Manufacturing Suburbs

Essay

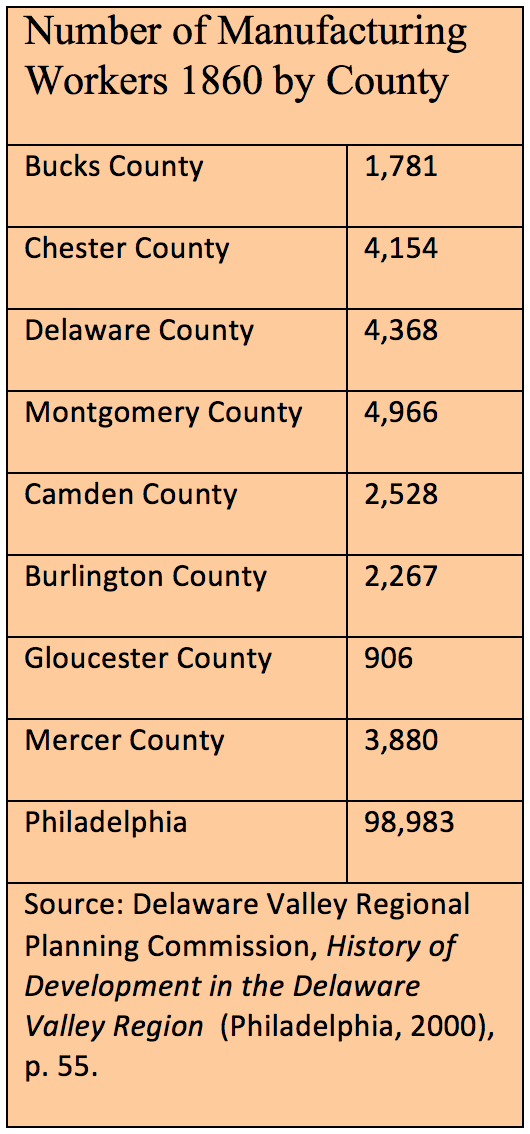

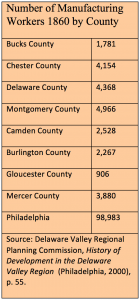

Although early industrialization in the eighteenth century took root mainly in urban centers, a substantial share of the Philadelphia region’s early manufacturing sprang up in small towns outside the young city. The explanation for that pattern lay in the region’s great rivers, the Delaware and Schuylkill. As early as the eighteenth century, enterprising settlers saw that the fast-moving currents in those rivers could drive water wheels to power grist mills, sawmills, paper mills, and iron foundries, and they built such businesses along the banks. When coal-fired steam engines overtook both water wheels and hand work, some of those early producers remained on the rivers’ edge since waterways provided affordable transportation for raw materials and finished goods. Thus, the map of early suburban manufacturing followed the region’s main waterways, a pattern that eventually influenced the paths of subsequent transportation networks of rail lines and highways.

In the first half of the nineteenth century canals enhanced the region’s rivers by extending their reach into the hinterlands and overcoming obstructions along particular stretches of river. Canals served especially to transport anthracite coal from the northeastern Pennsylvania coal fields to riverfront manufacturing towns. For example, Bristol Borough in Bucks County began to prosper as a manufacturing center on the Delaware River twenty-three miles northeast of the city after the Lehigh Canal built in 1829 connected Bristol with the state’s anthracite coal fields located near Mauch Chunk (later renamed Jim Thorpe) in Carbon County. Bristol’s industrial base expanded substantially in 1876 when William Grundy (1836-93) moved his woolen mill from Philadelphia, producing rugs, carpets, hosiery, and cloth. In 1815 the Schuylkill Navigation Company began construction of a canal connecting Philadelphia to Pottstown, making possible the emergence of Manayunk as a mill town on the banks of the river. By 1830 the canal had reached northward into the state’s coal region via Port Carbon, Pennsylvania, prompting its textile mills to mechanize to such an extent that Manayunk acquired the unflattering label “the Manchester of America.”

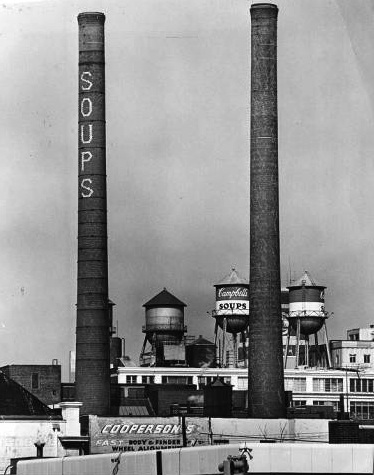

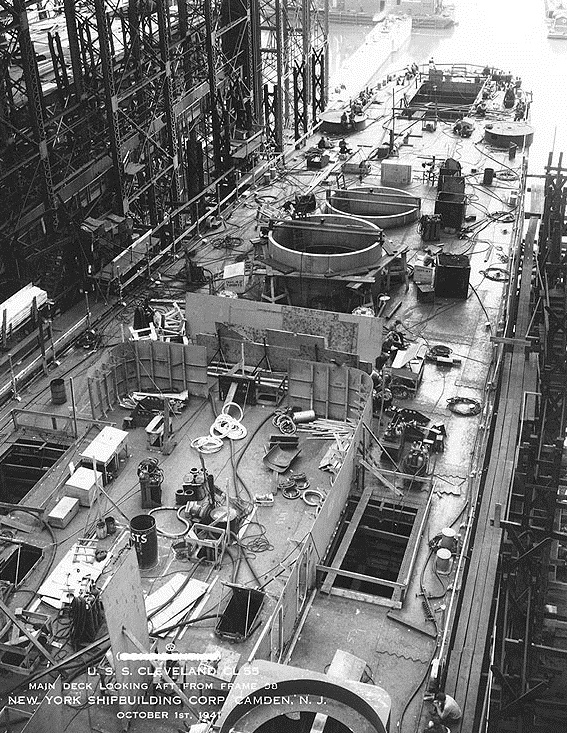

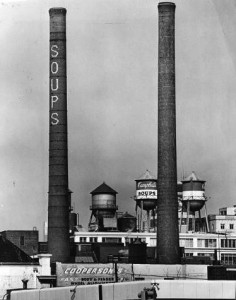

A few of the manufacturing clusters outside Philadelphia grew to become small cities. The city of Camden, New Jersey, across the Delaware River from Philadelphia developed a diversified manufacturing base in the nineteenth century by producing woolens, carriages, writing pens, and, most famously, Campbell’s Soup. The New York Shipbuilding Corporation began operations in 1899 on 160 acres in Camden, where the company built ships in assembly-line fashion, from barges to passenger liners and battleships. By World War II, it had become a central engine of Camden’s economy. Down the Delaware River from Philadelphia, the city of Chester in Delaware County based its prosperity on a diverse manufacturing base that included shipbuilding, textiles, metal products, and paper. Unlike smaller manufacturing suburbs, cities like Camden, Chester, and Wilmington developed beyond their manufacturing base. They gained prominence as hubs of transportation (mainly ports and railroads) and regional business services like banking, finance, and insurance.

A few of the manufacturing clusters outside Philadelphia grew to become small cities. The city of Camden, New Jersey, across the Delaware River from Philadelphia developed a diversified manufacturing base in the nineteenth century by producing woolens, carriages, writing pens, and, most famously, Campbell’s Soup. The New York Shipbuilding Corporation began operations in 1899 on 160 acres in Camden, where the company built ships in assembly-line fashion, from barges to passenger liners and battleships. By World War II, it had become a central engine of Camden’s economy. Down the Delaware River from Philadelphia, the city of Chester in Delaware County based its prosperity on a diverse manufacturing base that included shipbuilding, textiles, metal products, and paper. Unlike smaller manufacturing suburbs, cities like Camden, Chester, and Wilmington developed beyond their manufacturing base. They gained prominence as hubs of transportation (mainly ports and railroads) and regional business services like banking, finance, and insurance.

Manufacturing Villages

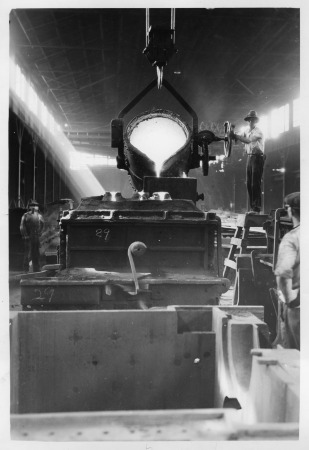

By contrast, other early manufacturing villages remained small, focused on one or two industries. On the west side of Philadelphia, ten miles up the Schuylkill River, the town of Conshohocken spawned iron works on a canal alongside an unnavigable stretch of river. The first foundry was built in 1844. The longest-surviving firm was Alan Wood & Co., which established the Schuylkill Iron Works plant there in 1857. By 1920 Alan Wood Steel could produce 500,000 tons of steel a year. It remained the economic mainstay of Conshohocken until the mid-twentieth century. Many such towns specialized: Phoenixville produced steel; Gloucester City housed DuPont Chemicals; and asbestos plants fueled Ambler’s growth. Although they remained small, these nineteenth-century manufacturing towns shared some features in common with cities, including a land use pattern that mixed together manufacturing, housing, and walkable commercial districts where craftsmen, tradesmen, and merchants clustered. That surviving land-use pattern differentiated early manufacturing communities from twentieth century suburban towns.

Not every important industry located on a river bank. Some chose locations near an important source of raw materials. For example, glass manufacturing flourished during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries on the New Jersey side of the Delaware River, particularly around the town of Glassboro in Gloucester County, named for the distinguished craftsmanship of what came to be known as “South Jersey Glass.” The quality of southern New Jersey’s sand, a major ingredient in glass manufacture, helped to establish its reputation, while its proximity to Philadelphia provided a large market for the industry.

In the first three decades of the twentieth century, more manufacturers built factories in the suburbs, attracted by cheap land and enabled by cheap energy. In 1916 Sun Oil chose to locate Sun Shipbuilding Co. in Chester in Delaware County eighteen miles downriver from Philadelphia. That plant grew quickly by delivering tanker ships to serve in World War I. In 1906, Baldwin Locomotive expanded its massive Philadelphia operations by building a suburban plant in Eddystone in Delaware County, about twelve miles south of Philadelphia on the Delaware River. In 1925 the Ford Motor Co. transferred its regional operations from North Philadelphia to Chester, where it found more space and more efficient transportation for finished cars. Another major auto manufacturer, General Motors, opened a components factory upriver from Philadelphia in 1938 in West Trenton.

The Depression dealt a dramatic blow to many of these plants. Markets for their products collapsed in the 1930s, but business revived during World War II. Military contractors in Camden, Chester, and many parts of Delaware, Montgomery, and Bucks Counties employed thousands of defense workers. Sun Shipbuilding once again constructed vital oil tankers for a Navy that fought a war on two oceans, while New York Ship built aircraft carriers and battleships.

Lure of the Highway

Once the expanded highway network of the 1960s and 1970s increased access to undeveloped parcels of land outside the city, manufacturing spread more widely across the region. Rather than concentrating in towns, many manufacturers chose to build near highway off-ramps to speed transportation in and out of their plants, creating a highly dispersed pattern of industrial development.

To counteract the flight of industrial jobs, the city created its own industrial park in Northeast Philadelphia. In that sparsely populated section of the city, the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation assembled large parcels of land during the 1960s and equipped them with water, sewer, and other industrial infrastructure. In effect, the city developed its own manufacturing “suburb” within the city limits.

In the space of only a few decades, however, new forces emerged to further challenge both city and suburbs. Obsolete technologies, coupled with competition from low-wage producers around the globe, forced many suburban manufacturers out of business. When diesel technology eclipsed Baldwin’s steam engines, the company suspended operations in 1956 and, after several mergers, closed in 1972. Alan Wood Steel Co. closed its Conshohocken plant in 1977, driven out of business by foreign steel. U.S. Steel managed to keep its Fairless Hills Plant in Falls Township, Bucks County, open, but only until 1991.

Manufacturing Persists

Despite a broad regional decline in manufacturing, the Philadelphia metropolitan area remained competitive in various forms of advanced manufacturing that make use of new materials and processes enabled by nanotechnology or other scientific innovations. Those include pharmaceuticals, medical devices and equipment, precision instruments, plastics, chemicals, aircraft, and other defense industries.

As factory after factory fell victim to overseas competition and outsourcing, the loss of that industrial base brought a host of fiscal and social problems to manufacturing suburbs, including distressed schools, brownfields, deteriorating housing stocks, and stagnating tax bases. Populations aged in some of these suburban towns because the housing stock turned over so slowly that homeowners could not find buyers for their houses. Even in towns that were able to attract new populations, including African American and immigrant families, often the newcomers’ incomes and property values could not provide an adequate tax base for services.

Yet manufacturing suburbs also offered significant opportunities for redevelopment. Towns built before the automobile resembled the city’s industrial neighborhoods, densely developed with worker housing built within walking distance of manufacturing plants. They remained walkable communities usually with a main street commercial district. Planners and developers recognized a preference among some homebuyers for higher density housing in communities with historic character that allowed residents to rely less on automobiles and more on walking, bicycling and passenger rail lines serving many older river towns. The market potential was especially high for manufacturing suburbs built along rivers because of the premium that real estate markets place on waterfront locations. In places like Conshohocken and Bristol, developers repurposed mills, lofts, and other industrial buildings to house offices and commercial businesses. The success of such projects led regional planners to recognize that old manufacturing towns could help concentrate future commercial and residential development and lessen sprawl.

Carolyn T. Adams is Professor Emeritus of Geography and Urban Studies at Temple University and associate editor of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Why did the 'Workshop to the World' bustle, then wither? (WHYY, October 15, 2011)

- Fire rips through Camden manufacturing plant (WHYY, June 19, 2012)

- Gun manufacturer leaving New York for Pennsylvania's Pike County (WHYY, August 8, 2013)

- New survey shows confidence building among Philly-area manufacturers (WHYY, November 28, 2014)

- What should the future be for Claymont? (WHYY, June 6, 2016)

- National Museum of Industrial History opens in Bethlehem (WHYY, August 2, 2016)