Mercer Museum

Essay

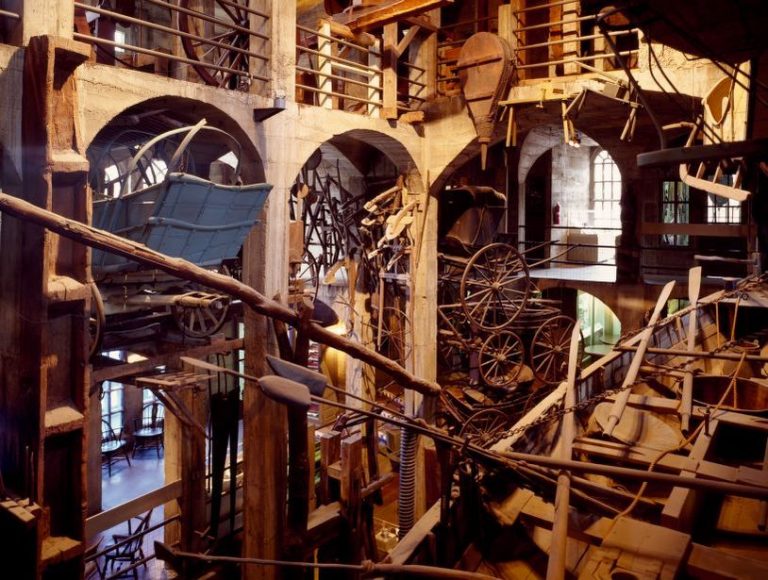

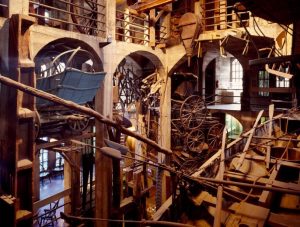

Henry Chapman Mercer (1856-1930) began collecting the tools of preindustrial America in 1897, just as they were becoming irretrievable even from the junk pile. He called his collection “Tools of the Nation Maker” to reflect their purpose and function in everyday life and the construction of the nation. The collection became the centerpiece for the Mercer Museum, which opened in 1916 in a dramatic concrete castle designed by Mercer himself in Doylestown, Pennsylvania. In many ways, the museum changed little over the next century with Mercer’s displays and his system of organization intact. However, over time the museum variously interpreted the collection as a dialogue between tradition and progress, a connection between the artisans of the past and the crafters of the present, and a catalyst for a community sense of history.

Born in 1856 in Doylestown, Mercer came from a wealthy family and spent most of his life in Bucks County. As a young man, his exposure to the Arts and Crafts Movement through Charles Eliot Norton (1827-1908) during Mercer’s time at Harvard encouraged an interest in craftsmanship and the preindustrial past. His participation in the founding of the Bucks County Historical Society in 1880 was also a sign of his lifelong interest in local history. Yet an 1876 visit to the Centennial Exhibition’s spectacle of technology and progress equally fostered an emerging interest in the links between the American past, its present, and its future. In addition, his stint as a curator of archaeology at the University Museum at the University of Pennsylvania from 1894 to 1897 was equally pivotal in forming his attitude toward the importance of collecting objects as historical evidence.

Despite the importance of these varied experiences, in relating the origins of his collection Mercer told a different story. At a meeting of the Bucks County Historical Society in 1907, Mercer explained that one day in February or March of 1897, he went to the country seeking a pair of tongs for an old fireplace, hoping to find them in “penny lots … that is to say valueless masses of obsolete utensils or objects which were regarded as useless.” However, “when I came to hunt out the tongs from the midst of a disordered pile of old wagons, gum-tree salt-boxes, flax-brakes, straw beehives, tin dinner-horns, rope-machines and spinning-wheels, things that I had heard of but never collectively saw before, the idea occurred to me that the history of Pennsylvania was here profusely illustrated and from a new point of view.” So was born the “Tools of the Nation Maker” collection that soon became Mercer’s museum dedicated to the preindustrial history of the United States as seen through its artifacts. Mercer collected the preindustrial tools of the colonial era that gave birth to the United States, but in doing so he also collected the history of settler colonialism and the European immigrants who used those tools to displace indigenous people and to conquer the North American environment and its natural resources.

The Original Exhibit, 1897

Mercer and the Bucks County Historical Society installed “Tools of the Nation Maker” in 1897 as an exhibit in the Bucks County Courthouse. As historical artifacts, the tools documented the creation of the nation and the life of a community. As archaeological artifacts, they provided, in Mercer’s words, “a history of our country from the point of view of the work of human hands.” They also represented a moment in time that was rapidly being lost. Mercer focused on saving tools from the era before 1820 and the advent of steam power and industrialization. By saving the artifacts, he hoped to also preserve the work of the past in the face of new modes of industrial production that were rendering obsolete not only the tools but also artisans and their craftsmanship. There seemed to be little nostalgia in Mercer’s work. Mercer collected not to mourn the loss of an idyllic past, but to demonstrate its relevance to human identities, communities, and the nation.

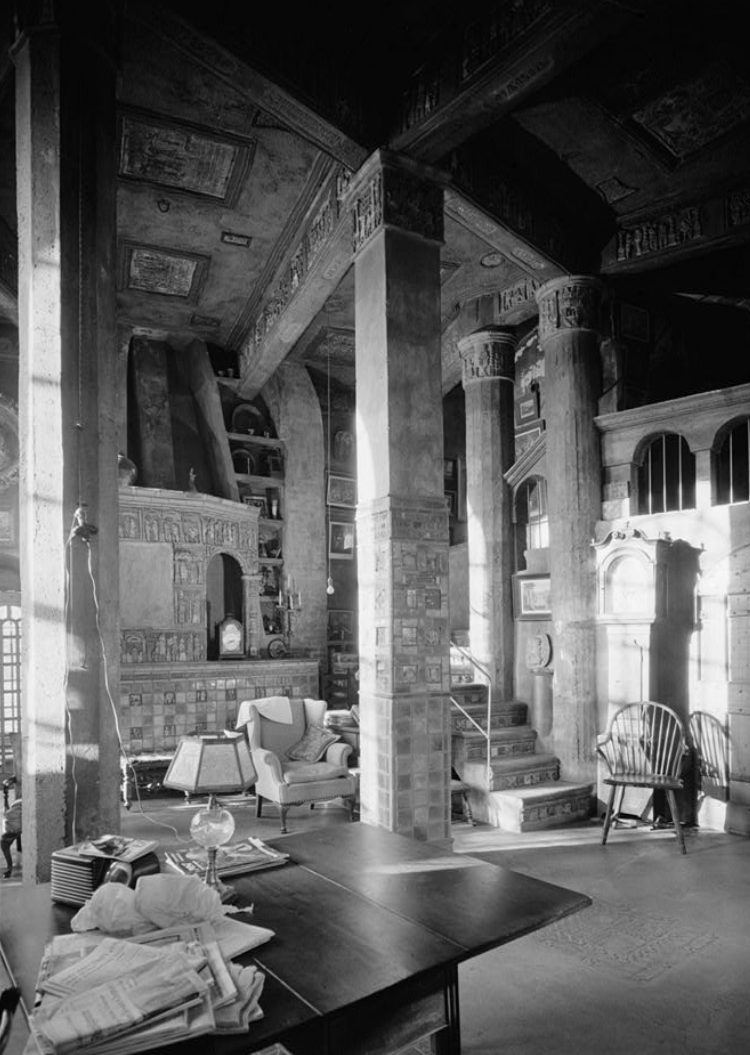

In 1905, Mercer’s aunt left him a large sum of money, which he used to build his home at Fonthill Castle in 1910, the Moravian Tile Works in 1912, and finally the Mercer Museum in 1916. Mercer built all three buildings out of reinforced concrete without blueprints or any other plan besides sketches in his own notebooks. If an error was made in constructing some part of a building, it was torn down completely and rebuilt.

The Mercer Museum’s six-story building “was made for the collection, while the collection was not made for it,” Mercer said. From a central court at the heart of the museum, three floors of galleries spiraled. At each level, rooms and niches of various sizes each displayed dozens of examples of a single type of tool that served a specific function and helped fulfill a specific human need. These moved steadily upwards from tools used to fulfill primary needs on the lower floors—food, clothing, shelter, transport—to secondary needs on the upper floors—religion, art, science, amusement. The objects simultaneously explained human civilization and provided a connection to history by inviting visitors to look at them as tools that made even the smallest, most overlooked aspects of everyday life possible.

In 1923 and again in 1925, Henry Ford (1863-1947) came to Doylestown as research for the museum he was building outside of Detroit. Ford and Mercer shared a concern for salvaging the history of preindustrial America through the everyday artifacts of everyday people. In this, both represented a departure from the professional, university-based field of history that emphasized the military and political campaigns of men like George Washington (1732-99) through documents and writing. Yet Mercer still presented a heroic historical narrative of colonialism, focused instead on celebrating the pioneer spirit of the first European immigrants and those colonists who later set out in Conestoga wagons to conquer the West.

Another Wave of Progress

Upon his death in 1930, Henry Mercer donated the museum and an endowment to the Bucks County Historical Society. Responsibility for its operations passed to the curator, Horace Mann (1890-1951). Mann, like those after him, maintained the museum as a history of everyday people seen through their tools. By the 1950s, new anxieties and aspirations around modern tools and technology echoed Mercer’s earlier ideas, but for a new era. Like the end of the nineteenth century, the 1950s saw new and supposedly improved technologies displace older tools, modes of work, and forms of everyday life in the name of progress. As at the turn of the twentieth century, this also brought with it a turn to the American past and to constructions of the nation, its heritage, and its traditions where white pioneers and their descendants were heroes and non-white people were all but absent. In this context, the Mercer Museum resonated in a society that continued to look forward and back, seeking stories of progress, tradition, and nostalgia that justified current social relationships in order to help manage modern life in the face of social change.

The post-World War II era influenced the museum in other ways as well. The growth of Philadelphia suburbs, highways, and car culture made the Mercer Museum a tourist attraction as well as a scholarly resource and a display of local history. Over the course of the 1960s and 1970s, the museum instituted an admission fee and added membership programs, public lectures, and services for school groups. Collections management grew as well, with cataloging the vast collection a perpetual concern. The museum also worked to preserve artifacts, reinstall exhibits, and add labels to make the history Mercer wished to represent legible to nonexpert audiences in a new era.

At the same time, a renewed dedication to demonstrating the functions of these tools also emerged. The first Folkfest, held in 1974, continued into the 2000s as an annual weekend event bringing in craftspeople and reenactors to show off historic practices that ranged from stonecutting and woodworking to folk dancing, calligraphy, and quilting. Workshops and multiweek courses taught some of these practices throughout the year. The emphasis on craft and the appeal to heritage and nostalgia repositioned the meaning of Mercer’s tools, but Folkfest and other events clearly extended Mercer’s understanding that these were not just artifacts, but tools whose uses expressed their purposes.

Museum Expansion

The museum completed an expansion in 2011 that included classroom space for school groups and exhibit space for temporary displays. Exhibits included displays of the museum’s larger collection as well as exhibits of fine art, contemporary craft, and history, including a new generation of twentieth-century social and cultural history. Although the museum still hosted events with demonstrations and nostalgic, colonial-era activities, in the twenty-first century, more diverse exhibits began to drive programming, many of which incorporated new perspectives—some historical, some artistic, some scientific—on the old collections.

By 2019, the collection contained over forty thousand objects, about doubling what Mercer acquired in his lifetime. Of the sixty rooms that housed exhibits in the 1920s, twenty-four remained as they were, and a total of fifty-five rooms were filled. However, even when objects were reinstalled or rearranged, the organizational logic throughout the core of the museum did not change. The museum continued to collect to fill in gaps in Mercer’s collection, but also expanded its local collections to capture the wider scope of the twentieth century and more recent history. By the twenty-first century, the mission and vision focused less on the specific history of preindustrial tools and work that Mercer wanted to preserve, and emphasized community engagement, a renewed dedication to making the past relevant, and a strong sense of place. The main galleries remained faithful to Mercer’s intentions and his organizational system, but special exhibits and other programming reflected contemporary interpretation of tangible historical trends rather than the abstract history of obsolescence and the changing nature of work.

Mabel Rosenheck is a writer, lecturer, and historian in Philadelphia. She received her Ph.D. in media and cultural studies from Northwestern University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2020, Rutgers University