Gross Clinic (The)

Essay

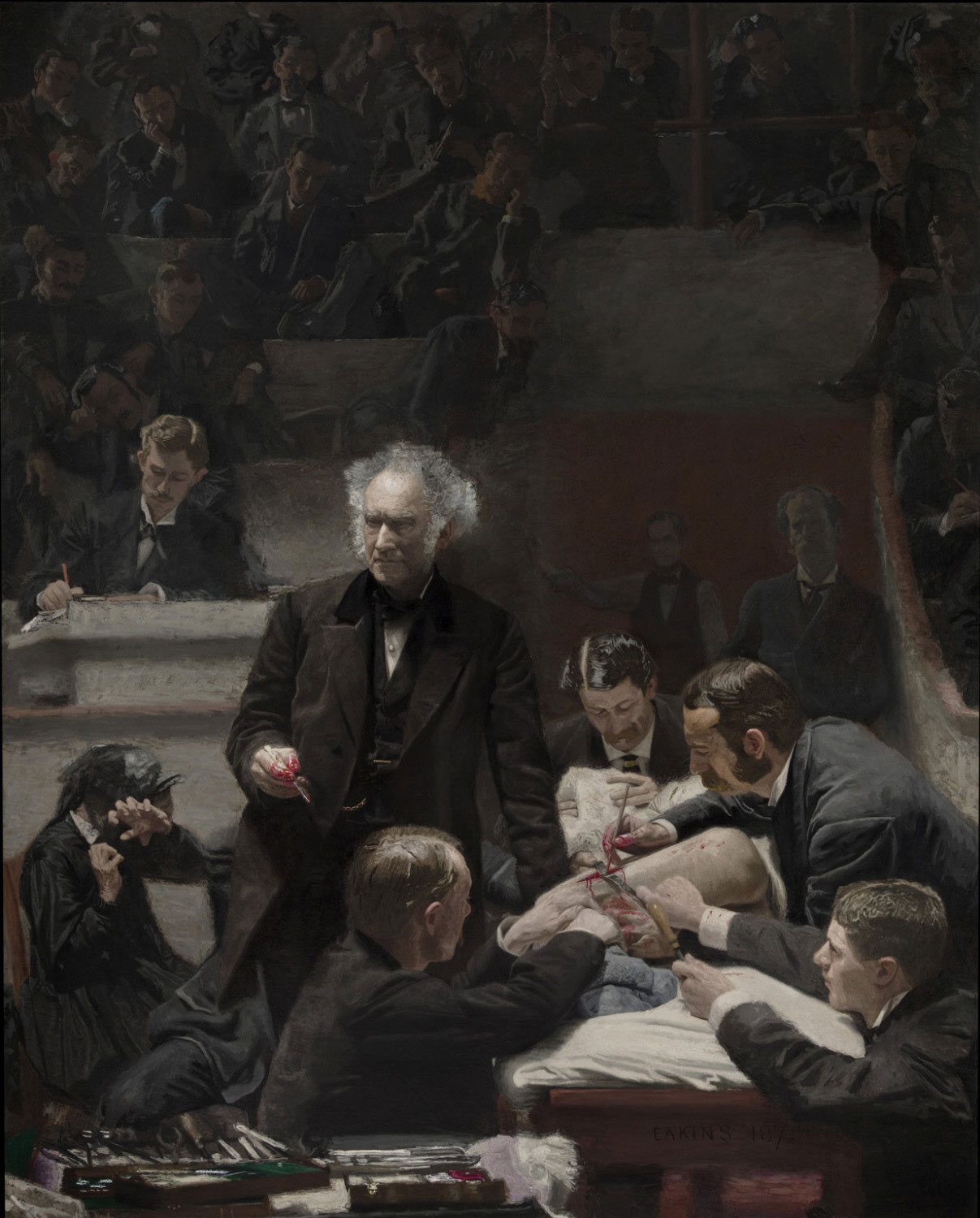

The Gross Clinic, painted in 1875 by Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), is among the most highly regarded American artworks from the nineteenth century. It is a portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (1805-84), an internationally celebrated surgeon who taught at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia from 1856 to 1882. Created by a local artist and depicting a famous local doctor, the monumental painting bears a special connection to Philadelphia.

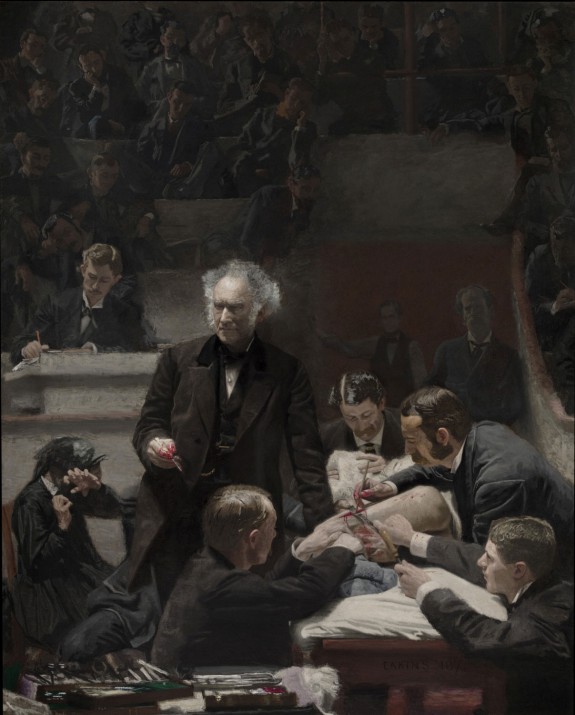

The portrait shows Dr. Gross conducting an innovative medical procedure: a surgery to remove infected bone from his patient’s thigh. It is an intense scene with many participants. To the right, five young doctors attend to the patient. While W. Joseph Hearn (1842-1917) applies a sedating chloroform compress to the patient’s face, Charles S. Briggs (1851-1920) stabilizes the small body. Daniel Appel (1854-1914) and an unidentifiable doctor hidden behind Dr. Gross pull back the patient’s flesh, while James M. Barton (1846-?) clears blood from the site of the incision. To the left, a seated woman, possibly the patient’s mother, turns away from the scene and shields her face in horror. At a lectern above the operating area, Dr. Franklin West (1851-77) takes notes for the medical record. In the background, in shadow, medical students and other onlookers observe the scene–some with intrigue and some with boredom. Eakins watches from the audience, too. He sits pencil-in-hand, cropped by the right edge of the canvas. Near the center of the image Dr. Gross, lit from above, pauses as he looks away from the surgery while holding a bloody scalpel in his hand. Dramatic lighting, thoughtful composition, masterful modeling of tones, and confident brushwork heighten the potency of the image.

Scholars have connected this scene to historical depictions of anatomy lessons including The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Velpeau (1864), by F.N.A. Feyen-Perrin (1829-88). Unlike Feyen-Perrin’s painting, which shows doctors dissecting a cadaver, Eakins’s work notably presents a doctor performing limb-saving surgery on a living patient. This distinction would not have been lost on Eakins, who was interested in science, medicine, and technology, and who painted portraits of leaders in those fields. He additionally studied anatomy, observed surgeries, and used photography in his art practice to better understand the human body and enhance the realism of his paintings.

Exhibition and Critical Reception

Eakins painted The Gross Clinic as a submission for the Centennial Exhibition, the world’s fair that Philadelphia hosted in 1876. Philadelphia led the nation in medical innovation and practice during the nineteenth century, so an expertly painted portrait of the city’s most famous living surgeon at work could have excellently showcased Philadelphia’s local achievements and national significance at the fair. Jury members rejected the painting from the fine arts exhibition, however, because they found the scene too disturbing. The Gross Clinic was displayed instead among other medicine-themed items in the U.S. Army Post Hospital exhibit.

Critics initially responded to the painting with mixed reactions. Some praised Eakins’s ability to render figures, although they deemed his depiction of the patient too visually confusing. Viewers frequently noted the way Eakins captured the drama of surgery, but they found the painting’s goriness distasteful. In 1878 the Jefferson alumni association purchased the painting for $200. The artwork was exhibited nationally three times in the next two decades, but it did not receive widespread praise until writers championed it in memorial catalogues published shortly after Eakins’s death in 1916.

In the years since, scholars have interpreted the painting in a number of ways. Focusing on Dr. Gross and the history of medicine in Philadelphia, the painting is a heroic portrait of a leader in the field of surgery. Interpreted through the lens of psychoanalysis, the painting provides an anxious commentary on the relationship between painting and writing in the nineteenth century. Analyses of the ambiguously gendered patient and the changing critical reception of the painting have offered insight into nineteenth-century ideas about gender and sexuality. The painting is discussed most frequently as an icon of American art. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries it made a strong case that American painting could be as sophisticated as any European artwork.

Twenty-first Century Significance

For over a century the painting’s main home was at Jefferson, where it was a fixture for students and faculty. The Gross Clinic became the subject of expanded public interest in November 2006, when the school announced plans to sell the painting to raise funds for new medical and education facilities. The Crystal Bridges Museum in Bentonville, Arkansas, in collaboration with the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., offered to purchase the painting for $68 million. The arrangement stipulated that a local organization could buy the painting instead if it could match the agreed-upon price within the short period of forty-five days.

Almost immediately, a local grassroots effort to keep the painting in the city emerged. Soon after, several Philadelphia institutions collaborated to launch a major fund-raising campaign to enable the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts to jointly purchase the painting. Leaders of these movements argued that The Gross Clinic was a Philadelphia icon that needed to remain in the city with which it was most strongly affiliated. Local media outlets provided educational information about the painting and daily updates on the fundraising effort, while area residents and other concerned individuals wrote countless blog posts and letters to the editor to share their feelings about the artwork. Taken together, these activities propelled a swell of civic pride. A desire to defend Philadelphia’s reputation and assert its role as a significant cultural center fueled the fervor for protecting this piece of the city’s cultural heritage. Over 3,600 individuals donated money in support of the effort. The museum and the academy raised additional funds by selling objects deemed less central to their collections. In 2007 the two institutions jointly purchased The Gross Clinic, made plans to exhibit it at each location on a rotating basis, and enabled a local icon to remain in Philadelphia.

Laura Holzman is Assistant Professor of Art History and Museum Studies at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. Research assistant Catherine Harmon aided in determining lifespan dates for individuals depicted in the painting. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University