Philadelphia Stock Exchange

Essay

The Philadelphia Stock Exchange played an influential role in America’s financial and economic development. It helped the fledgling nation raise funds to develop infrastructure for a growing industrial base and new commercial banks and insurance companies. The Exchange is the nation’s oldest, founded two years before the New York Stock Exchange, and third-oldest globally, after the Amsterdam Exchange (1602) and Paris Bourse (1724). By 2015, it operated at the forefront of new technology accelerating accurate trading, providing better prices, and introducing new financial products.

The exchange originated in 1746 when Mayor James Hamilton (c. 1740-83) donated £150 in startup funds. Others followed his lead, but the funds went into constructing a new city hall. In 1754 Robert Morris (1734-1806) and local businessmen raised £348 to open the London Coffee House, which attracted merchants, slave traders, and enterprise owners.

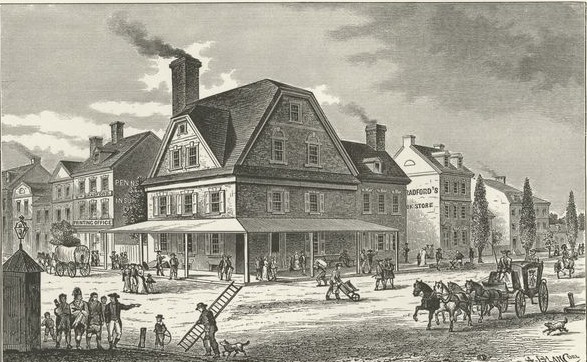

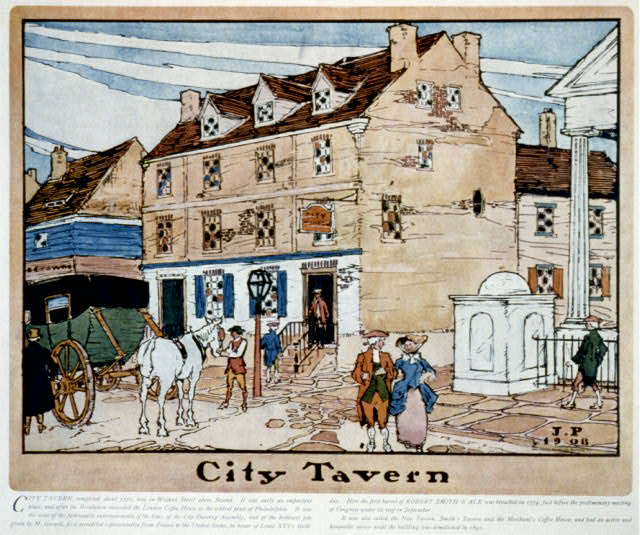

The Coffee House raised funds to help General George Washington fight the Revolutionary War. When the British occupied Philadelphia, the City Tavern replaced it as the business epicenter. The City Tavern, later named the Merchants Coffee House, became Philadelphia’s exchange.

As securities trading activity grew, investors established the Philadelphia Board of Brokers (1790), later becoming part of the exchange, focusing on government and semigovernment financial instruments, such as bonds, notes, and bills. In 1796, a more-restrictive exchange debuted, setting an entrance fee for brokers. This exchange raised money for necessary public works projects, including the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Company, America’s first turnpike, and the Lancaster and Susquehanna Turnpike. The exchange also handled bank and insurance stocks, permitting firms to acquire needed financial capital. These included The First Bank of the United States, the Pennsylvania Bank, and the Philadelphia Bank, as well as The Pennsylvania Company for Insurance on Lives and Granted Annuities, and The Insurance Company of North America.

When the War of 1812 disrupted American trade, the exchange helped the federal government raise capital for defense, and after 1815 became an important conduit for financial capital moving from Europe into America. Using these funds for construction, canals such as the Erie, the Chesapeake and Delaware, and the Susquehanna and Juniata helped extend the transportation grid. Soon, the exchange needed new facilities. In 1831, Philadelphia’s Stephen Girard (1750-1831) started the Philadelphia Merchants’ Exchange Company to build a new financial center. The Board of Brokers relocated there in 1834 after a fire at the Merchants Coffee House.

Even though the exchange’s securities activity grew, financial problems eventually erupted. Total debt for American infrastructure soared, yielding bond defaults by the issuing states and capital flight to Europe. Hammered by the Second Bank charter crisis President Andrew Jackson set in motion, the American economy collapsed in 1837. Only in the 1840s did the growth of railways spur the exchange’s recovery, featuring capital raised for the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Philadelphia Railway, and the Reading Railway. Meanwhile, Philadelphia’s first streetcar line, the Frankford and Southwark, proved so successful that investors funded fourteen other companies.

In addition, a new technology, the telegraph, helped securities trading intensify. Starting in 1846, telegraphy allowed investors quick access to stock quotes, news, and confirmed transactions helping to level the trading field. Within a decade, the exchange began issuing daily transaction reports; the Philadelphia Local Telegraph’s stock tickers arrived in 1873, providing real-time data. Three years earlier, Philadelphia’s exchange pioneered a clearinghouse system, facilitating the accurate settlement of securities sales, purchases, and deliveries. This permitted larger transactions and increased volume for the exchange, but with growth came more problems, notably repeated national panics and depressions. Surviving these, the exchange closed for four months in 1914 because of World War I market turmoil. It also closed during the 1933 Bank Holiday declared by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Nonetheless, the exchange thrived.

Following World War II, the exchange grew through mergers, first in 1949 with the Baltimore Exchange and in 1953 with the Washington (D.C.) Exchange. Acquisition of the Pittsburgh, Boston, and Montreal exchanges led to a new trading base called the Philadelphia-Baltimore-Washington Stock Exchange (PBW). In December 1968, the City of Philadelphia faced a fiscal crisis, resulting in a 5-cent-per-share stock-transfer tax imposed on every transaction. In reply, the exchange relocated its trading floor to Bala Cynwyd, just outside Philadelphia’s border. Three months later, a state court voided the tax and the exchange returned to Philadelphia.

In 1975, the exchange initiated electronic trading. The Philadelphia Automated Communication and Execution System computers interacted to provide instantaneous execution of security orders and more accurate price quotes than elsewhere. Furthermore, in the same year the exchange started listing stock options, the first regional exchange doing so. In 1976, its Board of Governors restored its original name, the Philadelphia Stock Exchange.

In April 1988, its Automated Options Market electronically delivered orders from member firms to the floor of the exchange and provided electronic confirmation of their execution. Exchange-traded currency options, introduced in 1982, yielded trading volumes eventually reaching $4 billion daily. Consequently, the exchange initiated evening trading sessions and, later, around-the-clock transactions.

The introduction of Sector Index Options in the 1990s, consisting of indexes such as the Gold/Silver Sector (XAU), KBW Bank Index (BKX), Utility Sector (UTY), and Insurance Index (KIX), allowed investors to use options trading for diverse industries and commodities. Further innovation occurred in the twenty-first century, as the exchange initiated Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs), combining the structure of a mutual fund with the possibility of transacting during the market day, not after its close. The exchange grew even more through the creation of UCOM (United Currency Options Market), which was the first financial market offering currency options customized for use in an exchange, including choice of exercise price, and expiration dates of up to two years.

In 2003, the exchange’s members voted to reorganize as a for-profit corporation, a major shift. This allowed it to become the first floor-based stock exchange converting from a member-owned institution to a shareholder-owned, for-profit corporation. This step led firms such as Citigroup, Credit Suisse, Morgan Stanley, and others to acquire nearly a 90 percent interest by 2005. The purchase allowed them a hedge against the increasing concentration of trading at the New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ. In a major move in 2006, the exchange halted the traditional floor trading that started in 1790.

A year later, NASDAQ OMX purchased the exchange for $652 million in order to diversify by acquiring an options platform. This resulted in its becoming the largest electronic stock market, listing over 3,000 firms, and the third largest options market domestically. In 2014, the exchange handled approximately 14 percent of derivative trades in the United States, chiefly stock, currency, and index options, using an advanced trading system that set new technological standards.

Arthur S. Guarino is an Assistant Finance Professor at the Rutgers University Business School teaching courses in Financial Institutions and Markets, Corporate Finance, Financial Statement Analysis, and Financial Management. He has published articles dealing with economic history and the role of finance and economics in public policy.

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University