Philadelphia Negro (The)

By Steven McGrail | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

In 1899, the University of Pennsylvania published The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study, the first scholarly race study of an urban place in what became a growing trend of Progressive-era social surveys. The massive report about Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward became a distinctive (and still relevant) landmark in the annals of sociological study and social advocacy.

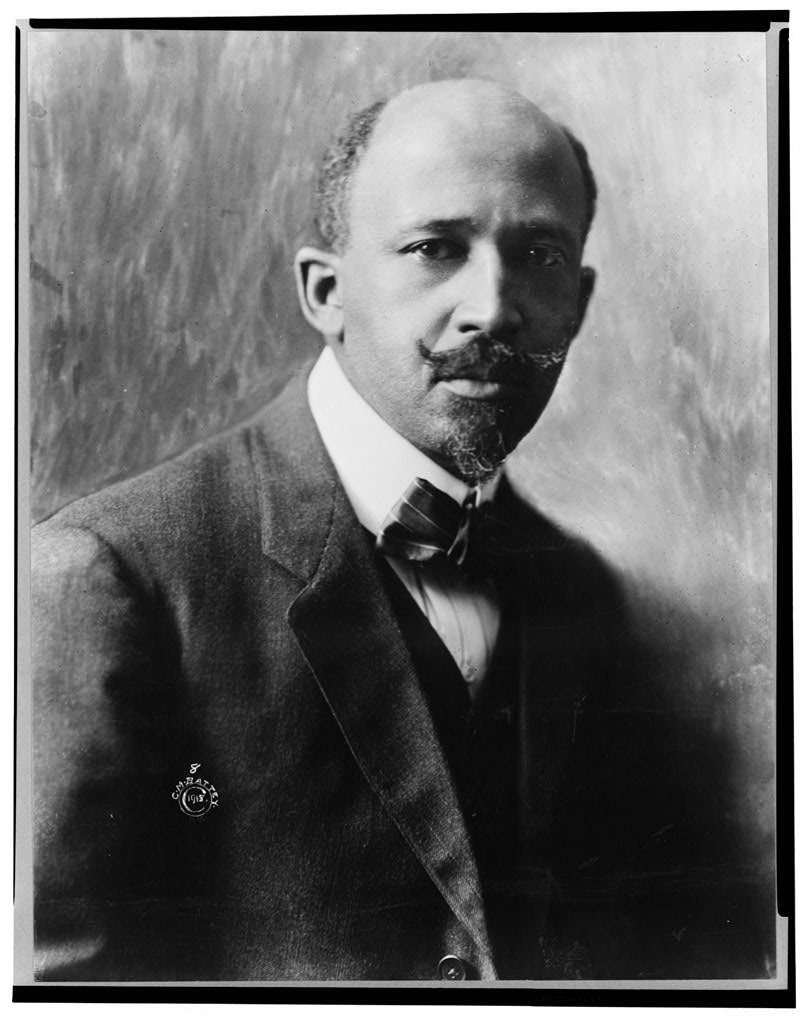

Four years earlier, the publication of Hull-House Maps and Papers (1895)—a pioneering local study of immigrant, labor, and living conditions in and about the Chicago settlement run by Jane Addams—signaled opportunity in the minds of Philadelphia progressives. In spring 1896, at the suggestion of leading citizen Susan P. Wharton, the University of Pennsylvania and Philadelphia’s own College Settlement sent for the rising African American scholar William E. Burghardt Du Bois (1868-1963), then a professor at Ohio’s Wilberforce University, to conduct a study of the city’s black community, which many critics held responsible for a post-depression (1893-96) rise in crime and disorder. Accepting the invitation, even at the lowly title of “Assistant Instructor,” Du Bois began in August 1896 to “ascertain something of the geographical distribution of this race, their occupations and daily life, their homes, their organizations and, above all, their relation to their million white fellow-citizens.” The massive report that followed went far beyond the Hull-House model, and far beyond what its patrons anticipated or perhaps desired.

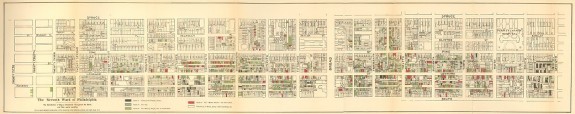

Despite its title, The Philadelphia Negro’s subject was both larger and smaller than the term “Philadelphia” connotes. It is really a neighborhood study, focusing on the central Seventh Ward running north-south from Spruce to South Street and east-west from Seventh Street to the Schuylkill River. Site of the city’s oldest African-American community, dating to the colonial era, the Seventh Ward by the 1890s was home to nearly a quarter (roughly 9,700) of Philadelphia’s 40,000 blacks (the largest such population in any northern city). Incredibly diverse, the ward mingled affluent whites (including Wharton) on its western fringe, one of the nation’s densest concentrations of black elites at its center, along Lombard Street (west of 9th), and multitudes of the poor of both races on the ward’s eastern front, where lay the city’s most notorious black ghetto.

Du Bois Lived in Seventh Ward

For more than a year (1896-97) Du Bois and his wife resided within the poorer quarters surrounding College Settlement on Saint Mary Street. To many Seventh Ward blacks, the Harvard- and Heidelberg-educated Du Bois looked the part of his genteel sponsors, who hoped to use his analysis to justify sweeping reforms in the black community. Du Bois, meanwhile, preferred to demonstrate that blacks possessed their own internal class structure and should not be judged solely by the lowest rung (the “submerged tenth”). Likewise, the imagined “Negro problem,” he argued, was “not one problem, but rather a plexus of social problems” having less to do with a monolithic black “social pathology” than with whites’ enforcement of racial discrimination and provision of unequal opportunity.

Pioneering sociological methods, Du Bois and his lone appointed assistant (College Settlement’s Isabel Eaton, who herself published a trail-blazing study of domestic labor as an appendix to the larger work) employed archival research, descriptive statistics, and questionnaires compassing occupations, health, and education as well as religious, social, and family life. Most crucially, they conducted a door-to-door canvass of the ward, amassing over 5,000 personal interviews. The findings revealed a heterogeneous and accomplished community, a portion of which affirmed the reality of poverty, crime, and illiteracy. Addressing this imbalance, Du Bois emphasized socioeconomic and historical causes, notably the exclusion of blacks from the city’s premier industrial jobs and single-family homes and the formidable legacy of slavery and checkered race relations.

In stressing circumstance and contingency, Du Bois demonstrated structural inequities of which many whites were largely unaware, in the process leveling a powerful rejoinder to then prevalent arguments that used race theory, evolutionary science, and scriptural interpretation to justify discrimination. Du Bois hoped this work would be supplemented by similar studies of other cities, yet what began as a local study came, by default, to stand for all of urban Black America. Most of Du Bois’s methods lay dormant, re-emerging only in the 1920s—in Chicago again, with the rise of the Chicago School of Sociology. A fair hearing for his forthright and formidable conclusions, meanwhile, waited longer still. Du Bois’s study has enjoyed a renaissance in contemporary scholars’ investigations of poverty, race, and political economy, and The Philadelphia Negro continues to inform readers with its poignant representation of one of the great forgotten communities in modern American history, whose vitality, diversity, and challenges still linger in its pages.

Steven McGrail, Ph.D. Candidate in U.S. History, Rutgers University – New Brunswick, specialty: cultural history and national identity; advisors: Jackson Lears, David Foglesong, Ann Fabian.

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.