Recording Industry

Essay

The birthplace of the American “record” industry, the Philadelphia region for more than a century has been home to a thriving industry of recording studios and record companies. In Camden, New Jersey, the Victor Company in the early 1900s was the nation’s largest manufacturer of musical recordings. Since then, Philadelphia’s unique concentration of diversified industries, entrepreneurship, and the musical creativity of its ethnically and racially diverse communities has produced new iterations of a unique Philadelphia “sound” that has had national and international appeal.

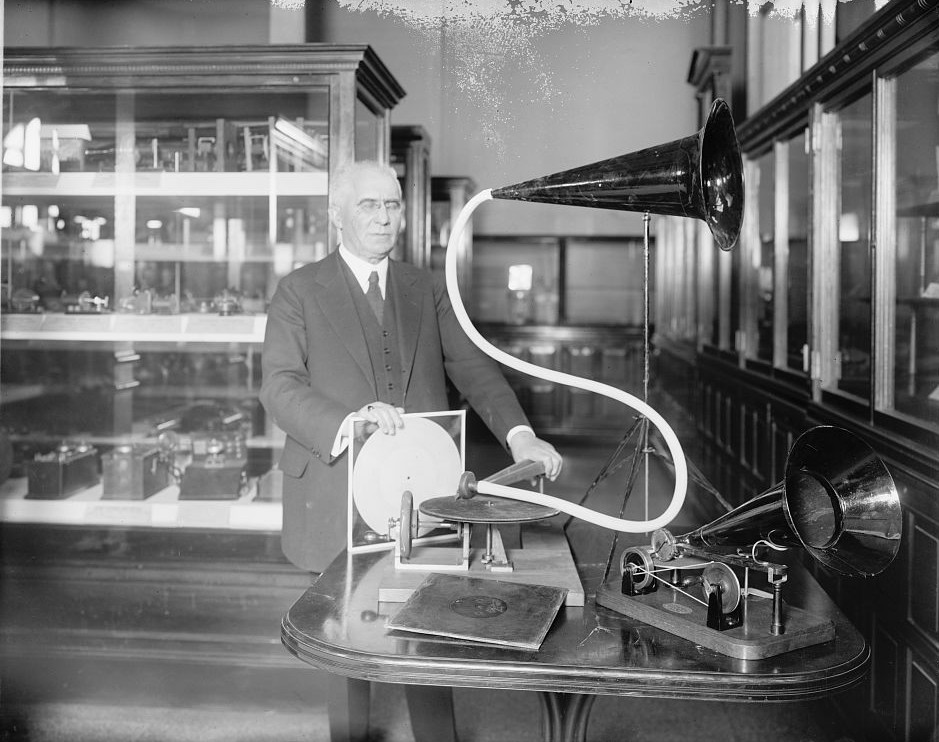

On May 16, 1886, Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute hosted the first public lecture and demonstration of the newly patented “Gramophone” in its old gray stone building on South Seventh Street (later the home of the Philadelphia History Museum). Before an assembly of some four hundred men and women, inventor Emile Berliner (1851-1929) presented a history of recorded sound and explained how his new mechanism for “etching the human voice” on a horizontal disc improved upon the vertically-inscribed “Phonograph” patented by Thomas Edison in 1878.

After his Philadelphia unveiling Berliner, based in Washington, D.C., worked on technical improvements to his “phonautograph” and incorporated the United States Gramophone Company. His venture floundered, however, until a group of Philadelphia investors provided a life-saving infusion of new capital and formed the Berliner Gramophone Company in 1895.

Recording Competition

The company faced a steep challenge. The Edison Company’s higher fidelity cylinders had a longer playing time and a spring-driven motor that kept the stylus moving at a constant speed. Berliner’s horizontal discs, however, had critical advantages. Most importantly, Berliner discs, unlike the Edison cylinders, which were each a unique recording, could be mass-produced from a single master disc. Needing a mechanism to replace the hand-driven crank that powered the original gramophone turntable, Berliner ordered about two hundred small, inexpensive, hand-wound spring motors made by Eldridge Johnson (1867-1945), who ran a small machine shop just across the Delaware River in Camden.

The Berliner Gramophone Company set up its first offices at 424 S. Tenth Street in Philadelphia (on the corner of Lombard Street), set up a makeshift factory for production of gramophones at 1026-28 Filbert Street and a recording studio, and in 1897 opened a retail salesroom—the nation’s first record store—at 1237 Chestnut Street.

An avid amateur musician and composer, Berliner focused from the start on “canned music” for the home entertainment market. At its Philadelphia recording studio, the Berliner Company began to record what biographer Frederic William Wile called “the whole gamut of audible phenomena,” including John Philip Sousa’s Famous Band, the most popular American musical ensemble of the era. Berliner rounded out the catalogue with recordings of the U.S. Marine Band; band musician solos; orchestral pieces; comic, “coon songs” (popular music with Black stereotypes); German, and Italian songs; Negro shouts; recitations, both serious and humorous; and the world’s first operatic recording on disc, “La Donna e Mobile” and “Quest o Quella,” sung by Philadelphia tenor Ferruchio Giannini.

By 1898 Gramophone and disc sales were soaring. Patent suits and financial struggles, however, forced the Berliner Gramophone Company into receivership. In 1900, Johnson, who already was manufacturing gramophones and improving both the gramophone and the disc recording process, bought the Berliner patents and formed his own company.

Victor Talking Machine

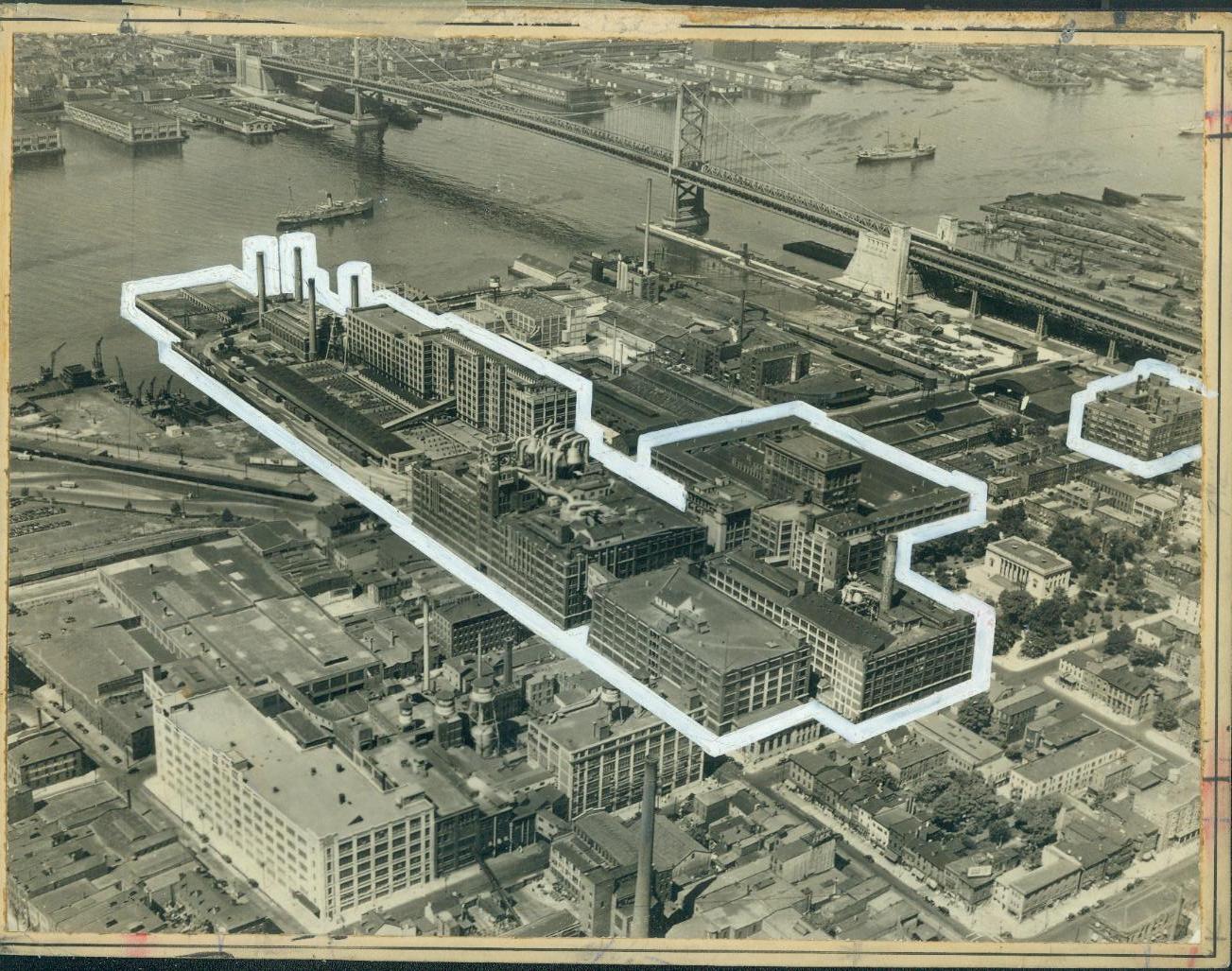

In 1901 Johnson incorporated the Victor Talking Machine Company, moved his small Camden recording studio to the second floor of the old Berliner offices at 420 S. Tenth Street in Philadelphia, and constructed a matrix-plating plant in the building’s basement. Making shrewd use of advertising under the Berliner “His Master’s Voice” logo for national branding, Victor built sales, and prestige, by releasing recordings of international celebrities from the world of classical music on its Red Label records, introduced in 1902. Victor opened its own pressing plant in Camden in 1905, and the next year introduced the “Victrola,” the first consumer record player with an internal horn and record storage space.

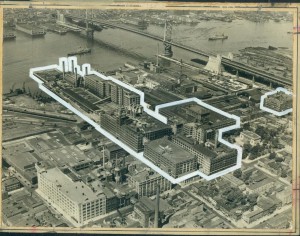

To meet soaring consumer demand, the Camden plant exploded in size. By 1915, it included the world’s largest talking-machine and record factories. In the 1920s more than 13,000 men and women manufactured records and Victrolas on a sprawling fifty-one acre physical plant that included thirty-eight buildings with 2,534,000 feet of floor space. Its sixteen-acre lumber yard held what one industry writer called “probably the most valuable stock of selected hardwood lumber ever gathered.” Victor’s massive and ever-growing catalogue of recordings included country and ethnic music, jazz and dance music, spoken word, race records, show tunes, and more.

The presence of the world’s largest record label in Camden proved a boon for Philadelphia-area musicians and ensembles. In the 1910s Victor cemented a close relationship with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Its conductor, Leopold Stokowski, worked closely with Victor engineers to produce orchestral recordings of unparalleled clarity, recording first in the Executive Building in Camden and then in Trinity Church on North Fifth Street.

Close proximity to the Victor studios also provided Philadelphia musicians and singers opportunities for session work and other recordings. In 1923 Victor presented a young Marian Anderson singing the African American spiritual “Deep River,” five years before her first Carnegie Hall Recital. With a rich musical heritage and multicultural population, Philadelphians produced popular music with broad appeal. Ethel Waters’ clear northern diction and refined vocal style enabled her to become one of the first stars for Black Swan in New York, the nation’s first back-owned record company. Jazz greats Charlie Gaines, Joe Venuti, and Eddie Lang, and bandleaders Howard and Sam Lanin all developed their sounds in Philadelphia. In the 1920s Sam Lanin carried the Philadelphia style of “society”-based popular music to New York, where he became a major band broker for dozens of record companies.

Commercial Radio Emerges

In the 1920s the emergence of commercial radio created new challenges and opportunities for the live music and recording industries. Philadelphia quickly became a center of radio manufacturing, its Atwater Kent Company producing as many as one-third of the radios sold in 1927-28. For a while the popularity of radio drove down record sales, but radio broadcasts also carried Philadelphia-based musicians and ensembles to new audiences. It also forced Victor to innovate.

After record sales plummeted in 1924, Victor secured patents from Western Electric for a new, electrical method of recording and made its own first electrical recording, of the 37th annual Mask and Wig Club production, on location in Philadelphia. Victor then opened a large studio in Building 15, where in 1925 it produced its first electrical orchestral recordings, with the Philadelphia Orchestra (Saint Saens’ Danse Macabre).

Record sales soared to a new high of 104 million discs in 1927. Two years later, RCA purchased the company and retooled its sprawling Camden plant for the manufacture of radios. In the decades that followed, RCA’s Camden complex played important roles in the development of radio, stereophonic sound recording, and television.

Technological innovations, sustained economic prosperity, and the coming of age of American mass consumer culture drove a new transformation of the American recording industry in the decades following the end of World War II. Both analog open-reel audiotape and recorders brought over from Germany at the end of the war and improving vacuum tube technology increased fidelity, drove down the cost of sound recording, and gave rise to new, small recording studios. The introduction of the 12-inch Long Playing (LP) vinyl disk by Columbia in 1948 and the smaller and less expensive 7-inch 45 rpm vinyl disc by RCA Victor in 1949 enabled small pressing plants to manufacture (and small labels to release) records for niche markets. In post-war Philadelphia these upstart recording studios and labels grew by recording and selling the sounds of the city’s vibrant subcultures of jazz, doo-wop, and rhythm & blues.

Bandstand and Teenage Consumers

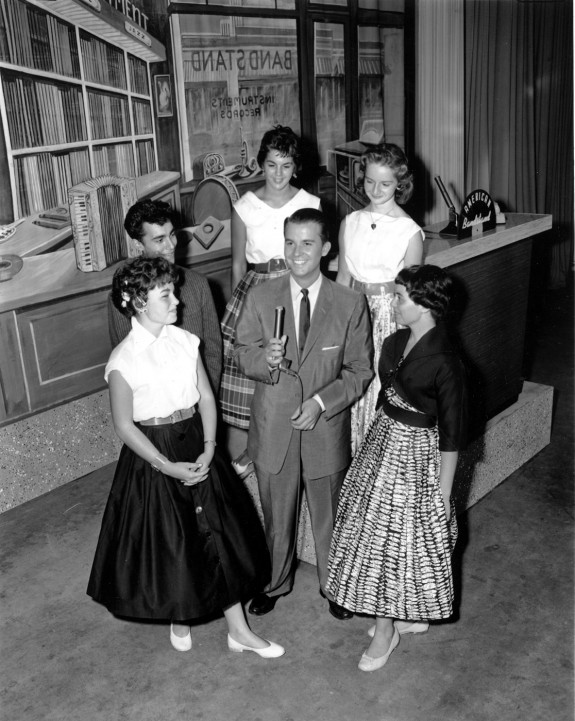

In the 1950s, Philadelphia emerged as a “break-out” market for records appealing to local and national teenage consumers. Close enough to New York and large enough to have some of the Big Apple’s energy, newness, and ethnic and racial diversity, the city was also distant and conservative enough to be more closely attuned to the tastes and culture of American mainstream audiences. And here, in 1952, WFIL debuted Bandstand, which brought not just the sound, but also the dances and look of young Philadelphians, many of them high school students from the city’s ethnic neighborhoods, to a regional television audience.

By featuring local performers, Bandstand drove up the record sales of new labels, the most successful of which was Cameo Parkway. Founded in 1956, by bandleader turned songwriter Bernie Lowe, Cameo, recording in its own studios in the Schubert Building on South Broad Street, released a string of hits by Bobby Rydell, the Orlons, and Dee Dee Sharpe, all products of the local Philadelphia music scene. First appearing on the Cameo’s subsidiary Parkway label in 1960, Chubby Checker performed “The Twist”, launching an international dance craze. Cameo Parkway followed this up with the Dovells’ “The Bristol Stomp” and “Hully Gully.” In the early 1960s Cameo Parkway was the hottest independent label in the country. At the same time, Singular, Swan (1957-65), Chancellor (1957-64), and other Philadelphia labels turned out records by the dozens that, when pushed by local djs and played at local record, or “sock hop,” dance parties, could quickly sell 50,00-60,000 copies.

From 1957, when it began national broadcasts, until it moved to Los Angeles in 1963, American Bandstand (1952-89) carried the highly produced and orchestrated “Philadelphia Sound” across the nation and made stars of “teen idols” Bobby Rydell, Frankie Avalon, and Fabian. Before closing its doors in 1968, Cameo’s releases also included albums by Maynard Ferguson, Clark Terry, and other jazz greats, and singles by the Kinks, Bob Seger, and the Ohio Express.

The Philadelphia Sound

The Philadelphia Sound, however, proved short-lived. In the early 1960s consumer dollars moved to the Motown sound coming out of Detroit, and then the British invasion, and psychedelic rock. Simultaneously, however, a new musical scene was emerging in Philadelphia, with its own small, low-budget recording studios, start-up labels, and songwriters and producers, who would help shape the next iteration of the “Philadelphia Sound.”

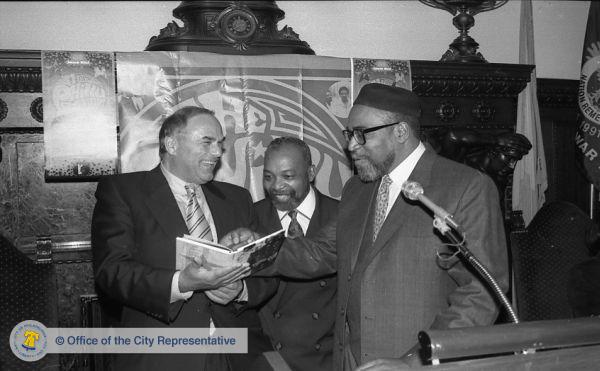

To compete with Motown’s extraordinary success in marketing Black soul music to national audiences, Atlantic Records in New York and other major labels sought out three young Philadelphia-based songwriter/producers, Leon Huff (b. 1943), Kenny Gamble (b. 1942), and Thom Bell (1943-2022), who produced soul records for them at the new state-of-the-art Sigma Sound Studio on 212 N. Twelfth Street, founded by former Parkway Cameo engineer Joe Tarsia in 1968. In 1970 Columbia Records in New York created a separate soul music division, then signed an exclusive production agreement with Gamble and Huff in 1971 to write and produce records released on their own Philadelphia International Records label. Recording at Sigma Sound, Philadelphia International Records produced a string of hits with lush string arrangements; a strong, contagious beat and thumping bass line; melodies melded from gospel, soul, and doo-wop; and accessible lyrics about family and survival.

Between 1971 and the early 1980s, the company produced more than 170 gold and platinum records with artists—a number of them also from Philadelphia—including the O’Jays, Wilson Pickett, Harold Melvin & the Bluenotes, Teddy Pendergass , Lou Rawls, and The Jacksons. Attracted by “The Sound of Philadelphia,” as it became known, artists from all over the world came to record at Sigma Sound, including Dusty Springfield, the Rolling Stones, David Bowie, and the Bee Gees. With studio time at Sigma becoming increasingly dear, Tarsia in 1974 rented space in the Gamble, Huff & Bell offices at 309 S. Broad Street, where they had moved from the Shubert Building the previous year. There, he built, equipped, and operated Sigma Sound South until 1988.

While Philadelphia International was thriving, the RCA Victor label struggled. RCA had been smart enough to sign Elvis Presley in 1955—he quickly became its biggest selling recording artist of all time—and the company continued to innovate, introducing the first stereo eight-track tape music in 1965 and the first quadraphonic eight-track tape cartridges in 1971. But as one unit in a large corporate conglomerate that focused its attention on larger, more profitable divisions, the once mighty RCA label floundered. After buying RCA in 1986, General Electric sold its interest in the RCA/Ariola International record label to Bertelsmann, then ceased manufacturing in Camden in 1992.

Philadelphia International Declines

By the late 1970s Philadelphia International Records was also in decline. After a plunge in record sales in the late 1970s and another shift in popular tastes, the company recorded fewer and fewer artists, then closed its doors in 2001. In the 1980s, however, the analog cassette recorder, affordable multi-track tape decks and mixers, and other emerging technologies enabled a new generation of small studios and independent producers to record and distribute their recordings.

One company that thrived was Philadelphia-based Disc-Makers, which began as a small recording studio and pressing plant in the 1940s, became a regional supplier of vinyl and cassettes for the recording industry in the Mid-Atlantic region by the 1970s, and then emerged as a leading digital optical disc manufacturer for independent artists, filmmakers, and businesses. In the early 1980s Disc Makers began to offer short-run vinyl pressing and cassette duplication to independent artists, including those in the emerging indie rock movement who were producing their own recordings, often in small, home studios. After the introduction of the Compact Disc (CD) in 1990, Disc Makers moved into short-run CD duplication, small batch CD-ROM packages for businesses, and then short run DVD replication. Having outgrown its Philadelphia location, Disc Makers in 1995 moved to a larger 82,000-square-foot facility in Pennsauken, New Jersey, where by 2010 it had produced more than 40,000 titles.

Market segmentation also gave rise to niche recording studios that catered to specific musical subcultures, and worked with local artists. Among these were Dreambox Media, a musicians’ co-op launched in 1986 that focused on recordings of Philadelphia jazz; Relapse Records, founded in Upper Darby in 1990, which diversified from underground “extreme metal” music into ambient, industrial, experimental, noise, and heavy rock; MilkBoy, founded in 1994 in North Philadelphia, which initially focused on punk and hip hop groups; and Dylanava Studios, set up in Gwynedd Valley in 1999. Close to New York City and offering high quality at comparatively low cost, Philadelphia recording studios attracted national and international artists, including native Philadelphians Will Smith and Jazzy Jeff, Boyz II Men, and other artists born and raised in the city.

The most successful of this next wave of Philadelphia recording studios was The Studio, founded by Larry Gold, a Curtis-trained classical cellist. Gold had been a member of Philadelphia International Records in-house band of studio musicians, MFSB (Mother Father Sister Brother), whose instrumental recordings included the 1974 number-one hit “TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia),” best known as the theme song for Soul Train, the long-running African-American musical variety television program. After Gold launched The Studio in the mid-1990s, it quickly became one of the best-equipped and most successful recording studios in the nation. Closely identified with neo-soul music, The Studio helped launch the careers of Jill Scott, Bilal, and other local artists, and became the home recording space for The Roots, another Philadelphia ensemble. Already established as one of the nation’s best studio musicians and string arrangers, Gold also worked at The Studio with Tori Amos, Erykah Badu, Mary J. Bilge, R. Kelly, Jennifer Lopez, Musiq, Justin Timberlake, and Kanye West.

Rise of Digital Technologies

The Studio opened just as emerging digital technologies were beginning to drive the next revolution in sound and moving image recording technologies, which were again transforming the recording industry. The digital revolution gave rise to unprecedented media convergence and a new wave of democratization far greater than that unleashed by analog tape, audio cassettes, and CDs, and other earlier technological innovations. It also forced Sigma Sound and other large, expensive recording studios to adopt new business models. Sigma, for example, retooled as a multi-purpose audio and video production complex that included a video studio and live performance space.

In the early 2000s, new studios emerged in Philadelphia and its greater metropolitan region that could produce sophisticated, multi-track, high fidelity recordings at lower and lower cost. More and more artists recorded entire albums on their laptop computers using inexpensive Digital Audio Workstations (DAWS) like GarageBand; released their music digitally on iTunes, YouTube, and other media players without physically pressing a disc of any kind; and sent media files via the Internet to multiple studios, whose physical locations were of less and less significance. Digital media raised exciting and perplexing questions about what new forms “canned music” would take and about how sounds and moving images could be captured, combined, marketed, disseminated, and experienced.

Charles Hardy III is a professor of history at West Chester University. Supervising historian of ExplorePAhistory.com, he is also the co-author, with David Goldenberg, of Philadelphia All the Time: Sounds of the Quaker City, 1896 to 1947 (Rydal, Pa.: Spinning Disc Productions, 1992). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Raising the bar on 'elevator music' (NewsWorks, March 21, 2014)

- RCA Victor-made 'race records' of '20s infuse new musical premiering in Camden (WHYY, October 16, 2014)

- Drexel students bring modern mixes to archive of funky recordings (WHYY, February 27, 2015)

- Students begin using recording studio donated by Drake (WHYY, March 10, 2015)

- Encore for iconic Camden recording company — with a new spin (WHYY, November 23, 2015)

- David Bowie's days amid the Young Americans in Philly (WHYY, January 11, 2016)

- Going on the record with process for pressing vinyl (WHYY, April 15, 2016)

- Record label debuts with compositions from Curtis (WHYY, August 22, 2016)