylvania’s residents claimed Scots Irish ancestry by the early decades of the twenty-first century. Thanks to several centuries of migration, Scots Irish had become more often associated with the hillbilly culture of southern Appalachia or the cracker culture of the Deep South than with the mid-Atlantic region.

Judith Ridner is an associate professor of history at Mississippi State University. She is the author of A Town In-Between: Carlisle, Pennsylvania and the Early Mid-Atlantic Interior (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010) and The Scots Irish of Early Pennsylvania (to be published in 2017 by Temple University Press for the Pennsylvania Historical Association). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- The Scotch Irish Society of the USA

- Digital Paxton (Library Company of Philadelphia)

- Resources about the "Philadelphia Riots" from Villanova Digital Collections (Falvey Memorial Library, Villanova University)

- Presbyterian Historical Society Digital Collection

- Thomas McKean (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)