Petty Island

Essay

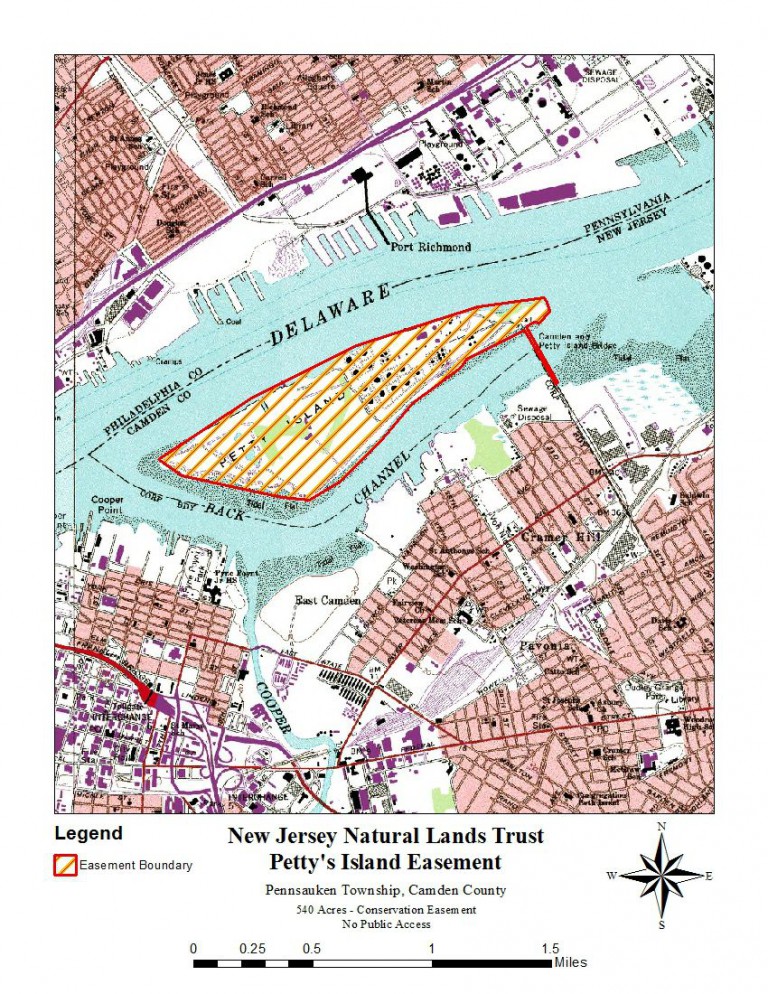

Petty Island, part of Pennsauken, New Jersey, in the Delaware River opposite the Kensington section of Philadelphia, played a significant supporting role in the economic development of the region. Also known as “Pettys” or “Petty’s” Island, over time it served as a place where people hunted, fished, gathered herbs, farmed, built and repaired boats, operated blacksmith shops and sawmills, manufactured wagons and chains, ran a drinking and dancing establishment, conducted lotteries, stored coal and petroleum products, refueled ocean-going vessels, refined oil, and operated a port. In 2009 the island began a transition from industrial use to a future as a state-owned wildlife preserve.

Thomas and Elizabeth Fairman’s home, inaccurately depicted in the background of this 1771 Benjamin West painting, also housed the first deputy governor of Pennsylvania and William Penn during his 1683 conference with Lenape Leaders. (Pennsylvania Academy for the Fine Arts)

According to a 1655 map by Peter Lindstrom (d. 1691), the region’s original inhabitants, the Lenni Lenape, called the island Aequikenaska (“where the panther ran”). When Elizabeth Kinsey (c. 1650-1720) purchased the island in 1678, the deed recording the sale described it as the “great island lying before Shaksemasen,” a reference to a former Lenape meeting place and the location of her plantation home on the west side of the river. Kinsey’s deed contained provisions that exemplified early Quaker policy for good relations with the Lenape: it spelled out their right to continue to hunt and fish on the island, their promise not to kill her hogs or set her fields aflame, and her obligation to make yearly payments of rum and powder to them. After William Penn (1644-1718) surrendered his claim to Shackamaxon Island in a 1684 patent issued to Thomas Fairman (c. 1650-1714), whom Kinsey married in 1680, map-makers and land owners referred to it as “Fairman’s Island.”

Fairman’s Island was part of Pennsylvania and a point of connection between the new province and West Jersey. From 1681 to 1683 Quakers crossed the Delaware for their monthly meetings, alternating between the homes of the Fairmans at Shackamaxon and William Cooper (1632-1710) at Pyne Poynt (later part of Camden) on the opposite shore. The island was a landmark for Delaware River boat travelers. Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) encountered it on his first trip to Philadelphia in 1723. Starting late from Burlington, New Jersey, on a cold windless October evening, he and his company rowed south until midnight and, not seeing the city’s lights, put to shore and made a fire. At daylight they discovered they had spent the night in Cooper’s Creek a little north of Philadelphia, which they saw as soon as they rowed out of the creek and passed the island.

Agriculture prevailed on the island during the eighteenth century as it gained a new name, Petty Island, from Philadelphia merchant John Petty (1702-63), who bought it in 1732. When Petty advertised the 300-acre island for sale in 1741 as a whole or in lots, he described forty acres of meadow, thirty acres cleared for corn, grain, or tobacco, an orchard of peach and apple trees, and a frame house with two brick chimneys. In 1760 he sold his last parcel (forty acres) to Joseph Cooper (1735-1818), who continued agricultural uses and purchased most of the other parcels. While slaves probably worked in the fields or maintained banks and sluices on the island, the only evidence for its possible use as a slave depot or offloading point is indirect. John L. Morrison’s Romance of Petty’s Island (1917) cited testimony before the Board of Trade and Plantations in London in the 1760s that a Mr. Pemberton landed a cargo of slaves on the north end of the island and later in Jersey “privately” to avoid the protective tariff duty Philadelphia charged on human chattels.

Two States Divide the Islands

Following the American Revolution, New Jersey and Pennsylvania formed a compact to divide the Delaware River islands. Joseph Cooper served as one of New Jersey’s three boundary commissioners who, with their Pennsylvania counterparts, agreed in 1783 that Petty Island would become part of New Jersey. By 1851 the island was home to several small farms and eighteen families.

As economic development and competition for suitable riverfront land intensified in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania ship-builders and other proprietors built wharves, docks, warehouses, and workers’ housing opposite their existing operations. In 1852 Andrew (1806-92) and James (1812-86) Manderson purchased two large tracts to expand their Philadelphia-based lumber business and operate a farm. They gave the island a new name, Treaty Island, to honor the treaty Penn made with the Lenape at the Fairmans’s Shackamaxon home in 1683. (Treaty Island appeared on many local maps up to 1990, although the U.S. Guard and Geodetic Survey maps retained the name Petty Island.) William Cramp (1807-79) also expanded his shipyard to the island, where it built a variety of vessels, including the clipper ship Manitou (1855). For a few years in the 1880s, a dancing and drinking resort called “Willow Grove” also drew recreational visitors.

Shipbuilding-related activity continued until 1893 when the Army Corps of Engineers, after using eminent domain to acquire and demolish most of the island’s commercial activity and infrastructure, cut the island’s western shoreline and dredged away 150 acres. This action was the last stage of a massive redevelopment of Philadelphia’s port, which included removing Smith’s and Windmill Islands downriver, deepening and widening the Delaware’s channel, and extending the Philadelphia wharf line farther into the river to accommodate larger vessels. To direct the river’s current toward the Philadelphia shoreline to maintain the new channel depth, Army engineers removed Petty Island’s broad southwest point opposite Cooper’s Point to make the island conform to the bend in the river and reshaped the southern end into a sharp jetty pointing downriver.

During the twentieth century, industrial usage reigned, including storage and refining of petroleum products. The first oil company to take an interest in Petty Island, Crew Levick Company of Philadelphia, purchased fifty acres in 1916, the same year it was acquired by Cities Service, a holding company based in Oklahoma. In the early 1930s Cities Service’s oil island refinery and tank farm, which had 21 million gallons of storage capacity, made Camden one of the most important ports on the Atlantic seaboard for oil-burning ships. In 1931 thirty-one oil tankers brought crude oil to the island for refining and more than 5,000 rail cars departed the island with product for delivery to customers. The southern tip of the island also became a coal yard to serve electric power stations of the Philadelphia Electric Company from the early 1920s into the early 1930s. Cramp Shipbuilding returned to the island from 1919 to 1927 and again in 1939 to meet expanding shipbuilding demands for World Wars I and II. By 1953, however, Cities Service (rebranded CITGO in 1965) had sole ownership of the island. Under lease from CITGO, beginning in 1980 the former coal yard of Philadelphia Electric became a cargo marine terminal built and operated by California-based Crowley Maritime Corporation.

Nesting Eagles Affect the Island’s Fate

New options emerged in the early years of the twenty-first century. Seeking to increase its tax base, in 2004 Pennsauken Township, New Jersey, approved a plan to use eminent domain to acquire the island, clean it up, and redevelop it as a high-end housing complex, hotel, conference center, and golf course. CITGO, which was initially receptive to participating in the island’s redevelopment, reversed course after it discovered a rare pair of American bald eagles nesting on the island and other threatened wildlife in June 2002. CITGO concluded that the nest would significantly limit development. In addition, the company would be exposed to high costs for island clean up and restoration if another developer controlled the pace, method, and extent of cleanup contaminated soil and groundwater. CITGO instead offered to donate the island to New Jersey for a wildlife reserve for free.

Although a majority on the New Jersey Natural Lands Trust voted in 2004 to accept the donation, the state rejected the gift amid political pressure from local and state officials who favored development. The rejection of that proposal gave rise to an unusual four-year alliance between CITGO and New Jersey’s major environmental groups, who formed the Save Petty’s Island Coalition to advocate for a wildlife reserve.

The Coalition’s public relations campaign to persuade New Jersey to reconsider CITGO’s donation was aided by a series of events over the next four years. New Jersey’s attorney general indicted Pennsauken’s developer (Cherokee) for causing the death of an endangered Petty Island eagle. Attorneys for Camden City residents, whose homes were designated for taking by eminent domain in a related Cherokee redevelopment project, obtained a court order invalidating Cherokee’s plans. State officials declined to approve a novel tax increment financing plan for Cherokee’s Meadowlands landfill redevelopment project which subsequently declared bankruptcy. In the wake of these controversies, Pennsauken and Cherokee let their waterfront redevelopment agreement expire in March 2008 after Cherokee wrote “it is difficult to obtain private financing for construction and development.”

In January 2009, through its Natural Lands Trust, New Jersey accepted CITGO’s offer to clean up and make Petty’s Island a state urban wildlife preserve by 2020. It also accepted CITGO’s offer of $3 million to help manage island access and construct an interpretive visitor center. In 2011, more than $900,000 in remediation projects funded by CITGO included shoreline oil boom maintenance, disposal, groundwater remediation, and excavation and disposal of contaminated materials. Plans called for restoring the island’s forest and wetlands and creating a grassland habitat in the center. CITGO’s agreement with the Natural Lands Trust provided that the island would be turned over to the Natural Lands Trust no later than 2020, setting the stage for a new chapter in the history of Petty Island.

Robert A. Shinn received his master’s degree in political science in 1972 and bachelor’s degree in American civilization in 1970 from Brown University. He serves as treasurer of the Camden County Historical Society and conducts historical research and tours of Petty’s Island for the New Jersey State Natural Lands Trust. With Kevin Cook, he authored Along the Cooper River: Camden to Haddonfield (Arcadia Publishing, 2014).

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Petty's Island Preserve (New Jersey Natural Lands Trust)

- Petty's Island Preserve (New Jersey Audubon Society)

- Focusing on the Petty (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Petty Island - Timeline of its History (PDF, New Jersey Audubon Society)

- Petty's Island: Wayside Exhibits and Photographs of Some Existing Structures (New Jersey Natural Lands Trust)

- Penn Treaty Museum

- Petty Island: A Sacred Part of our Nation's History (YouTube)

- Petty's Island (Independence Hall Association)

- Reclaiming the Lost Kingdom of Laird (Duke Riley)

- Reclaiming the Lost Kingdom of Laird (Vimeo)

- Cramp Ship Building Company Collection (PDF, Independence Seaport Museum)