Mount Airy (West)

Essay

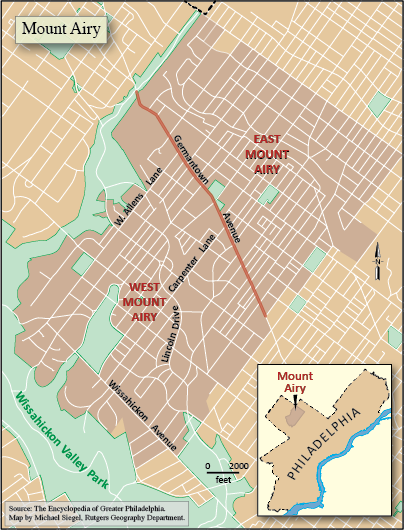

For more than sixty years, West Mount Airy, nestled in the northwest corner of Philadelphia, has earned a reputation as a national model of racial integration. In the years following World War II, when many American neighborhoods were experiencing rapid racial transition, homeowners in West Mount Airy worked to understand and put into practice the ideals of an integrated society. Through innovative real estate efforts, creative marketing techniques, religious activism, and institutional partnerships, residents worked to disrupt a system of separation and infuse their day-to-day lives with the experience of interracial living.

In 1950, West Mount Airy was home to 18,462 residents. Outside of the neighborhood’s Sharpnack section (an industrial village that had sprung up in the eighteenth century as a home for domestic workers and was, by the 1890s, known for its densely populated blocks of narrow two-story stucco homes), 98.6 percent of the community’s residents were white. As in urban neighborhoods throughout the northern United States, West Mount Airy residents experienced deep racial anxieties and worked hard to preserve what they saw as the integrity of their community. When Black migration from the South produced a sudden influx of African American buyers, they worried that their property values would diminish, that the instability would breed volatility and crime, and that their neighborhood institutions would fall apart. Enterprising realtors quickly stepped in, spreading rumors of mass home sales and projecting intense instability and a pronounced decline in housing values.

But many residents saw the possibility of something different. Not wanting to give in to the belief that racial transition necessarily brought about neighborhood decline, white homeowners sought to find a new strategy to preserve the viability of their neighborhood: by welcoming prospective Black buyers.

Diverse and Flight-Resistant

Mount Airy’s cultural, economic, and physical character created the possibility for purposeful and peaceful integration in the neighborhood. The community was home to a critical mass of high-achieving white residents. They were well educated, politically oriented, and liberally minded. Many worked with African Americans in their professional networks and were perhaps more open to friendly relations in their residential community as well. The neighborhood’s rich diversity in housing stock and proximity to Fairmount Park and the Wissahickon Gorge, difficult to replicate in other parts of the city or in the surrounding suburbs, also attracted a variety of people and made them more resistant to flight.

In 1953, a group of West Mount Airy homeowners, led by clergy from four area religious institutions, decided to learn all they could about local and national trends in housing and race relations. After months of research, they concluded from the evidence that a racially mixed neighborhood was both sustainable and, just maybe, even desirable. To preserve the material and cultural benefits of the neighborhood and to retain its economic viability, they decided to work to create interracial living.

At first, community leaders adopted a strategy of individual education and persuasion, including calling on residents to participate in “sell your neighborhood” campaigns and encouraging prospective buyers of “high standard” to purchase homes in the area. Through public sermons, focus groups, informal gatherings, and the creation of new community gathering spaces, these leaders promoted a positive attitude about the racial change that was occurring in the neighborhood.

High Cost of Living Promoted Stability

This approach was rooted in a sense of economic exclusivity. The high cost of living in the neighborhood meant that only the most financially stable buyers were able to purchase homes. Like the existing white community, upwardly mobile Black families who sought entry were invested in maintaining the economic and social status of the community. Organizers facilitated this de facto class-based exclusion by minimizing discussion of racial difference and by promoting the economic and cultural similarities among residents, Black and white, old and new.

The neighborhood began to see concrete results from community efforts within the first few years of transition, but this stability was precarious. As early as 1953, housing prices began to decline, and community leaders believed that real estate agents were directing most prospective Black buyers to the southeastern pocket of the neighborhood, where Black families first began to congregate at the beginning of the decade. Though these early efforts slowed the rate of change, by the late 1950s, some believed that creating long-term stability in an integrated neighborhood would require consolidating community initiatives.

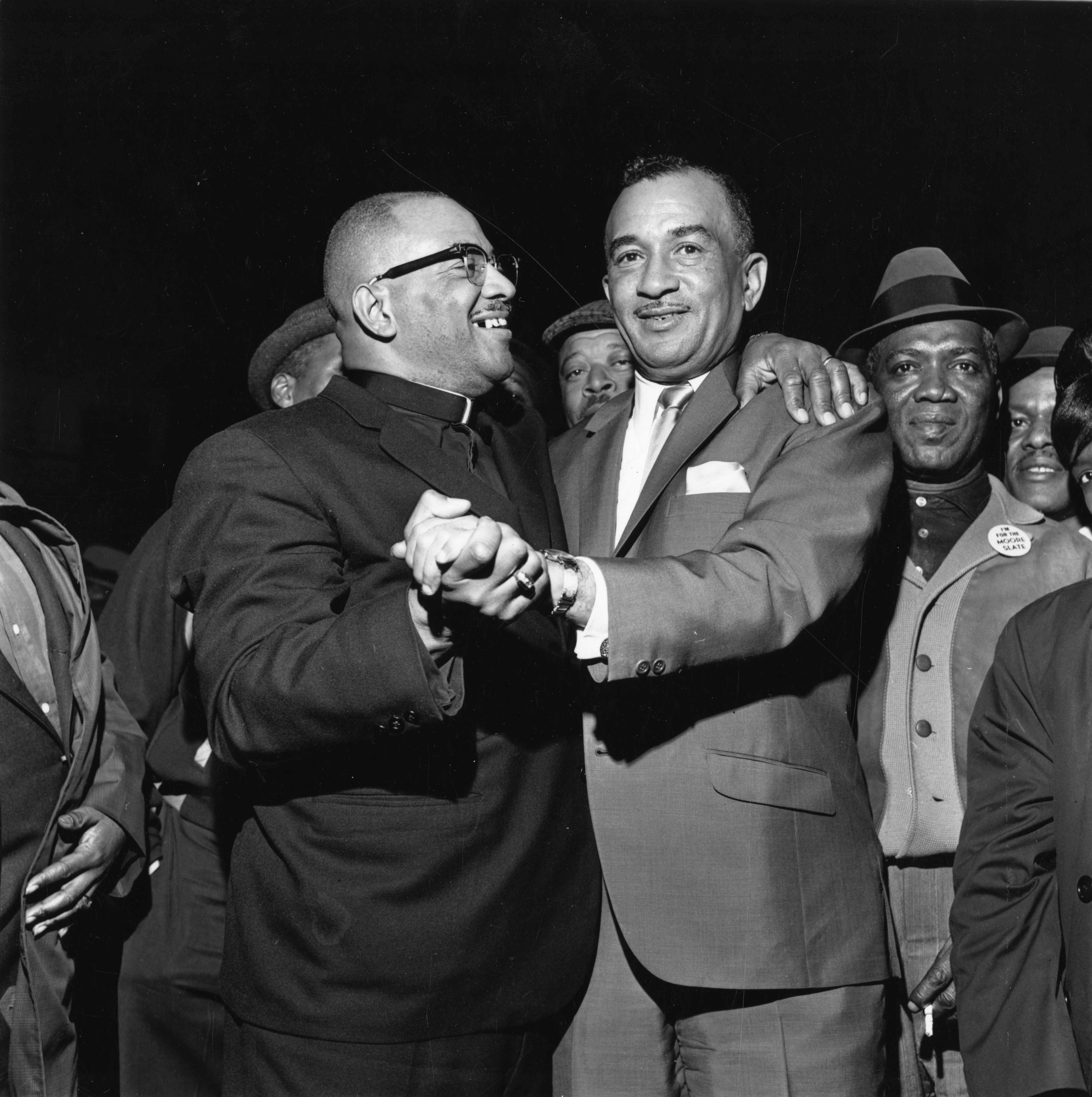

George Schermer (1910-89), a West Mount Airy homeowner and director of the city’s Human Relations Commission, believed that the community needed an infrastructure to connect individual responsibility with broader institutional authority. In 1959, under Schermer’s leadership, West Mount Airy Neighbors (WMAN) was born as a community clearinghouse for neighborhood organizing, an institutional collaboration that became the defining principle of West Mount Airy’s organizing success through the twentieth century.

But even as residential integration in the community stabilized, Mount Airy residents contended with shifting economic and political pressures and evolving notions of racial justice around the city and across the nation.

Debate in the Black Community

In the mid-1960s, local NAACP president Cecil B. Moore (1915-79) condemned both the class-based identity and the integrationist ideology of Mount Airy’s Black homebuyers as dangerous to the larger African American community. Moore’s attacks touched off intense debates over the very meaning of Blackness in urban space. As he tried to galvanize the Black masses of North Philadelphia, the NAACP leader saw West Mount Airy as an ideological dividing line in the city’s struggle for civil rights. African Americans moving to the Northwest Philadelphia neighborhood became symbols of Black middle-class complicity with the white establishment that Moore condemned. To Moore, the Black middle-class residents of Mount Airy represented African Americans who had abandoned the Black masses and thus given up their claims to Blackness. Such rhetorical battles between the NAACP president and the city’s liberal middle-class community highlighted rising tensions within the fight for racial justice.

Under pressure from larger cultural forces and public policies that tended to perpetuate segregation, community members struggled to redefine their mission and to maintain control over local institutions. External pressures became particularly heated around the issue of neighborhood schools. When West Mount Airy experienced its first hints of transition in the early 1950s, the neighborhood’s elementary schools were overwhelming white. As Black families began to move in, school demographics shifted rapidly, significantly faster than the neighborhood itself. Henry School, in the center of West Mount Airy’s integrated core, experienced this change particularly acutely.

In 1953, Henry had 400 white and 95 Black students. By the end of the decade, as Black families moved in and as the school district redrew catchment areas to contend with changing residential patterns in Northwest Philadelphia, enrollment of white students plummeted to 35 percent. By the middle of the 1960s, 275 white students and 560 African Americans attended Henry.

As parents wrestled with how best to negotiate the public schools, they were forced to consider their own responsibility to the surrounding communities. In 1959, West Mount Airy Neighbors board members contemplated a proposal to return to pre-1953 catchment boundaries, a change that would have sent a substantial number of lower-income Black students from Henry School to the nearby, but overcrowded, Emlen School. Some believed that it was in the best interest of West Mount Airy to remake the elementary school in the image of the neighborhood. Others argued that local integration should only be a goal insofar as it did not create discriminatory conditions elsewhere.

Ultimately, the committee abandoned the proposal, but such questions of equity and justice persisted through the end of the twentieth century.

Stability and Diversity Endure

By the second decade of the twenty-first century, West Mount Airy remained one of the most economically stable and diverse areas in Philadelphia. At the time of the 2010 census, the neighborhood was roughly 41 percent African American, 54 percent white, and 5 percent Asian or Latino, with 3 percent of residents self-identifying as multiracial. Between 2005 and 2009, the median household income in West Mount Airy was nearly $85,000, almost 60 percent higher than the national median for the same period, with more than a third of residents having earned graduate degrees. In March 2013, the Pew Charitable Trust named the 19119 zip code, which encompasses both East and West Mount Airy, the seventh-wealthiest zip code in Philadelphia. The community also continued to be a haven for alternative families and progressive politics, evidenced by hybrid cars with bumper stickers proclaiming “Support Organic Farmers” and “Keep Abortion Legal.” At the corner of Carpenter Lane and Green Street, the center of the original integrated core, the Weaver’s Way Co-op, the Blue Marble Bookstore, and the High Point café, provided every indication of a thriving, open community.

A more nuanced evaluation of the neighborhood, though, reveals racial isolation increasing and a class-based exclusivity continuing to pervade local housing patterns. Between 1990 and 2010, the population of West Mount Airy decreased from roughly 17,500 to less than 10,000, with Black residents accounting for 70 percent of that loss. In that same period, block-by-block integration saw a sharp decline. In 1990, the typical Black resident lived on a block comprised approximately 75 percent of African Americans; by 2010, the same blocks had become almost entirely Black. Furthermore, in 1990 African Americans were dispersed relatively evenly throughout the neighborhood, but by 2000 they were disproportionately clustered in the southern and eastern regions of the community, adjacent to poorer and Blacker East Mount Airy and East Germantown. These numbers indicated a continuing and growing economic divide. In the early twenty-first century, the economic status of residents remained a key factor for achieving residential integration and cultural diversity.

This demographic profile of West Mount Airy at the turn of the twenty-first century was set against a growing national critique of the very idea of integration. Echoing Cecil Moore’s condemnations in the 1960s, by the late 1990s, some had come to view post-war integration as an effort by white liberals to heal the nation’s fractured race relations without reshaping its power structure. As these commentators write, in the decades following World War II, integration had become the mainstream rallying cry of the civil rights movement. But even as activists made strides in eroding legal barriers in employment, education, and housing, these triumphs revealed the limits of integration, in its failure to bring about fundamental changes in the material conditions of American society.

These larger critiques reflect the history of West Mount Airy itself. The area’s integration efforts allowed long-standing residents to maintain the integrity of their neighborhood by welcoming similarly situated African Americans. Together, they created a community grounded in the ideals of postwar racial liberalism, and they fought hard to maintain that ideal amid shifting economic and political pressures and evolving notions of racial justice. But the Mount Airy integration project never sought to be transformative; at its core, the neighborhood efforts were grounded in a desire to preserve their community and to retain its viability through celebrating interracial living.

Abigail Perkiss is an Assistant Professor of History at Kean University in Union, N.J. She is the author of Making Good Neighbors: Civil Rights, Liberalism, and Integration in Post-War Philadelphia, published by Cornell University Press. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History