Mansions

Essay

Since the earliest European settlement in the seventeenth century, but especially from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries, large houses constructed by elites in the Philadelphia region provided agreeable places to live that demonstrated social status. As architectural fashion and geographic distribution changed, mansions served as conspicuous symbols for elite Philadelphians and were a salient element of the city’s urban fabric, its surrounding countryside, and ultimately suburban estates. As prominent features of Philadelphia’s built landscape, in the late twentieth century mansions reflected the city’s relative decline. Preservation efforts directed at salvaging these buildings had the dual function of protecting the region’s material history while also, intentionally and unintentionally, reinforcing a version of history that emphasized its wealthy, white, elite, and patriarchal character. As a result, mansions, which have defined the Philadelphia area’s social, economic, political, and cultural life, became vital to the way the region thinks about its past, present, and future.

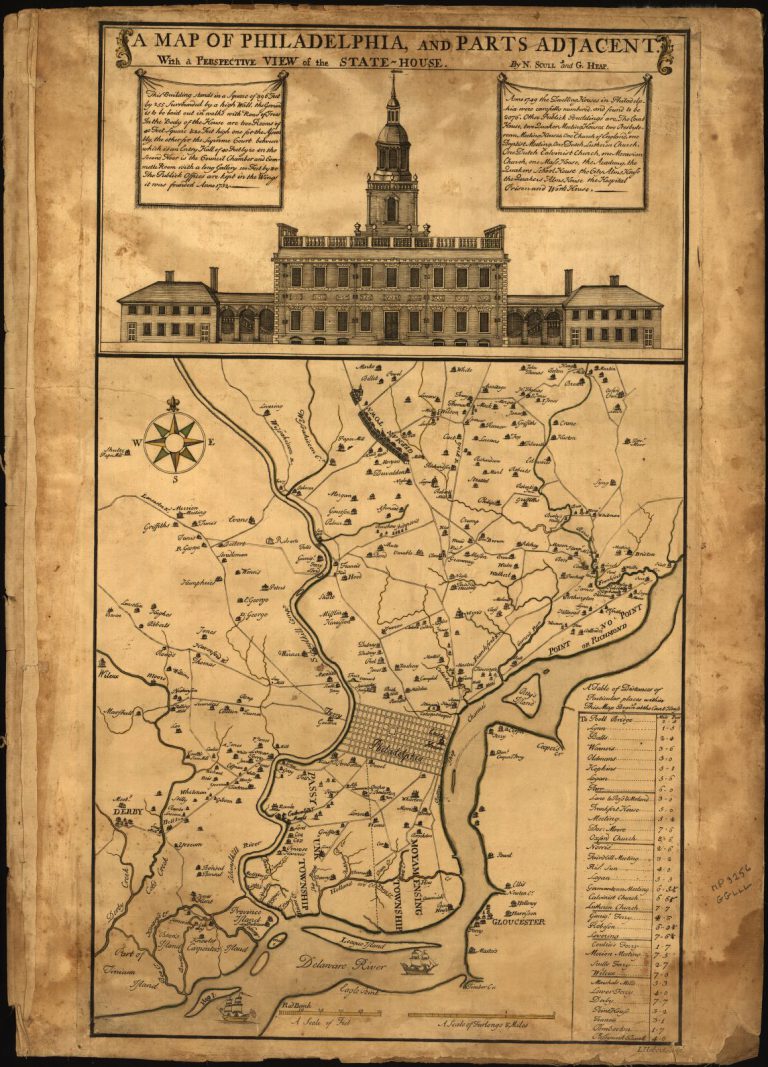

Mansions have served as town and country housing for some of the region’s leading families for several centuries, helping to define architectural style, construct social life, and structure commercial and political practices. Pennsbury Manor, constructed for William Penn (1644–1718) along the Delaware River about twenty-five miles north of Philadelphia, provided the earliest effort to recreate English genteel life. Other well-to-do Philadelphians followed suit, building houses in the city and its surrounding countryside. The map by Nicholas Scull (1687–1761) and George Heap (1714–52), originally published in 1752, noted the location of “the most Remarkable Places” in and around Philadelphia, including many houses later termed mansions. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these mansions clustered along the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers above the city of Philadelphia. Construction of mansions therefore took place in close proximity to Philadelphia, highlighting the importance of town-centered activities such as trade and commerce to many of the region’s colonial elites. At the same time, their rural location away from the built-up area of early Philadelphia provided what was thought to be a healthier setting.

Mansions have also always been a significant feature of Philadelphia’s urban fabric. From the origins of the city, leading citizens erected mansions. A noteworthy example was the Slate Roof house built for Samuel Carpenter (1649–1714) on Second Street (1687, demolished 1867), which William Penn lived in for a time. Before the American Revolution, figures such as Samuel Powel (1738–93), the last mayor of Philadelphia under British rule, constructed large brick townhouses that functioned as dwellings. Their plain exteriors often belied elaborate interiors. An important mansion built by financier Robert Morris (1734–1806) and lived in by Presidents George Washington (1732–99) and John Adams (1735–1826), was the President’s House (1767–69, demolished 1832), which became a focal point for battles about historical interpretation in the early twenty-first century because it was also the site of Washington’s slave quarters. After the Revolution, mansions like that built for merchant, banker, and senator William Bingham (1752–1804), depicted in a view by William Birch (1755–1834) (q.v., 1789, demolished about 1850), highlighted new taste in architecture as well as the wealth of the new nation. Some townhouses swiftly made a transition from mansion to institutional use, such as the house at Thirteenth and Walnut Street designed for Thomas Butler (1778–1838). Not quite completed by the time of his death, by 1850 it had been acquired by the Philadelphia Club, serving as a familiar “home away from home” for the region’s elites, many of whom were beginning to own countrified suburban houses.

The Mansion Boom

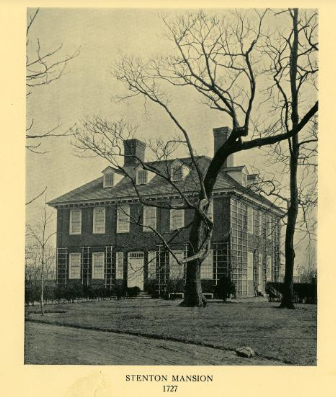

Early country houses could be architecturally somewhat unrefined. Fountain Low (later Graeme Park), built for Sir William Keith (1669–1749) in the 1720s, for example, was noted more for its setting and landscape than its architecture. More distinguished and in keeping with transatlantic trends in building compact classical houses for professional and merchant elites was Stenton (1723–30), the country estate of James Logan (1674–1751) near Germantown. The Penn family remained influential in mansion building until the American Revolution: William Penn’s sons constructed their own houses and influenced others to build, as at Bush Hill (built 1740, demolished 1875) and Belmont (1742–50). A boom in mansion building occurred as Philadelphia became the largest and most important North American city before the Revolution, typified by the elegant Palladian mansion Mount Pleasant (1761–62) and the house of Pennsylvania Chief Justice Benjamin Chew (1722–1810) at Cliveden near Germantown (1763–67). The Chew mansion later served as a British fortress during the 1777 Battle of Germantown. Although large by colonial standards, in the wider British world before 1775 these mansions were considered modest in size, appealing particularly to upper-middle-class genteel families who comprised the colonial gentry.

Noteworthy country estates built after the Revolution included The Woodlands (built c. 1770, renovated in neoclassical style 1786–89), redesigned by William Hamilton (1745–1813), and Lemon Hill (1799–1801), the estate of merchant Henry Pratt (1761–1838). Andalusia, built in 1795 and remodeled by owner Nicholas Biddle (1786–1844) and architect Thomas U. Walter (1804–87) in the mid-1830s, exemplified the popular Greek Revival style, while George Read II (1765–1836) in New Castle, Delaware, built his mansion (1797–1804) in the new Federal style. Architectural inspiration came from even further afield, as in the case of Point Breeze near Bordentown, New Jersey (1820s, demolished 1850), the mansion of Frenchman Joseph Bonaparte (1768–1844). At least one Philadelphian, diarist Sydney George Fisher, thought some mansions too ornate. Of Phil-Ellena in Mount Airy, called the “largest of America’s Greek Revival palaces,” Fisher wrote, “It would not be easy to find anywhere ignorance, pretension, bad taste, and wealth more forcibly expressed.”

As complex social organisms, mansions hosted numerous inhabitants. Houses and estates supported not only those who built and lived in them, but they also required labor to sustain them. Workforces at pre-Revolutionary mansions often comprised a mix of free labor, indentured servants, and enslaved Africans. Later, waves of immigrants provided much of the labor needed to run and maintain these large and complex houses. Mansions symbolized power and status in material ways; the hierarchical social structure of their inhabitants also reinforced these messages.

Urban Townhouse Mansions

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Philadelphia’s most noteworthy architects designed mansions for the city’s rising bourgeois and industrial elites, who coveted urban townhouse mansions located close to the services, clubs, and institutions they patronized as well as estates in the counties outside the city. The development of mansions on and around Rittenhouse Square began about 1840 and expanded westward for the rest of the century. Prominent among these was the Fell-Van Rensselaer House (built 1896–98), a Beaux-Arts masterpiece located at Eighteenth and Walnut Streets. Mansions were sometimes the work of a quirky collector or designer, as in the case of one of the region’s more unusual mansions, Fonthill, a concrete castle built between 1908 and 1912 by Henry Chapman Mercer (1856–1930) in Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

For those somewhat lower on the social ladder, large houses sprang up in commuter communities such as Germantown and, later, Chestnut Hill, in the northwest part of Philadelphia. Although often referred to as mansions, these dwellings housed the prosperous middle classes. The Ebenezer Maxwell (1827–70) Mansion in Germantown (1859) typified what, in 1856, Philadelphia historian John Fanning Watson (1779–1860) called “fancy cottages for city business men.”

Following the development of the Pennsylvania Railroad in the nineteenth century, Philadelphia’s Main Line became a center of estate development and mansion building unparalleled in the region. One of its most prominent mansions, Ardrossan (1909–11) by Horace Trumbauer (1868–1938), a forty-five-room Georgian-style mansion, famously inspired the 1940 film The Philadelphia Story and shaped the perception of Philadelphia’s mansions and the people who inhabited them within popular culture. Another suburban mansion that drew particular attention was the one-hundred-thousand-square-foot Whitemarsh Hall in Montgomery County (1916–21, demolished 1980), one of the largest houses constructed in America. Additional regional nodes of mansion development included houses like those for the DuPont family in Delaware, such as Winterthur (1837–39, additions 1902, and 1928–32) and Nemours (1909–10).

Preservation Efforts

Active building of the largest mansions slowed dramatically after the Second World War. Many older mansions remained privately owned, while others became the focus of preservation efforts as the region’s historic infrastructure came under threat. Philadelphia-area elites continued to commission occasional architect-designed large private residences. The $80 million, thirty-seven-thousand-square-foot Alter Mansion (Arbor Hill Estate) designed by Rafael Viñoly (b. 1944) in Whitemarsh Township (1990s), which necessitated destruction of an earlier 1929 Normanesque Revival house, stands as a modern testament to the possibilities and pitfalls of mixing finance and architecture. A more pervasive form of late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century development was the “McMansion,” the large, suburban houses frequently built by real estate developers to provide housing to the region’s affluent professional and commercial classes that often have been considered lacking in architectural style and oversized.

Mansions remained visible physical symbols of the Philadelphia region’s past into the twenty-first century. They served as monumental examples of a version of history focused on wealth, social status, and hierarchy and symbolize the ebb and flow of development in a large American city and its region.

Stephen G. Hague teaches British and modern European history at Rowan University. His research interests center on social, cultural, and architectural history, and he is the author of The Gentleman’s House in the British Atlantic World, 1680–1780. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Mt. Airy: Yesterday and Today: Phil-Ellena - Greek Revival Palace (WHYY, April 9, 2012)

- Stenton mansion to undergo $800K landscaping 'rejuvenation' (WHYY, September 9, 2013)

- Maxwell Mansion savors Historical Society of Pa. award (WHYY, July 15, 2013)

- Colonists may have lost, but Philadelphians win at the Battle of Germantown (WHYY, October 4, 2013)

Links

- Cliveden: An Historic Germantown Mansion Redefines its Mission (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Traitor's Nest: Mount Pleasant (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Stenton Park: Green, Historic and Minutes Away (PhillyHistory Blog)

- “The Cliffs”: Fairmount Park Ruins with a Link to Joseph Wharton (PhillyHistory Blog)

- The Woodlands Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Cryptoporticus Exposed: Tunnels Beneath Woodlands Mansion Bare All (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- In Fairmount Park, “Unsurpassed” Collection Of Mansions Dressed For The Holidays (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- House Museum in North Philly Plans Monument for Former Slave (Hidden City Philadelphia)