Philadelphia Ten

By Page Talbott

Essay

When an exhibition of 247 paintings opened on February 17, 1917, at the Art Club of Philadelphia, 220 S. Broad Street, it heralded the birth of the Philadelphia Ten (also known as The Ten), an evolving all-women’s group of painters and sculptors that exhibited together for nearly thirty years. Soon their exhibitions became an annual event that critics and collectors could depend upon for consistently high quality and a variety of subject matter and styles. Because of the large number of works by each artist on view, critics came to recognize their individual work and the gender-specificity of their art. While this artist group did not become particularly well known outside of art circles, its work sold well and in many cases provided a good living for the artists. Some of these artists, notably painters Theresa Bernstein (1890–2002), Fern Coppedge (1883–1951), and M. Elizabeth Price (1877–1965), and sculptors Beatrice Fenton (1887–1983) and Harriet Frishmuth (1880–1980), garnered considerable fame, big prices on the American art market, and representation in the collections of major museums.

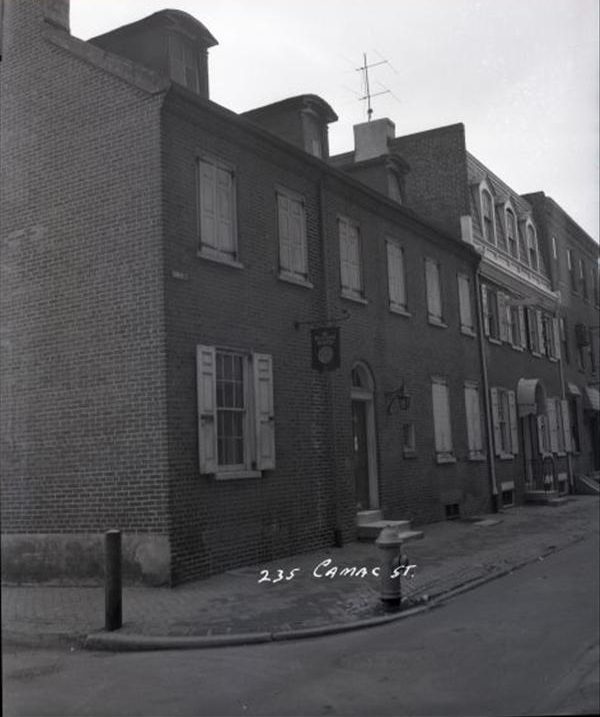

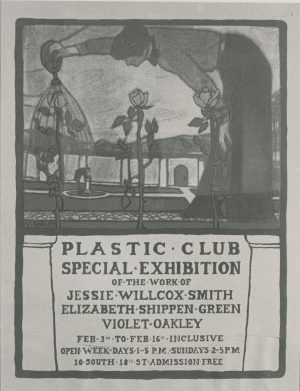

Local and regionally-based art clubs proliferated during the opening decades of the twentieth century, and women’s art organizations such as the Plastic Club at 247 S. Camac Street in Philadelphia and the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors in New York City sponsored exhibitions beginning in the late nineteenth century. Most of these artists had previously participated in group exhibitions; several had shown work in the annual “Exhibitions of Works in Oils” begun at the Art Club in 1913.

What distinguished the 1917 exhibition was that all the participants had been trained in the art schools of Philadelphia—nine at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women housed in the Edwin Forrest Mansion at 1326 N. Broad Street (later Moore College of Art and Design) and two at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts at Broad and Cherry Streets. Furthermore, the number of exhibitors was limited to a relatively small group of artists who wanted to exhibit many works at one time in a situation they could control for design and content. Significantly, the Philadelphia Ten exhibited longer and more widely than any other all-women’s American artist group.

Landscapes always predominated in exhibitions of the Philadelphia Ten, as they did in the Philadelphia School of Design for Women’s painting program, although still-lifes and portraits also were regularly represented. The choice of subject matter of graduates of the School of Design for Women, in general, and the Philadelphia Ten, in particular, also related to another common theme of art reviews during the first half of the twentieth century—the issue of gender as reflected in a painter’s output, particularly if the artist was female. Contemporary reviews debated the “feminine” nature of their work, implying the genetic ability of women to generate works of beauty and to choose subjects that were beautiful.

Opportunities for Female Artists

While the issue of masculine versus feminine styles may have been on the minds of those who reviewed art exhibitions of the period, for the women of the Philadelphia Ten this conversation may have seemed irrelevant. For them, art provided a means of financial support and creative expression. Primarily from an upper-middle-class background and educated in the best art schools, these women achieved economic independence and professional success in a field where neither was assured. The impact of a career on the personal lives of these thirty women seemed to mimic the experience of others of their era who chose a professional career over the more traditional role of full-time wife and mother. Since most of the Philadelphia Ten were educated before 1910, they represented the first generation of modern art professionals, some of whom felt compelled to choose art over a commitment to home and family.

Five women participated in all or most of The Ten’s exhibitions: Isabel Branson Cartwight (1883–1966), Constance Cochrane (1885–1962), Mary Russell Farrell Colton (1889–1971), Edith Lucile Howard (Roberts) (1885–1960), and M. Elizabeth Price. Additional stalwarts were Theresa Bernstein, Fern Isabel Coppedge, and Nancy Maybin Ferguson (1872–1967). The subjects of these artists’ work ranged from still-lifes, to portraits, to landscapes, which were painted throughout the country and the world. Coppedge, however, largely painted scenes from the Lambertville/New Hope area of Bucks County; M. Elizabeth Price chose subjects she could see from her front yard on the Delaware River in Solebury, Pennsylvania; and Ferguson painted views of Rittenhouse Square and Fairmount Park.

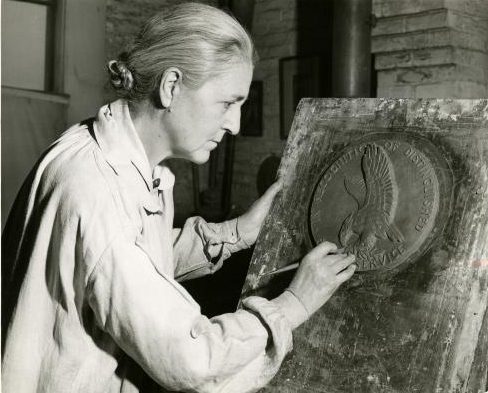

A handful of exhibitors died young. Helen Kiner McCarthy (1884–1927), Cora Smalley Brooks (1885–1930), Elizabeth Wentworth Roberts (1871–1927), Suzette Schultz Keast (1892–1932), and Marian T. MacIntosh (1869–1936) all died in their fifties or earlier. By contrast, in addition to Theresa Bernstein who died at 111 and Harriet Frishmuth at 100, a surprisingly large number of these women survived well into their nineties and beyond: Sue May Gill (1887-1989), Katharine Marie Barker (Fussell) (1890–1984), Arrah Lee Gaul (Brennan) (1888–1980), Edith Longstreth Wood (1871–1967), and Emma Fordyce MacRae (Swift) (1887–1974). Other painting members included Susan Gertrude Schell (1891–1970), Eleanor Abrams (1885–1967), Maude Drein Bryant (1880–1946), Margaret Ralston Gest (1900–1965), and Katharine Hood McCormick (1882–1960). Beginning in 1926, seven sculptors also exhibited with the Philadelphia Ten: Gladys Edgerly Bates (1896-2003), Cornelia Van Auken Chapin (1893–1972), Beatrice Fenton, Harriet Whitney Frishmuth, Genevieve Karr Hamlin (1896–1989), Joan Hartley (1892-–1984), and Mary Louise Lawser (1906–1983). Sue May Gill occasionally exhibited sculpture as well. While the work of these seven sculptors varied in style, their oeuvre was primarily traditional and figural, with an emphasis on garden sculpture and fountains. Fenton’s work can be widely seen in various public spaces in Philadelphia, including the Evelyn Taylor Price memorial sundial in Rittenhouse Square and Pan with Sundial on Woodland Walk on the University of Pennsylvania campus.

Financial Success

Instant recognition by style was an ongoing goal of members of the group, self-supporting entrepreneurs for whom sales were critical. Vigorous self-promotion, aggressive marketing, and creative outreach all contributed to their commercial success. Paintings at the Philadelphia Ten’s exhibitions were always for sale, apart from a small number of loans, and prices ranged from $50 to $1,000, with an average of $350 to $500. One facet of The Ten’s marketing strategy coincided with their zealous belief in art education, their interest in bringing the fine arts to a broader segment of the American population, and the desire to encourage women to explore their innate artistic talents. In the 1920s and 1930s the Philadelphia Ten circulated “Rotary” exhibitions that traveled under the auspices of two important, yet divergent, organizations: the State Federation of Pennsylvania Women, a branch of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, which circulated exhibits to its member clubhouses in communities around the state, and the American Federation of the Arts, established in 1909 to send exhibitions of original works of art to the “hinterlands,” sponsored The Ten’s exhibits throughout the United States.

The remarkable stability of the Philadelphia Ten, despite changes in membership, was noteworthy considering the political, economic, and social upheaval that occurred during the nearly thirty years of the group’s active existence. World War I, the stock market crash of 1929 and the subsequent Depression, and World War II were the historical realities of this period. While each of these major events had a profound impact on the individual lives as well as the collective story of these women, they nonetheless continued to produce and sell their art. Their final exhibition took place at the Woodmere Gallery on Germantown Avenue in Chestnut Hill in April 1945. The Woodmere subsequently purchased several works by members of The Ten, including Bernstein, Cochrane, Coppedge, Ferguson, Fussell, Gill, McCormick, and Schell.

In 1924, Public Ledger art critic Arline De Haas (1899–1969) wrote that the names of the Philadelphia Ten painters “stand out as among the foremost women in their line of expression and each one has so created her own atmosphere that her work is suggested with the mention of her name.” Neither avant-garde nor feminist, the exhibitions of The Ten were nonetheless an important vehicle for bringing high quality art work done by women to the attention of the public. As such they represented an important step towards the fuller participation of women in the broader art community.

Page Talbott is Principal, Talbott Exhibits and Planning, and until July 2016 was president and CEO of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. During her fifteen years as consulting curator for Moore College of Art and Design, she studied and wrote about the artists of the Philadelphia Ten, many of whom attended the school when it was known as the Philadelphia School of Design. Among her many publications are The Philadelphia Ten: A Women’s Artist Group, 1917-1945, with Patricia Tanis Sydney, and Benjamin Franklin: In Search of a Better World (Yale University Press, 2005).

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- The Art Club of Philadelphia (The PhillyHistory Blog)

- The Plastic Club

- National Association of Women Artists, Inc.

- Moore College of Art & Design

- Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

- Evelyn Taylor Price Memorial Sundial (1947) by Beatrice Fenton (Philadelphia Association for Public Art)

- American Federation of Arts

- Woodmere Art Museum