Mütter Museum

Essay

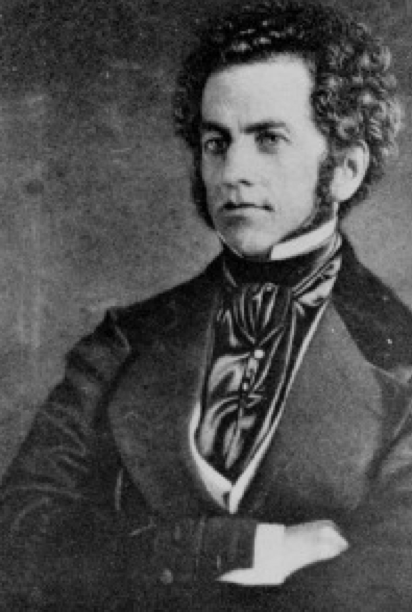

In 1849, the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, following trends in medical education and research, created a museum of anatomy and pathology. After Thomas Dent Mütter (1811-59) donated his world-class collection in 1858, the expanded institution became the Mütter Museum—one of the best medical collections in the city and in the country. Together, as their missions evolved, the museum and the college showed that a collection from the nineteenth century could be engaged in new ways for new visitors, both medical and non-medical. In the twenty-first century, the museum addressed contemporary concerns in the fields of medicine and public health while also documenting the history of science and evoking larger meditations on life, death, and the human body.

Mütter, who graduated from medical school at the University of Pennsylvania in 1831, taught and practiced medicine at Jefferson Medical College as the Chair of Surgery from 1841 until 1856. While doing so, he built the collection of more than a thousand items that he donated to the college along with a $30,000 endowment to maintain the collection and fund a lectureship. Bones, wet preparations, casts, and watercolor paintings dominated the gift, which also included wax preparations, dried preparations, papier-mache models, and oil paintings.

Mütter stipulated that the College of Physicians (founded in 1787) construct a new, fireproof building to house the collection within five years of his donation. In 1863, the requisite building opened at Thirteenth and Locust Streets, and over time the museum’s collections expanded through additional gifts, donations, and purchases. The collections were meant to be educational, but because the Mütter was never part of a medical school they served the continuing education of members of the college more than doctors in training. However, little is known as to how widely members used the museum. Ambivalence about the museum emerged despite the time, money, and other resources put into acquisitions. Upon the centennial of the college in 1887, some, like S. Weir Mitchell (1829-1914), praised the museum as “one of the most valuable and interesting collections in America.” Others, like W.S.W. Ruschenberger (1807-95), suggested that “many visit the museum merely to gratify curiosity. How many resort to it only for study, or consult it for information alone, has not been ascertained.”

Restrictions on Use of Museum Income

Some of the ambivalence resulted from the fact that surplus income from the Mütter endowment could not be used by the college for other purposes. The library in particular needed more space, and library staff as well as many members of the college viewed old pathological specimens as less useful than books and journals containing current information on medical research. While specimens could best teach lessons in older fields like anatomy, books were more useful in emergent laboratory-based fields like bacteriology. Ultimately, the college used income from the endowment to add a third floor that benefited the library as well as the growing museum. The expansion opened in 1886.

By the turn of the twentieth century, however, the college needed still more space and constructed a new building at Twenty-Second and Ludlow Streets. The building, completed in 1909, had dedicated space for the museum, although more room for the library stacks. The design of the exhibit space emulated museums in Europe with an open lower level surrounded by a mezzanine that let natural light into the gallery. Some of the wood and glass display cases likely came from the old location and newer cases resembled the nineteenth-century originals.

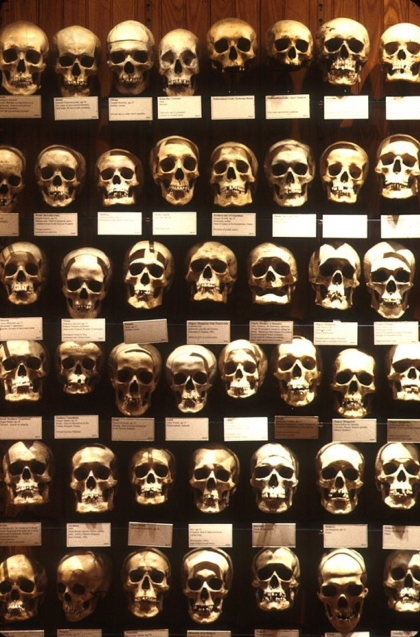

The architecture, cabinetry, and specimens remained the same into the twenty-first century—garnering the Mütter a reputation as a museum of a museum. Retained historical exhibits included the American Giant seen alongside Mary Ashberry, a dwarf, and the Hyrtl Skulls organized row upon row for easy comparison and aesthetic appeal. Other displays, such as congenital deformities, survived with the arrangements and labels of an earlier date, but curators added text to explain the labels as historical documents that included past language that had become derogatory and offensive.

Despite the new home established in 1909, the collections languished throughout much of the twentieth century because education and innovation in the medical field shifted to subjects like microbiology, which did not use the same specimens that anatomy and pathology once had. The Mütter’s utility was also limited because medical students still had access to collections at their home institutions and gaining entry to the museum required a discouraging amount of paperwork. However, as part of a medical society rather than a school, the Mütter remained insulated from needs to align with new methods of learning or jettison space-consuming specimens and thus it survived when its peers did not.

Visitation Diversifies

In the mid-twentieth century, curators like Ella Wade (1892-1980) and Elizabeth Moyer (1917-97) cared for the collections and administered visitation permissions to medical schools, nursing schools, and biology classes. By the 1970s, attendance diversified when students from Moore College of Art came to the museum to sketch and other casual, nonmedical visitors came in somewhat greater numbers. A boost came from the 1976 Bicentennial when the Philadelphia Visitor and Convention Guide listed the museum in its brochure, presenting it both as a tourist attraction and as a site of American heritage.

Also in the mid-1970s, Gretchen Worden (1947-2004) began her 29-year tenure at the institution, a career that transformed the Mütter Museum into a Philadelphia icon far better known to the public than the College of Physicians. Not all at the college welcomed this development. Despite those members, however, the museum attracted more and more visitors—growing from 1,800 in 1959 to 5,000 annually in the 1980s and to 24,000 in 1997. It also faced new problems of interpretation. While the medical field had been historically comfortable with the objectification of people with diseases and disabilities—labeling them monstrous and grotesque—nonmedical visitors, new codes of medical ethics, and progressive approaches to museum exhibition changed curatorial strategies.

Confronted by these new interests, the twentieth-century museum had to face its nineteenth-century roots as both a medical institution and as a museum. When the Mütter Museum was established, emerging ideas about medical authority, scientific objectivity, and technologies like photography—which the Mütter collected—had a tendency to overlook the human pain of disease and disability and diminish the individuality of the patient. The museum, with its objects and body parts, had a parallel effect. In addition to reflecting the earlier approach to medical practice, the Mütter Museum developed from a Victorian-era interest in objects as things that could be ordered, controlled, and mastered amidst an unruly and rapidly changing world.

By the late twentieth century, changing ethics in both medicine and museums meant that displays of body parts could seem exploitative, and nonmedical visitors could seem like voyeurs taking pleasure in the disembodied pain of others. Although the collections could still be informative for nonmedical visitors who might view the collections with respect, their spectatorship could also easily look like gawking at diseased bodies for entertainment.

Pathology With an Artistic Bent

Worden’s approach to this problem focused on the collections’ hidden aesthetics. Rather than seeing pathology as ugly, grotesque, or abnormal, she invited art photographers to take pictures of the specimens and to show the body—even the diseased body—as beautiful, as a testament not to horror, but to humanity. New projects, including the calendar she created with artist Laura Lindgren (b. 1959), photography exhibits in the museum, and fellowships for artists to use the museum and library reoriented the collections away from exclusively medical constructions of the body as object and toward conventions of fine art that conveyed respect and fostered reflection.

In the 2000s, curator Anna Dhody (b. 1974) helped the College of Physicians establish exhibits and programs to engage the historic collections with contemporary concerns about public health. A History of Vaccines website launched in 2010. Interpretive labeling evolved. In other programs, LGBTQ+ youth gave tours that used the Hyrtl collection to show the difficulty of identifying gender—much less race—based on bone structure. Additionally, the Mütter Research Institute created in 2014 encouraged modern research with the historic collections.

Begun with a world-class medical collection in the nineteenth century, in the twentieth century the Mütter Museum became a relic maintained through inertia and the support of the College of Physicians as a home institution. By the twenty-first century, however, the museum took advantage of its reliquary status and adopted new roles as a document of medical heritage, a meditation on disease, life, and death, and an exploration of the simultaneous beauty and monstrosity of the body and of humanity itself. As a tourist attraction that garnered over 180,000 visitors a year, the museum no longer simply survived within the auspices of the College of Physicians, but helped finance it. Indeed, plans for the expansion of exhibit space announced in 2018 demonstrated that the museum was driving not only the public identity and financial security of the College of Physicians but also broader conversations about public health and public history.

Mabel Rosenheck is a writer and historian in Philadelphia. She received her Ph.D. in media and cultural studies from Northwestern University and works at the Wagner Free Institute of Science, Temple University, and elsewhere. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Twelve short stories inspired by the Mutter Museum (WHYY, May 3, 2012)

- Mütter gives new life to Founding Father’s medicinal garden (WHYY, September 15, 2018)

- Philly woman with rare bone disease donates skeleton to Mütter Museum (WHYY, Februrary 29, 2019)

- Mütter Museum to double medical abnormalities exhibits (WHYY, June 5, 2019)

Links

- PhilaPlace: The College of Physicians (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: College of Physicians: Revolutionizing Medicine — Thomas Dent Mütter of the College of Physicians (Historical Society of Pennsylvania))

- The College of Physicians of Philadelphia

- Growing Pains Yield Gains For The Mütter Museum (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- The Mütter Museum of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia