Philadelphia Orchestra

Essay

Founded in 1900, the Philadelphia Orchestra developed into an iconic organization for Philadelphia through its musicianship, commitment to culture and education, and service as a cultural ambassador. The musical tastes and personalities of a series of influential conductors infused the orchestra with a rich history and distinctive sound as it became one of the finest and most renowned orchestras in the world.

Philadelphia did not have an orchestra to call its own until late in the nineteenth century, despite a long history of musical performances sponsored at venues such as Musical Fund Hall (opened in 1824) and the Academy of Music (1857). The first step toward creating a Philadelphia-based orchestra came in 1893, when opera conductor Gustav Hinrichs (1850-1942), choral director Henry Gordon Thunder (1865-1958), and composer William Gilchrist (1846-1916, founder and conductor of the city’s Mendelssohn Club) founded the Philadelphia Symphony Society and began producing three amateur concerts a year at the Academy of Music. In 1899, the society hired Fritz Scheel (1852-1907) to conduct not only the three amateur concerts but also two concerts in spring 1900 with professional musicians recruited from around the city. The success of these concerts laid the groundwork for forming the Philadelphia Orchestra.

An executive committee led by Henry Whelen Jr. (1848-1907), a well-known patron of music and the arts in Philadelphia, announced a plan to begin the Philadelphia Orchestra with a season of six concerts during 1900-01. While expecting to cover costs through ticket sales, the committee also sought to raise a guarantors’ fund of $10,000 and exceeded that goal by $5,000.

Under the baton of Fritz Scheel, the orchestra performed its inaugural concert at the Academy of Music on Friday, November 16, 1900. The concert, which received all positive reviews, featured Russian-born Ossip Gabrilowitsch (1878-1936) as piano soloist and a program of European classical music: Carl Goldmark’s Overture In Spring, op. 36, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in C minor, op. 67, Tchaikovsky’s Concerto for Piano No. 1 in B-flat minor, op.23, Carl Maria von Weber’s Invitation to the Dance, op. 65, and Wagner’s “Entry of the Gods in Valhalla,” from Das Rheingold.

Concerts Beyond Philadelphia

The success of the orchestra’s inaugural season spurred its patrons to create the Philadelphia Orchestra Association, formed on May 17, 1901, and consisting of officers, a board of directors, and executive committee. Scheel became the orchestra’s first official music director and conductor, and he realized almost immediately that the orchestra could not be sustained by local concerts alone. In the first year the musicians traveled only within the immediate region in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, but in the second season, despite a large deficit, the orchestra managed to travel to New York, Baltimore, and Washington.

Scheel’s term as conductor and musical director spanned the early challenges, financial difficulties, and successes of the orchestra, and his legacy laid the foundation for his successors. Scheel searched for and hired the finest musicians, invited well-known guest artists, and performed works by the great European masters as well as lesser-known composers. His death on March 13, 1907—from pneumonia contributed by nervous exhaustion—was mourned as a great personal loss to the orchestra and to Philadelphia.

Bohemian-born Karl Pohlig (1864-1928) succeeded Scheel and enlarged the orchestra from sixty-five players to eighty. He expanded the orchestra’s repertoire and invited the Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) to guest conduct in 1909. However, orchestra musicians found him abrasive, and a soloist described his conducting as “uninspired.” Pohlig’s tenure ended abruptly with the revelation of an extra-marital affair with his secretary.

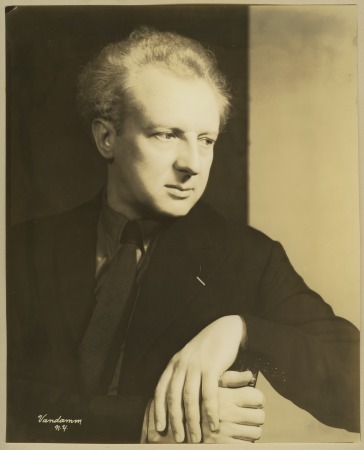

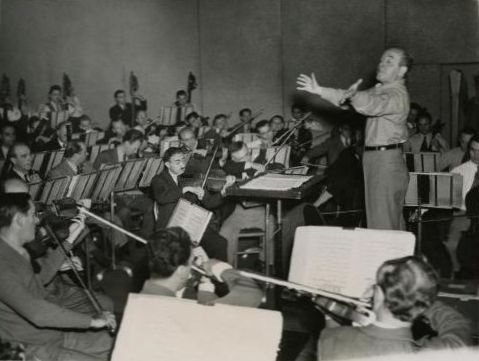

Leopold Stokowski (1882-1977), previously conductor of the Cincinnati Orchestra, became the orchestra’s third music director in 1912. Imposing his own set of performance standards, Stokowski fired thirty-two musicians in the first year and for the next decade focused on replacing players with the finest professionals. His preference for a less rigid performance style, including “free bowing” for string players, created the warmer, more intense and continuous sound that became the hallmark of the Philadelphia Orchestra, known as the “Philadelphia Sound.”

Stokowski Triumphs

Stokowski conducted his first concerts in Philadelphia on October 11 and 12, 1912, with a program consisting of Beethoven’s Overture to Leonore, no. 3, Brahms’ Symphony no. 1 in C minor, op. 68, Michael Ippolitow-Iwanow’s “Sketches from the Caucasus,” and Wagner’s Overture to Tannhauser. He scored his first major triumph with the American premiere of Mahler’s Eighth Symphony in 1916. It was a massive undertaking, including three performances with three choruses (950 voices), 110 players in the orchestra, and eight soloists. Hugely successful, these concerts were hailed by the directors of the Philadelphia Orchestra Association as marking nothing less than “an epoch in the musical history of Philadelphia to which no other event is comparable.”

Stokowski and the orchestra further enhanced the orchestra’s reputation by making recordings for more than thirty years with Camden’s Victor Talking Machine Company and RCA. Stokowski’s legacy also included children’s concerts, which began in 1921 for children ages twelve and under and evolved in 1933 into a series of hugely successful youth concerts. Moreover, Stokowski’s attraction to film had opportunities for an even wider audience. Stokowski inspired Walt Disney (1901-66) to create the full-length animated film, Fantasia in 1940, which featured classical music and the Philadelphia Orchestra. The film was successful but did not lead to additional collaborations.

The Philadelphia Sound continued under the baton of its fourth music director, Eugene Ormandy (1899-1985), who held the position for more than four decades. Between 1940 and 1970, Ormandy enhanced the Philadelphia Sound by purchasing the finest string instruments by makers such as Stradivari and Guarneri. The instruments, combined with the extraordinary talent of the string players, further established the Philadelphia Orchestra’s reputation as the finest in the world. The musicians’ many travels with Ormandy included a 1949 tour of Great Britain, the orchestra’s first tour of continental Europe in 1955, performing twenty-eight concerts in eleven countries, and in 1973, a tour to the People’s Republic of China, a first for an American orchestra.

Along with musical successes, Ormandy and the music directors who followed him in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century faced numerous institutional challenges, including labor relations with musicians. Strikes or threats of strikes by members of the orchestra centered on wages, pensions, health care, and parity of salaries with other orchestras. The first major strike by the musicians’ union—the Philadelphia Musical Society, Local 77, of the American Federation of Musicians—occurred in 1966 during Ormandy’s tenure and lasted fifty-eight days. The second, in 1996, was caused by several factors and lasted sixty-four days. The orchestra musicians blamed the management for the delay in the building of a new concert hall, for a three-year deficit that led to pay and healthcare concessions to balance the budget, and more importantly, the loss of a recording contract with EMI, which had expired in August 1996. While under a recording contract, the musicians were guaranteed a minimum sum above their salary through broadcasting and recording fees. Musicians feared the loss of the contract would not only erode the orchestra’s national media exposure, but also would prevent the orchestra from attracting first-rate musicians and diminish its reputation as one of the best orchestras in the world.

Muti, Sawallisch, Eschenbach

While Ormandy continued the orchestra’s lush sound and standard nineteenth-century repertoire, his successors instituted many changes. The next music director, Riccardo Muti (b. 1941), who led the orchestra from 1980 to 1992, programmed a range of music from Haydn to Penderecki and introduced a leaner sound, criticized by many. Wolfgang Sawallisch (1923-2013), who followed in 1993, brought back the Philadelphia Sound and favored works by Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Schumann, Bruckner, Dvorak, Brahms, Wagner, and Strauss. He also introduced more American music and modern works. As senior musicians retired, Sawallisch reshaped the orchestra by replacing more than a third of the players. His successor, Christoph Eschenbach (b. 1940), increased community outreach and regularly performed chamber music with members of the orchestra as a pianist. However, in 2008 he announced his tenure with the orchestra would end amid negative comments in the press in Philadelphia, which arose partly from orchestra members unhappy about the initial hiring process of Eschenbach and later by his style as a leader.

The most significant change for the orchestra during this period was its move to a new home, the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, where Sawallisch conducted the inaugural concert in Verizon Hall on Saturday, December 15, 2001. The program consisted of Kernis’ Color Wheel, Ravel’s Daphis et Chloé, and Beethoven’s Triple Concerto in C Major, Op. 56, with performances by Emanuel Ax (b. 1949), Itzhak Perlman (b. 1945), and Yo-Yo Ma (b. 1955). Verizon Hall proved to be different acoustically from the Academy of Music. Its vastness produced a more brilliant sound, and for the first time players could hear each orchestra section clearly. As a consequence, the performers had to learn how to blend and play differently.

The orchestra also made changes to attract new audiences. Some were minor, such as giving up the formal wear “uniform” worn by the players and having the orchestra stand up and acknowledge the audience. In an attempt to fill the hall and persuade more people to give the orchestra a chance, inexpensive tickets were made available one half hour before concert time and students of the Curtis Institute of Music were admitted free just as a concert was about to begin. The orchestra also began outdoor performances in neighborhoods throughout the city. Other, more major, adjustments included adding visuals in the form of slides, dancers, dramatic readings, and even circus acts to accompany familiar and unfamiliar music. The orchestra also continued to play in venues such as the Mann Center for the Performing Arts and Saratoga (N.Y.) Performing Arts Center to attract audiences who were generally non-concert goers.

Nézet-Séguin Debuts

During this period of turmoil and change, Yannick Nézet-Séguin (b. 1975), a Canadian born prize-winning pianist and conductor, emerged as the next music director following an interim of four years in which Charles Dutoit (b. 1936) became chief conductor. Nézet-Séguin debuted as guest conductor in December 2008, became music director-designate in June 2010, and then music director in 2012. In January 2015, the orchestra extended Nézet-Séguin’s contract to the 2021-22 season.

Nézet-Séguin’s ascent to the podium occurred as the Philadelphia Orchestra Association declared and emerged from bankruptcy. The financial woes that led to the 2011 declaration of bankruptcy—the first for an American orchestra—included the high cost of musicians’ pensions and financial obligations to Grammy-winning pianist and Philly Pops artistic director Peter Nero (b. 1934). The orchestra also faced renegotiating agreements with the owners of the Kimmel Center and a new collective bargaining agreement with musicians. The Orchestra Association came out of bankruptcy in June 2013, but not without deep concessions by its musicians.

Rising above the fray of the bankruptcy turmoil, Nézet-Séguin focused his energy on music and audiences, including some risk-taking in programming by introducing more Baroque music, more vocal music, and more contemporary American composers. Nézet-Séguin’s youthful exuberance and musicianship opened a new era of seeking larger audiences and while continuing the legacy of the Philadelphia Orchestra.

Joseph C. Schiavo is a Clinical Associate Professor of Music and the Associate Dean for Undergraduate Programs and University College in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Rutgers University–Camden.

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Philadelphia Orchestra going to China in 2012 (NewsWorks, September 23, 2011)

- New era begins for Philadelphia Orchestra (NewsWorks, January 25, 2012)

- Philadelphia Orchestra fashions relationship with new music director (NewsWorks, October 22, 2012)

- After nearly three decades, a final 'Feast of Carols' for Mendelssohn Club director (NewsWorks, December 12, 2014)

- Philadelphia Orchestra scores with classic Philly sport moments (NewsWorks, July 23, 2013)

- A secret language inspires music performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra (NewsWorks, October 31, 2013)

- Former Philadelphia Orchestra Sawallisch conductor dies (NewsWorks, February 25, 2013)

- Philadelphia Orchestra's final Asian tour to include live broadcasts (NewsWorks, May 13, 2016)

- A musical passage to NYC for Nézet-Séguin--while still leading the Fabulous Philadelphians (NewsWorks, June 2, 2016)

- After weekend walkout, Philadelphia Orchestra offers fans bouquet of pop-up concerts (NewsWorks, October 3, 2016)

- Philadelphia basement birthed iconic ‘Fantasia’ sound (NewsWorks, October 13, 2016)

- Philly Orchestra sues for unpaid $70K bill from papal performances (NewsWorks, October 27, 2016)

- With $2.5 M, seeking to discover Philly's next classical generation (NewsWorks, June 15, 2017)

- CEO of Philadelphia Orchestra to step down in December (NewsWorks, June 20, 2017)

- Philadelphia Orchestra begins European tour, including first stop in Israel in 25 years (WHYY, May 22, 2018)

- Philadelphia Orchestra has a new collaborator: artificial intelligence (WHYY, April 9, 2022)

- The history of the Philadelphia Orchestra now lives at Penn (WHYY, December 11, 2022)

Links

- Philadelphia Orchestra

- Philadelphia Orchestra YouTube Channel

- Yannick Interview: 2015-16 Mahler's Eighth Symphony

- Philadelphia Orchestra Highlights from Tour History (PhilOrch.org)

- Leopold Stokowski and the Victor Talking Machine Company (Stokowski.org)

- The Victor Talking Machine Company (The David Sarnoff Library)

- Philadelphia Orchestra’s 2016-17 Season Highlights Diversity of Sound (Philadelphia Magazine, January 20, 2016)

- At The Academy, The Birth Of Wire Transmission Of Music (Hidden City Philadelphia, April 30, 2013)

- 'Philadelphia Sound' Faces a Test of Time (New York Times, November 14, 2000)

- EUGENE ORMANDY IS DEAD AT 85 IN PHILADELPHIA (New York Times, March 13, 1985)

- Philadelphia Gets A New Concert Hall A Century Aborning (New York Times, December 9, 2001)

- What Does a Conductor Actually Do?